RIYADH: Saudi Arabia’s role in the global push for a more sustainable future is perhaps most vividly illustrated by “Green Riyadh” — a focal point of the Saudi Green Initiative. From having one of the lowest proportions of green space per capita of any major city, the capital will soon emerge as a lush urban habitat.

Official statements have said the greening of Riyadh “will significantly improve the lives of its citizens, transform the city into an attractive destination and make it one of the world’s most livable cities.”

This is not the first time Riyadh has undergone a metamorphosis, and it is unlikely to be the last. The story of Riyadh is one of evolution, with each new chapter reflecting a shift in the wider culture and fortunes of Saudi Arabia.

Riyadh, which translates as “the gardens,” was an unlikely name for this mostly dun-colored city situated in the middle of the bone-dry Nafud desert. The description goes back to the 14th century, when the city (then called Hajr) was depicted by famed Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta as “a city of canals and trees.” No trace remains of that legendary “Venice of the desert.”

Picture dated 1937 shows the historic wall of Riyadh city, which was declared by King Abdel Aziz bin Saud (1932-53) as the capital of Saudi Arabia in the early 1930s. (AFP/File Photo)

The Riyadh we know today emerged in the mid-18th century, when the local ruler Deham Ibn Dawwas built a wall around the dense, one-square-kilometer conurbation of mud-and-wattle houses and narrow alleyways. This traditional, vernacular avatar of Riyadh was still largely intact when King Abdul Aziz founded the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia in 1932.

Until the 1950s, Makkah was the focal point of Saudi Arabia and the seat of its government. Envisioning Riyadh as the capital of a more modern and integrated country, King Saud made the bold decision to relocate his entire government. The new neighborhood of Malaz was purpose-built to contain all state ministries in addition to modern housing, commercial and educational facilities.

The burgeoning oil sector of the 1960s and 1970s was the catalyst for another re-imagining of Riyadh as a car-based city.

King Faisal invited the Greek urban planner Constantinos Doxiadis to oversee the design of a “supergrid,” whereby Riyadh was neatly intersected by throughways along the lines of Dallas or Phoenix in the US.

As a key element of Vision 2030, the government is investing no less than SR 80 billion in Green Riyadh to improve its environment. (Supplied/Green Riyadh)

The Doxiadis masterplan stated that the new urban pattern “should be adapted to dynamic growth, with a central spine allowing the city to grow (in line with) its population.”

A modern city took a while to materialize, however, and the gigantic empty lots created by the grid were only gradually filled — a process that continues to this day. It is easy to forget that the trendy new hotspots of U-Walk, The Boulevard and Riyadh Front were dusty wastelands only a few years ago.

The emerging car-based metropolis provided order and efficiency and catered to a steadily growing population of locals and compound-dwelling expats. But the lack of pavements and overpasses proved a challenge for pedestrians, and, with few public transport options, Riyadh became a difficult place to live for those without a car.

The 1990s introduced a whole new dimension to the rapid growth of Riyadh: From horizontal to vertical. The Faisaliyah Center was the city’s first true skyscraper and very much the shape of things to come. Designed in 1994 by the UK’s Foster & Partners, the complex — unusual for its external superstructure and pointed apex — was unveiled six years later with its 30 floors of office space, three-story mall, globe-shaped restaurant, and observation deck with 360-degree views of the surrounding city.

Inaugurating his “Eiffel Tower of Riyadh,” Norman Foster said he “wanted a concept that was not only original but one that the community would be proud of in years to come.”

Soon to follow in 2002 was the Kingdom Center — an SR 2 billion ($533.33 million) project and definitive landmark. Winner of the 2002 Emporis Skyscraper Award, the 99-story building has a more streamlined and elegant design than the Faisaliyah Center, a unique feature being its Sky-Bridge walkway.

Riyadh’s next big vertical development was the King Abdullah Financial City, imagined as a regional banking and finance hub to rival London’s Canary Wharf. This cluster of high-rise towers has radically altered the skyline.

By 2005, Riyadh was taking its place as a global city. But however dramatic Riyadh’s physical changes appeared, the virtual impact has arguably been more profound. With the growing ubiquity of smartphones, the Saudi capital quickly became known as a “smart city,” where every citizen has 24/7 online access to a full range of services.

The Lausanne-based Institute for Management Development’s 2020 Smart City Index ranked Riyadh “ahead of Tokyo, Rome, Paris and Beijing in terms of digital connectivity to healthcare, mobility, leisure activities and governance.”

The inaugural celebration of Diriyah Gate. (Supplied)

This tech prowess came into its own during the coronavirus disease pandemic, when the Kingdom’s ministries of interior and health quickly developed apps to provide support, enforce lockdowns and prevent large gatherings — resulting in one of the lowest infection rates on the planet.

Major public investments have also been made in key innovation hubs, such as the Riyadh Techno Valley on the King Saud University campus, the nearby Riyadh Knowledge Corridor and the King Abdul Aziz City for Science and Technology — all reflections of a desire to create a knowledge-based economy, diversified away from oil.

Ironically, just as Riyadh emerges as a high-tech global city, there is a growing appreciation of its ancient cultural heritage. In the push for modernity and rapid expansion, most of Riyadh’s older buildings were razed. Now the prevailing mindset is changing in favor of Riyadh as a “city of culture.”

