DUBAI: For many, reading a newspaper or perusing a magazine over breakfast, catching up on the latest from around the world to follow the markets, the sport and the travel, is still the perfect way to start the weekend. But the world of print journalism, of broadsheets and tabloids, of exclusives and splashes, has been changing rapidly, with important implications not just for how we obtain information, but how we understand the world.

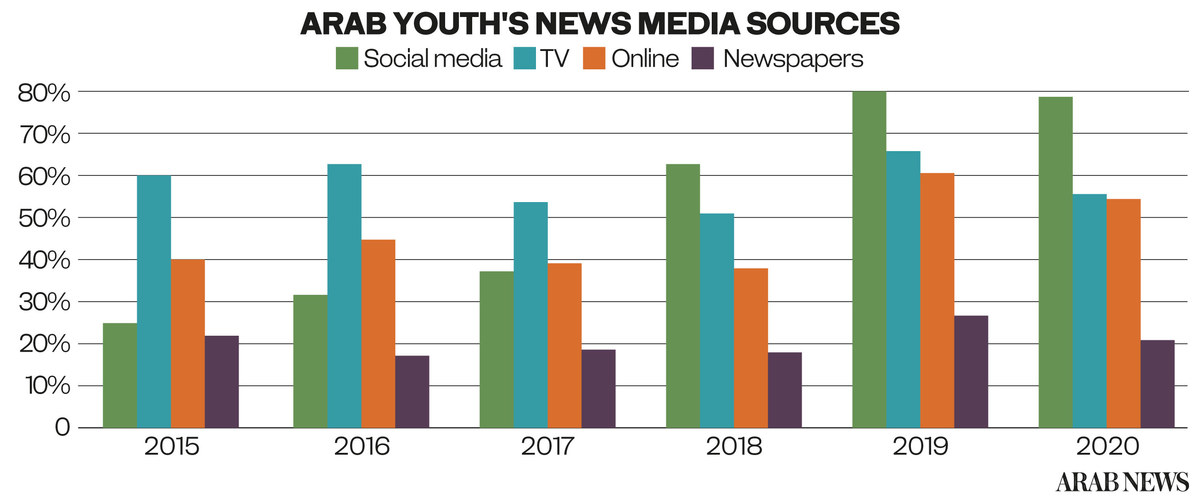

In 2020, a whopping 79 percent of young people in the Arab world received their news from social media compared with just 25 percent in 2015, according to the 2020 Arab Youth Survey.

By 2022, 65 percent of the world’s gross domestic product is set to be digitized, with direct digital transformation investments totaling $6.8 trillion between 2020 and 2023, according to the International Data Corporation.

It is no surprise then that digital transformation — the shift from hard copy of newspapers and magazines to devices in the media landscape — has been the buzzword of many meetings, conferences and business lunches. But what does it really mean and, more importantly, what does it mean for the print media industry?

In its latest report “Future of Media: Myth of Digital Transformation,” the Arab News Research & Studies Unit examines digital transformation in the context of the growth of big tech companies and the consequent impact on the publishing industry, and demonstrates why governments and regulatory bodies need to take notice and action.

Although the growth of digital and social media has revolutionized business largely for the better, it has had a devastating effect on the print media industry.

Globally and in the region, print media’s ad revenues have been steadily declining since 2008.

Between 2016 and 2024, digital’s share of ad spending in the Gulf Cooperation Council is predicted to increase by 20 percent, while that of print will drop by 13 percent, according to Choueiri Group’s estimates.

“Over the years, there has been a growing focus on performance — that is, generating sales by targeting consumers at the bottom of the funnel,” said Alexandre Hawari, CEO of publishing and events company Mediaquest and Akama Holding, referring to declining ad revenues.

As advertisers shift their budgets to digital channels, they find fewer outlets for their spending. Digital is dominated by just a few of the tech giants. In the Middle East and North Africa region, Facebook and Google command a massive 80 percent of digital ad spend, according to Choueiri Group estimates.

Today, just four companies — YouTube, Google, Facebook and Snap — represent 35 percent of the total global media ad spend, according to data from eMarketer. In contrast, traditional media’s share of spending globally has dropped from 81 percent in 2011 to 44 percent in 2021.

