DUBAI: Sudan’s military reinstated Abdalla Hamdok as prime minister of the country’s civilian transitional government on Nov. 21 and pledged to release political prisoners following weeks of deadly unrest in the wake of the October coup.

However, the new power-sharing arrangement appears far from secure amid continued protests by Sudanese pro-democracy groups against the military’s involvement in the government.

After being held under house arrest since Oct. 25, Hamdok was reinstated upon signing a 14-point agreement with coup leader Gen. Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan during a ceremony broadcast on state television on Sunday.

“The signing of this deal opens the door wide enough to address all the challenges of the transitional period,” Hamdok said during the ceremony.

“Sudanese blood is precious. Let us stop the bloodshed, and direct the youth’s energy into building and development,” he added, according to Reuters news agency.

Now that he has returned to office, Hamdok will lead an independent technocratic Cabinet until new elections are held before July 2023. However, it remains unclear how much real power the civilian government will wield under the military’s oversight.

Amani Al-Taweel, a researcher and expert on Sudanese affairs at Cairo’s Al-Ahram Strategic and Political Studies Center, believes the agreement’s effectiveness will depend largely on public acceptance of its legitimacy.

“This is a matter that depends on the extent to which the street and the people accept the agreement that was signed,” she told Arab News.

“If it is accepted, we will reach a safe end to the transitional period, and if not, the situation will become more complex and open to security threats.”

Many political groups have no confidence in Hamdok’s professions of faith in the deal and accuse him of selling out the revolution.

Sudan's Prime Minister Abdalla Hamdok chairs an emergency cabinet session in the capital Khartoum. (AFP)

The Sudanese Professionals’ Association, one of the key players in the uprising against former leader Omar Al-Bashir, strongly opposes the agreement and says Hamdok has committed “political suicide.”

“This agreement only concerns its signatories, and is an unjust attempt to bestow legitimacy on the latest coup and the military council,” the group tweeted after the signing ceremony.

The Forces for the Declaration of Freedom and Change, a group made up of several political parties and pro-democracy groups, has also objected to any new political partnership with the military and insists the perpetrators should face justice.

“We totally reject the treacherous agreement signed between Hamdok and Al-Burhan, which concerns only its signatories,” it said in a Facebook statement. “The points of the subservience agreement are far from the aspirations of our people and are nothing more than ink on paper.”

The Umma Party, Sudan’s biggest political bloc, has also issued a statement implying it does not support the deal, AP reports.

