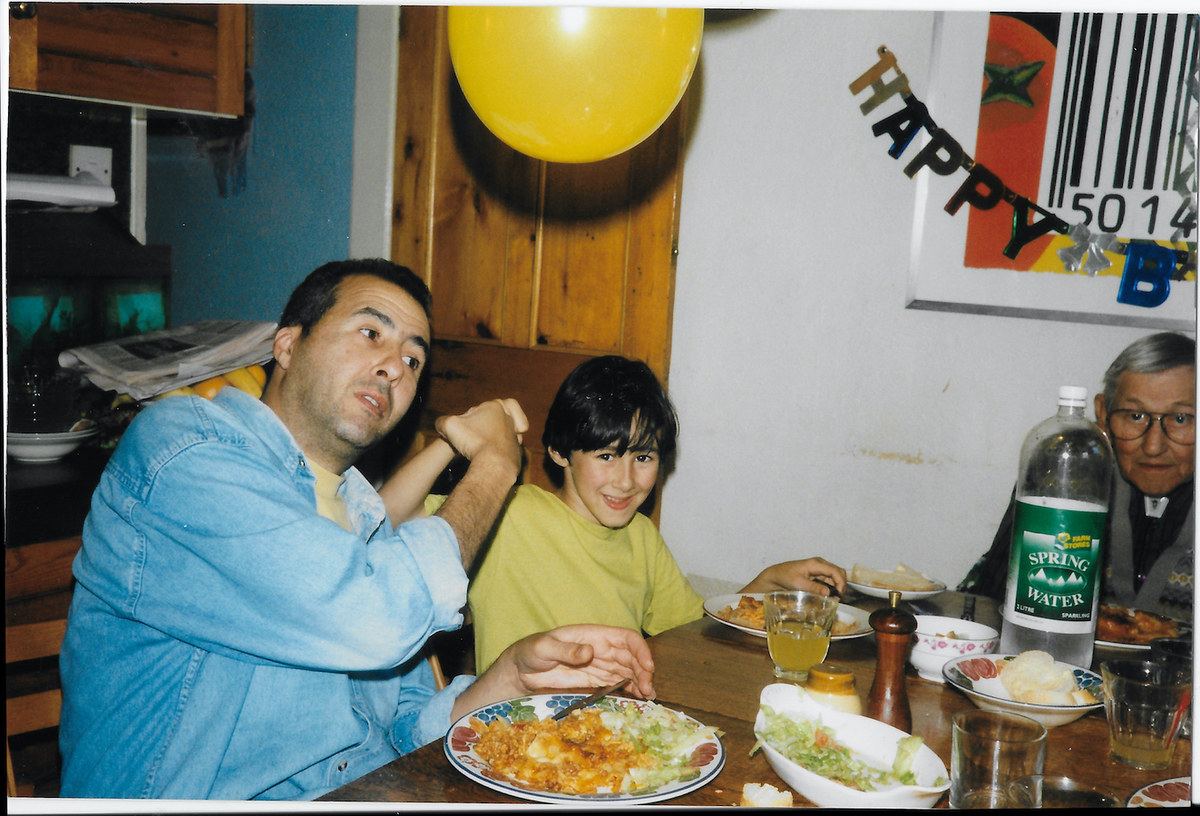

LONDON: “It almost felt like a necessity,” says Sherif Dhaimish, the son of Libyan artist and satirist Hasan ‘Al-Satoor’ Dhaimish. “I had to do this. Something had to be done because if I didn’t, nobody else would. And I’m not saying that in the sense it’s a burden to me — if anything I’ve found it quite cathartic. I think it’s helped me with the grieving process.”

Dhaimish, a publisher and curator based in Southeast London, is sitting in a café near Waterloo station, quietly but passionately discussing the life and work of his late father. “We were very close, we were really good mates, and when he passed away in 2016 it was hard, you know? For a short while, confronting his work was really difficult. But the more I’ve done it the closer I feel to him and I feel privileged that he’s left behind such work.”

Hasan working at his home in Burnley, Lancashire, 1980. (Supplied)

Hasan spent the majority of his life in exile in the Northwest of England. He waited tables in an Italian restaurant, attended music festivals, and lived a modest life with his wife and three children. Now his journey from penniless young émigré to satirical giant is being brought vividly to life in “Resistance, Rebellion, Revolution - A Libyan Artist in Exile.”

