DUBAI: As the countdown begins to Iraq’s parliamentary elections on Oct. 10, some political parties are hoping that the voting-age population will overlook their history of broken promises and succumb to their blandishments. The onus is on the 25 million voters on Iraq’s electoral roll to choose their representatives wisely if they want to see different results this time around.

That message is being hammered home by Mustafa Al-Kadhimi, Iraq’s prime minister, via tweets and public statements, concurrently with appeals to voters to turn out in large numbers on election day. “Our dear Iraqi people. For the sake of yours & your children’s future, I urge you to get your voter registration cards,” he said in a tweet on Sunday.

“Your votes are a responsibility that shouldn’t go to waste. Those wanting reform & change should aim for a high voter turnout. Your votes are the future of Iraq.”

In a tweet on Sept. 24, Al-Kadhimi called on Iraqis to cast their ballots judiciously so that mistakes of the past are not repeated. “Don’t trust fake promises, and don’t listen to threats and intimidation,” he said. “Defeat them with your votes, in free and fair elections. Together we move forward towards a future that Iraqis deserve.”

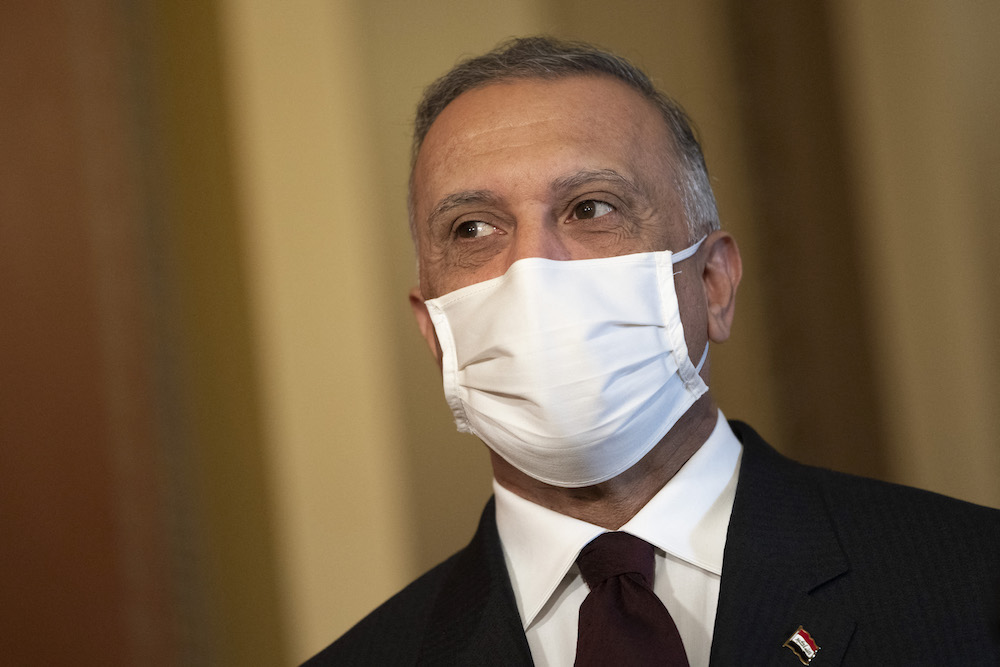

Al-Kadhimi listens as US President Joe Biden speaks during a bilateral meeting in the Oval Office at the White House on July 26, 2021. (AFP/File Photo)

Few Iraqis could have known better than Al-Kadhimi how slim the chances were, until now, of major change occurring through the ballot box. Following the re-introduction of parliamentary elections in 2005, Iraqis did not vote for individual candidates, but for patronage-friendly lists — or tickets — that competed for the seats in each of the 18 provinces.

With the adoption of a new electoral law last year that divides the country into constituencies, independent candidates now have an opportunity to compete for the 329 parliamentary seats. That being said, the electoral system has bred deep disillusionment with a political class that has proved either incapable or unwilling to provide security and good governance, fix the economy and heal sectarian and religious divisions.