Riyadh has long had its share of well-curated museums, including the King Abdul Aziz Historical Center, the Royal Saudi Air Force Museum and the Al-Masmaq Fortress, but there is now a broader ambition to restore entire historical districts.

The old royal seat of Diriyah is being lovingly rebuilt as “Diriyah Gate,” using traditional methods and materials. The mission statement of the Diriyah Gate Development Authority is “to anchor our vision for the future on a jewel from the Saudi past.” Floodlit at night, against the backdrop of the Wadi Hanifah, it is a memorable sight and a reminder that Riyadh has been a work in progress for hundreds if not thousands of years.

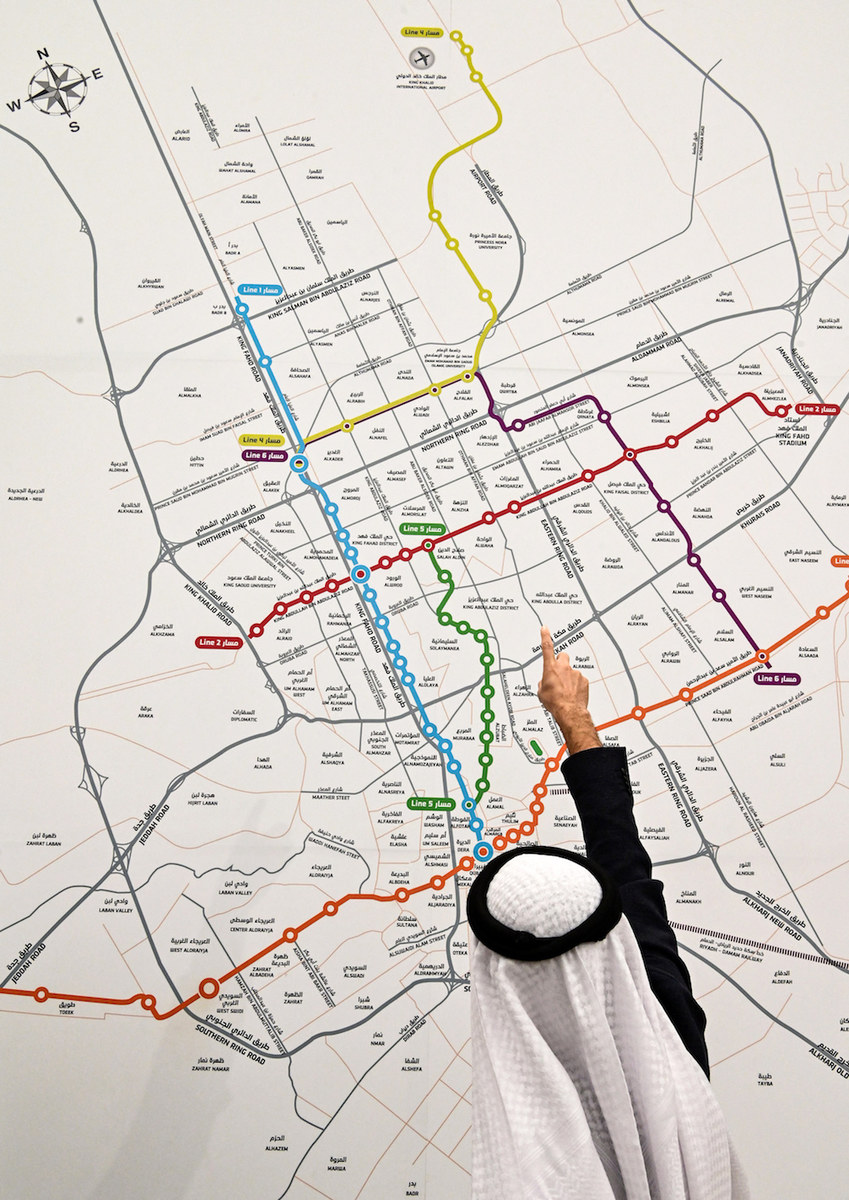

A man points at a map of the new Riyadh Metro in the Saudi capital on December 9, 2019. (AFP/File Photo)

Seven decades of intense urban growth has led to a recognition that some mistakes were made in the process — one being the lack of attention paid to natural beauty and public spaces. Riyadh does boast a few parks — King Abdullah Park in Malaz is especially popular for its fountain displays — but one has to admit the city is short on greenery.

That is all about to change. As a key element of Vision 2030, the government is investing no less than SR 80 billion in Green Riyadh to improve its environment, infrastructure, transport, leisure and sports facilities.

Billed as “one of the most ambitious urban reforestation projects in the world”, Green Riyadh represents an effort to create “one of the top 100 cities in the world and eventually achieving the highest rank possible.”

The vast King Abdul Aziz airbase is being repurposed as King Salman Park — five times the size of London’s Hyde Park, featuring lakes, sports venues, museums, galleries, cycling routes and even an opera house. The design was awarded the 2020 International Architecture Award from the Chicago Athenaeum Museum of Architecture and Design.

Some 7.5 million trees are to be planted, irrigated by recycled sewage water, and the supergrid will soon have an integrated metro and bus network, reducing the city’s dependence upon automobiles.

This is a welcome new chapter in the continuing story of Riyadh, as it transforms into a green and sustainable city for the benefit of generations to come.