Taking place at London’s Hoxton 253 and co-curated by Dhaimish’s sister Hanna, the exhibition coincides with the 10-year anniversary of the Libyan revolution and is a ‘ruminative reflection on the artist’s life in exile.’

“The fact that I’m able to do a show here in London and generate some interest — for me that’s a win,” says Dhaimish. “I haven’t really got a game plan in terms of how big I want to make this. I just know that from speaking to people over the past few years — from academics to journalists, to former friends of my dad, to human rights activists and people who work in the art world — he’s got a very unique story and one that a lot of people can relate to. There’s the exile, the politics, the music, and yet he was very humble about his work.”

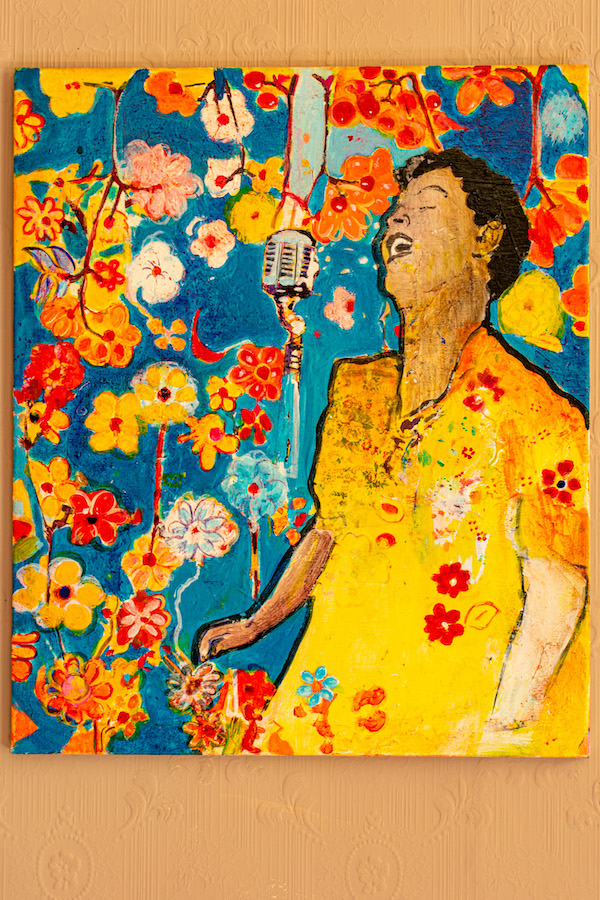

Billie Holiday, 2009. (Supplied)

Hasan’s father, Sheikh Mahmoud Dhaimish, had been a religious adviser to King Idris, who was deposed in a coup d’état led by Muammar Qaddafi in 1969. Hasan originally arrived in England aged 19, and with no intention of staying, but the political situation back home led to his father’s recommendation that he remain abroad until Qaddafi was gone. As months turned into years, he eventually settled near Burnley in Lancashire, married Karen Waddington, and became heavily involved in the Libyan opposition movement.

His involvement in the latter was initially triggered by a trip to London in 1979, when he spotted a distinctive orange-colored magazine on an Arabic newsstand outside Earl’s Court tube station. Published by the Libyan opposition, it was called ‘Al-Jihad’ and would become the platform through which his "rhythmically witty, acerbically insightful, and playfully relentless” political satire would reach the world. He adopted the moniker Al-Satoor (The Cleaver), exposed the regime’s widespread corruption and injustice, and mercilessly lampooned Qaddafi.