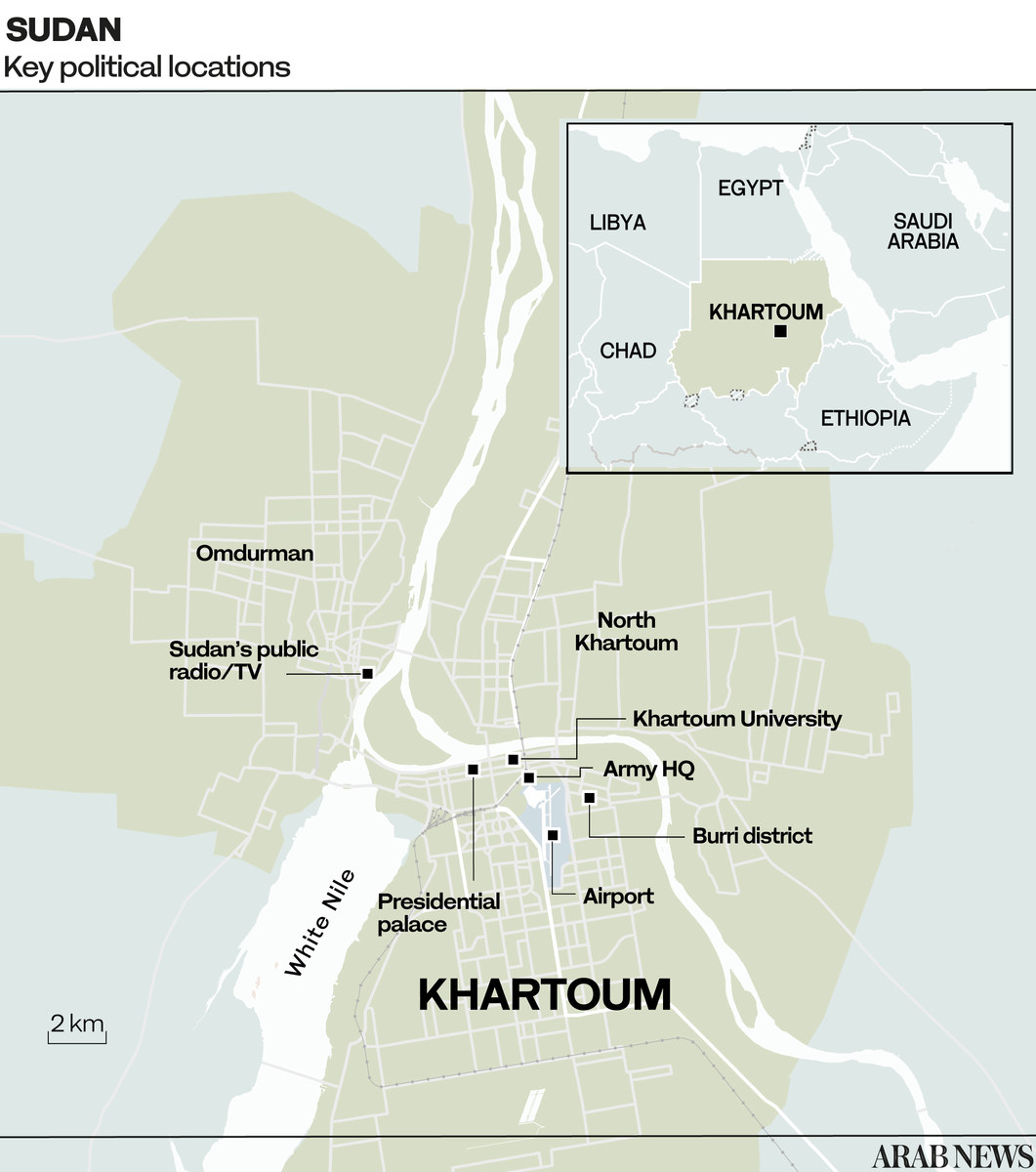

Meanwhile, protesters have rallied in the capital Khartoum, Omdurman and Bahri, chanting “No to military power” and demanding a full withdrawal of the armed forces from the government.

According to Zouhir Al-Shimale, head of research at Valent Projects, there are two likely scenarios, both of which depend on what Hamdok chooses to do next.

“In one, Hamdok will play a positive role by supporting the demands for democracy, justice and peace of the Sudanese revolution,” he told Arab News.

“In the other scenario, he will ostensibly back the street’s demands but, in actual fact, legitimize and support the October coup leaders, and act as their international political front.”

Hamdok, 65, has been the face of the country’s fragile transition to civilian rule since the 2019 overthrow of Sudan’s long-time leader Al-Bashir.

The British-educated economist, who was previously deputy executive secretary of the UN Economic Commission for Africa, had developed a reputation as a champion of good governance and transparency.

A woman speaks during the funeral procession for a Sudanese protester in the capital Khartoum. (AFP)

Although he did not take part in the 2019 revolution, he was widely seen as the ideal candidate to help steer Sudan’s democratic transition.

His government inherited a country long squeezed by US sanctions, wracked by economic crisis, suffering shortages of basic commodities, and with a banking sector on the brink of collapse.

Since its independence was recognized in 1956, Sudan has been plagued by internal strife and political instability. The secession of South Sudan in 2011 delivered multiple shocks to the economy following the loss of valuable oil revenues.

The consequent slowdown in growth and double-digit consumer price inflation triggered protests among a population increasing at a rate of 2.42 percent per year.

Sanctions were lifted soon after Hamdok joined a transitional government in August 2019 and Sudan was subsequently removed from the US Treasury’s list of state sponsors of terrorism.

Since then, however, the country has been beset by daunting socioeconomic problems, made worse by the global pandemic.

Sudan's top army general Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan speaks during a press conference at the General Command of the Armed Forces in Khartoum. (AFP/File Photo)

In the face of these overlapping crises, army chief Al-Burhan announced a state of emergency on Oct. 25, deposing Hamdok and arresting several members of the transitional government.

The international community condemned the move and suspended much-needed economic assistance to Sudan. The World Bank froze aid and the African Union suspended the country’s membership.

Under the circumstances, the Nov. 21 deal has been largely welcomed by the international community, which views it as a first step toward getting Sudan’s fragile transition process back on track.

The US, Britain, Norway, the EU, Canada and Switzerland all welcomed Hamdok’s reinstatement and, in a joint statement, urged the release of other political detainees. The Saudi foreign ministry has said the Kingdom supports everything that will achieve peace and maintain security, stability and development in Sudan.

Some political observers believe the coup was simply a crude attempt by the Bashir-era old guard to retake power.

People take part in a funeral procession for a Sudanese protester in the capital Khartoum. (AFP)

“Sudan reached this point due to a post-revolution political dilemma and stalling by members of the Sudanese army, who are the remnants of the pro-Bashir regime and Muslim Brotherhood figures, the Rapid Response Forces, as well as some regional actors,” Al-Shimale told Arab News.

“They have been collectively undermining the post-revolution progress, namely the civilian-led transitional government.”

The October coup triggered weeks of demonstrations across Sudan, in which at least 41 people were killed, according to medical sources. The Nov. 21 agreement sets out plans for a thorough investigation into the killings.

Al-Shimale believes the Sudanese people are divided over the agreement because many of its clauses have not been made public. “The deal has already affected Hamdok’s image among Sudanese both inside and outside the country,” he told Arab News.

“They are arguing that the PM’s deal with the coup leaders is like a stab in the back for those who believed that he supported the civil right movement. However, others are considering his stance as a political maneuver and not a submission to Al-Burhan’s demands nor legitimizing his coup.”

Hamdok faces considerable challenges, in addition to the risk of reputational damage.

Sudanese security forces shot at protesters on November 13 in a crackdown on anti-coup demonstrations, medics said, after the military tightened its grip by forming a new ruling council. (AFP)

Before the coup, in order to secure international funding, his government implemented a number of austerity measures, including the removal of subsidies on petrol and diesel, and the floating of the Sudanese pound.

Many Sudanese believe the steps were too harsh and overly hasty. In mid-September, anti-government protesters responded by blockading the country’s main sea port, triggering nationwide shortages of wheat and fuel.

Hamdok’s government was also accused of failing to deliver timely justice to the families of those killed under Al-Bashir, including those who died during the 2018-19 protests, leaving him vulnerable to criticism.

“The situation facing Sudan after the latest deal is too complicated to predict,” Al-Shimale said. “On the political front, Sudan has entered another era of uncertainty and it will take a long time for the new government to come to grips with the business in hand.”

He added: “Local resistance coordination groups will continue protesting Hamdok’s partnership with the military, and political order won’t be restored unless Hamdok succeeds in crafting a new political dynamic under which a civilian-led — not military-headed — Sudan will be able to address the revolution’s demands.”