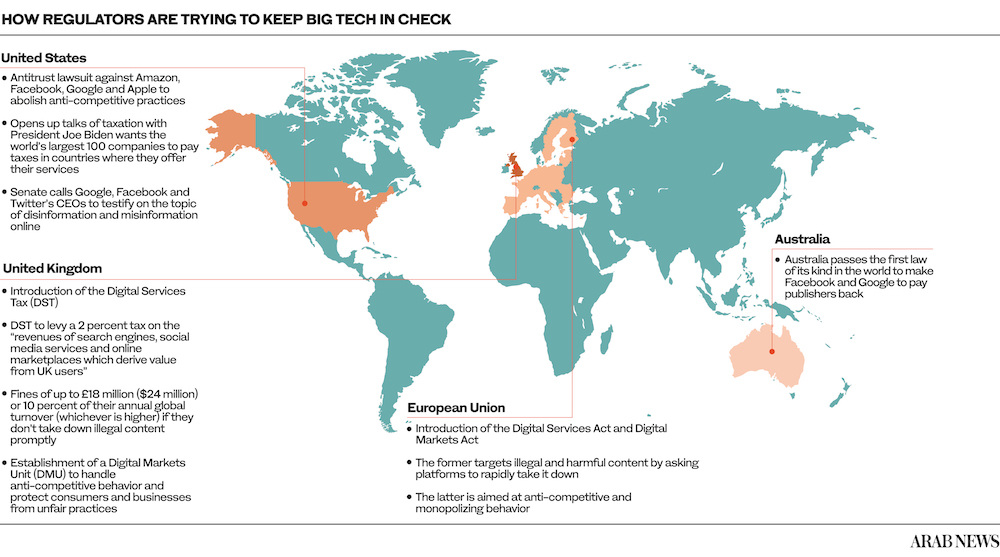

This concentration, and hence power, in the hands of a few companies is dangerous for both businesses and economies. The near monopolization of the digital ad industry means that government bodies are finding it difficult to regulate the tech giants. This has big implications for authenticity and accuracy.

A 2018 study by three Massachusetts Institute of Technology scholars found that fake news spreads far more quickly on Twitter than true stories. According to their research, false news stories are 70 percent more likely to be retweeted than true stories.

A propensity towards the scandalous, the outrageous and the scurrilous makes the rise of fake news and hateful and violent content on these platforms a matter of grave concern.

The growth of digital and social media has had a devastating effect on the print media industry across the globe. (AFP/File Photo)

As people constantly check the news on mobile devices, it becomes easy for fake news to become a top story as more people read and share it, while also shortening the life span of important stories.

Increasingly, journalists do not have the luxury of taking time to research and develop a story. When Bill Clinton was accused of having inappropriate relations with White House intern Monica Lewinsky, BBC journalist and author Gavin Esler spent a year investigating the truth. But when “the principal news source in the world is constantly telling lies,” said Esler, referring to former US president Donald Trump, it is very difficult for anybody, particularly journalists, to catch up.

Facebook also played a critical part in Trump’s victory in 2016. Brad Parscale, who led Trump’s digital campaign, said that 80 percent of the campaign budget was spent on Facebook. In an interview with WIRED magazine, he said: “Facebook and Twitter were the reason we won this thing. Twitter for Mr. Trump. And Facebook for fundraising.”

In 2018, the UN said that Facebook played a major role in hate and violence against Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar. According to an investigative report by The New York Times, members of the Myanmar military were the prime operatives behind a systematic campaign on Facebook that stretched back half a decade and targeted the minority group.

Nor is Twitter exempt from controversy. In early January, Twitter banned Trump following the Capitol Hill riots for tweets that were alleged to have incited violence by far-right protesters.

Supporters of former US President Donald Trump gather in front of the US Capitol Building on January 6, 2021 — Facebook on June 4, 2021 banned Trump for two years, saying he deserved the maximum punishment for violating its rules over the protesters’ deadly attack on the Capitol that followed. (AFP/Getty Images/File Photos)

Other leaders of dubious repute who continue to tweet and incite hatred on the platform, including exiled Egyptian cleric Yusuf Al-Qaradawi; terrorist-designated Qais Al-Khazali, leader of Asa’ib al-Haq in Iraq, and Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.

Then there is the question of funding. As audiences shift to digital platforms like Google, Facebook and Twitter for daily news, these companies profit from quality journalism while journalists and news media companies run up losses.

The second biggest source of traffic for Facebook and Google in every single country is news, said Juan Senor, president of Innovation Media Consulting Group.

It seems only desirable for big tech companies to not only invest in journalism, but also remunerate publishers fairly — something that regulators around the world are trying to enforce.

The idea of not paying in some form is “fundamentally meretricious and a flawed argument,” said Esler. Not compensating journalists and publishers is like taking milk from farmers and not paying them, he said. “Why should there not be some reasonable recompense from these massive organizations for something they make a profit out of?”

Sarah Messer, managing director at Nielsen Media in the Middle East, said that when social media platforms were growing, traditional publishers were slow “to understand how to mix their digital offerings with their traditional offerings.”

They were uncomfortable in the digital space, she added, leaving the gate open for digital publishers and big tech companies to move in.

Despite publishers digitizing their content, the relationship between big tech companies and news media has always been “dysfunctional,” said Senor of Innovation Media.

As big tech rewards people who get more clicks, experts say publishers of credible content are confronted with daunting challenges going forward. (Shutterstock)

The relationship is based on the premise that if you build an audience and drive a lot of traffic, you will generate a lot of ad revenue. But that is only true for the big tech companies, not for publishers, he added.

“They have always had the upper hand,” he said.

Arab News Editor-in-Chief Faisal Abbas said that today almost every newspaper now publishes its articles online and has a considerable social media presence.

The problem, in his opinion, is that the industry is not fair to credible publishers.

“We need to level the playing field so the same tools are available for publishing houses,” he said.

“The problem with the model here is that Google, Facebook and the big tech companies reward people who get more clicks.

“And in all of this, the biggest loser is the truth. There needs to be a way to be able to reward publications or media outlets that are producing this credible information, as opposed to punishing them, which is what’s currently happening.”