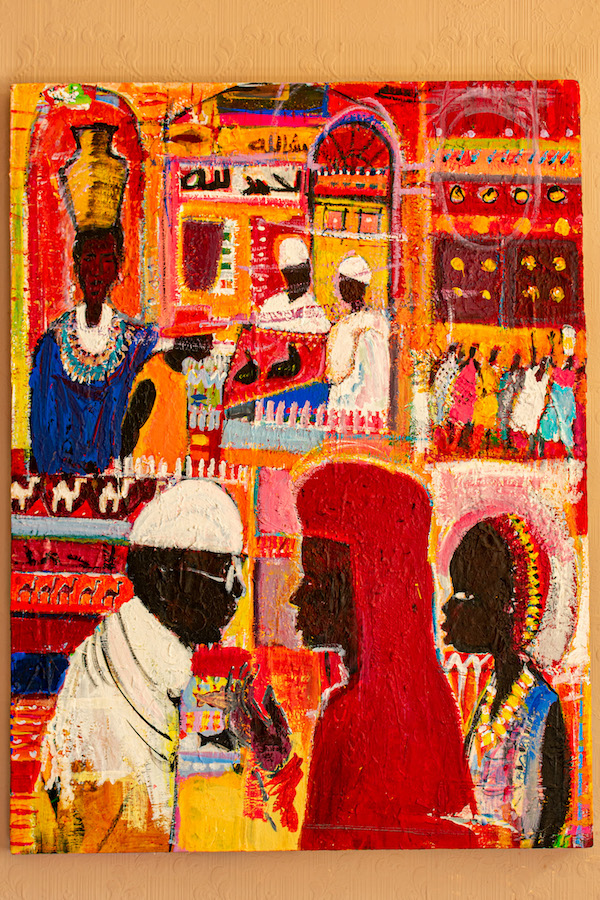

Medina, 2010. (Supplied)

But there was another side to Hasan. A great lover of music, he painted to the sounds of Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk and Blind Willie Johnson and brought jazz and blues to life through his work. It is this artwork that is arguably at the heart of “Resistance, Rebellion, Revolution,” which examines how the artist expressed himself outside of the highly fractious world of political activism.

“He often spoke of his political work as a necessity, and obviously it was something he cared deeply about, but he also saw the political arena for what it was,” says Dhaimish. “He urged me to stay away from that. But when he was producing his art he didn’t do that for anyone else but himself. It was therapy in a way and I think it was a good coping mechanism for him. He was very unorthodox in everything he did, so for me it’s important to try and tell his story in a way that doesn’t pigeonhole him as a Libyan satirist.”

With no previous formal education, Hasan’s artistic journey began in the late Eighties when he enrolled on a computer course at Nelson & Colne College. Uninterested in word processing, he began to dabble with the paint brush tool instead and was encouraged to pursue art by one of the teachers.

A memorial was constructed near the courthouse in downtown Benghazi where pictures of people who sacrificed their lives for the revolution were displayed. (Supplied)

“It unshackled him from the caricature and he started to become more artistically aware,” says Dhaimish. “He did his A Levels, went to university in Bradford, and then came back and became a teacher at the same college. So a big part of the exhibition is showing the art that he produced outside of the satire.”

Dhaimish has taken a sample of his father’s work and presented it in a way that narrates what was happening in Libya at the time. There’s a selection of cartoons from 1980 to 2016, a series of canvases, prints and photographs, and a six-minute biographical video. There’s also an accompanying online archive and a limited-edition book, all of which is supported by Pendle Press and Arts Council England. It is the first time that Hasan’s work has been shown in London, although a previous exhibition was held in Pendle in Lancashire in 2018.

Hasan and his son Sherif in London, 1995. (Supplied)

The process of putting the show together has been a labor of love, but also a hugely time-consuming project. The gathering of his father’s work has been a mammoth undertaking (to date there are 7,000 cartoons in the archive), while COVID-19 and other challenges have led to venue, date and budget changes. Dhaimish has also had to choose what to present and what to omit, and to understand that he is, after all, his father’s son. The latter has meant that there was always going to be a certain way he told his father’s story.

“There’s the personal side of all of this but on the other side there’s the freedom of thought that he represents,” says Dhaimish. “In a world where things are very polarized in some ways — you’re either on one side or the other — sometimes people like my dad, who was floating around creatively and was hard to pin down, represented something different. He was a bit of an anomaly, but these sorts of narratives are super-important to tell.”

The reasons why they are important, and what he believes his father’s legacy is, is something Dhaimish has thought long and hard about. “If there’s one overarching thing that people can take away — whether you agree with his political work or not, or whether you like his artwork or not — he was a critical thinker and he was an independent thinker. And that’s what he promoted. That was his thing. He didn’t care if people agreed with him or not. What he wanted people to do was to see things from a different angle,” he says. “That, for me, is the most important thing. You could speak to any of his former students and that was the one thing he taught them to do: Think for yourself.”