“Although Iraq’s political elites have shown little willingness to change, some acknowledge that opening the political field for reform may be the only way to prevent another mass outburst, whose consequences could be far more damaging,” Lahib Higel, a senior Iraq analyst for the Crisis Group, said on Twitter.

She added: “In order to restore public confidence in the short term, the government must facilitate a safe environment for elections, where new political actors can compete without fear of losing their lives.”

In a tweet on Sept. 24, Al-Kadhimi called on Iraqis to cast their ballots wisely so that costly mistakes of the past are not repeated. (AFP/File Photo)

Before Al-Kadhimi, five politicians had held the prime minister’s office in Baghdad since 2005, but none of them was able to make progress in ending corruption, raising living standards, creating jobs and opportunities for young people, or providing security.

Admittedly, not all the failures can be chalked up to individual incompetence.

Iraq’s sectarian power-sharing system has stood in the way of the political reforms demanded by protesters who took to the streets of Baghdad in October 2019. Although assassinations and the pandemic put a damper on the protests, parties from across the ethno-sectarian spectrum continued to be viewed as only interested in keeping their positions of power.

Since the beginning of 2020, COVID-19 has infected over 2 million Iraqis, leaving more than 22,000 of them dead, according to Worldometer data. The rapid spread of the disease has put tremendous strain on Iraq’s battered healthcare system.

Al-Kadhimi (R) receiving Dubai's Ruler and UAE Vice President Mohammed bin Rashid Al-Maktoum (L), upon his arrival at the airport in the capital Baghdad. (AFP/File Photo)

Falling oil prices in 2020 caused by the pandemic upended Iraq’s budget, which remains heavily dependent on crude exports. On top of everything, the leadership has had to face challenges in the form of paramilitary groups, remnants of Daesh and violations of Iraq’s territorial integrity by neighboring states.

Clearly, the task of restoring hope remains as daunting as ever, but as long as Al-Kadhimi is in charge, Iraqis at least have reason not to despair. On his watch, a key demand of the anti-government protesters who took to the streets in 2019 — that the government bring forward elections originally scheduled for May 2022 — has been met.

In foreign policy, one of the biggest successes has been the Baghdad Conference for Cooperation and Partnership of Aug. 28. It was attended by high-level delegations from France, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Iran, Turkey, Egypt, Qatar and the UAE in addition to the general secretaries of the Arab League, the Gulf Cooperation Council and the Organization for Islamic Cooperation.

That the Iraqi prime minister managed to bring so many heads of governments and organizations under one roof, even if for only one day, was undoubtedly a major achievement. The assurance of support from the international community that Al-Kadhimi evidently enjoys will probably continue to be his strong suit going forward.

Being seen as a rare safe pair of hands means that friends of Iraq, mindful of the competing interests that Al-Kadhimi has to juggle, are willing to cut him some slack, particularly in how he deals with the security and administrative challenges posed by the country’s unruly Shiite militias.

Being seen as a rare safe pair of hands means that friends of Iraq, mindful of the competing interests that Al-Kadhimi has to juggle, are willing to cut him some slack. (AFP/File Photo)

If Al-Kadhimi returns as prime minister after the October elections, analysts believe the government is likely to stick to the current non-sectarian tack.

“His performance so far has proved that he is capable of doing it. Among the political figures who have tried it so far, Al-Kadhimi has demonstrated the most dexterity,” wrote Yasar Yakis, a former foreign minister of Turkey, in an op-ed this week for Arab News.

For his part, Al-Kadhimi, aware of the many political constraints of his job, has been reminding his compatriots that they have to do their bit too if they want a brighter future.

“Protecting our nation and upholding our integrity can’t be achieved by turning a blind eye to errors,” he said via Twitter on Tuesday. “The Iraqi people upheld the values of justice, tolerance and sacrifice throughout history. They deserve a dignified life in the democracy they have chosen.”

It has been said that democracy is the worst form of government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time. That old dictum is a reminder of the slight comparative advantage that Iraqis have in spite of all the hardships they face.