LONDON: More than three decades ago, Ebrahim Raisi made a name for himself overseeing the summary execution of thousands of Iranian political prisoners — an act considered one of Tehran’s first crimes against humanity.

Now, the religious hard-liner turned prosecutor is running for president of the Islamic Republic, and experts have warned that a flurry of disqualifications have effectively left the infamous jurist out in front in a one-horse race.

In what is set to be one of the country’s most restricted elections ever, June 18 will see Iranians go to the polls to vote for Hassan Rouhani’s replacement.

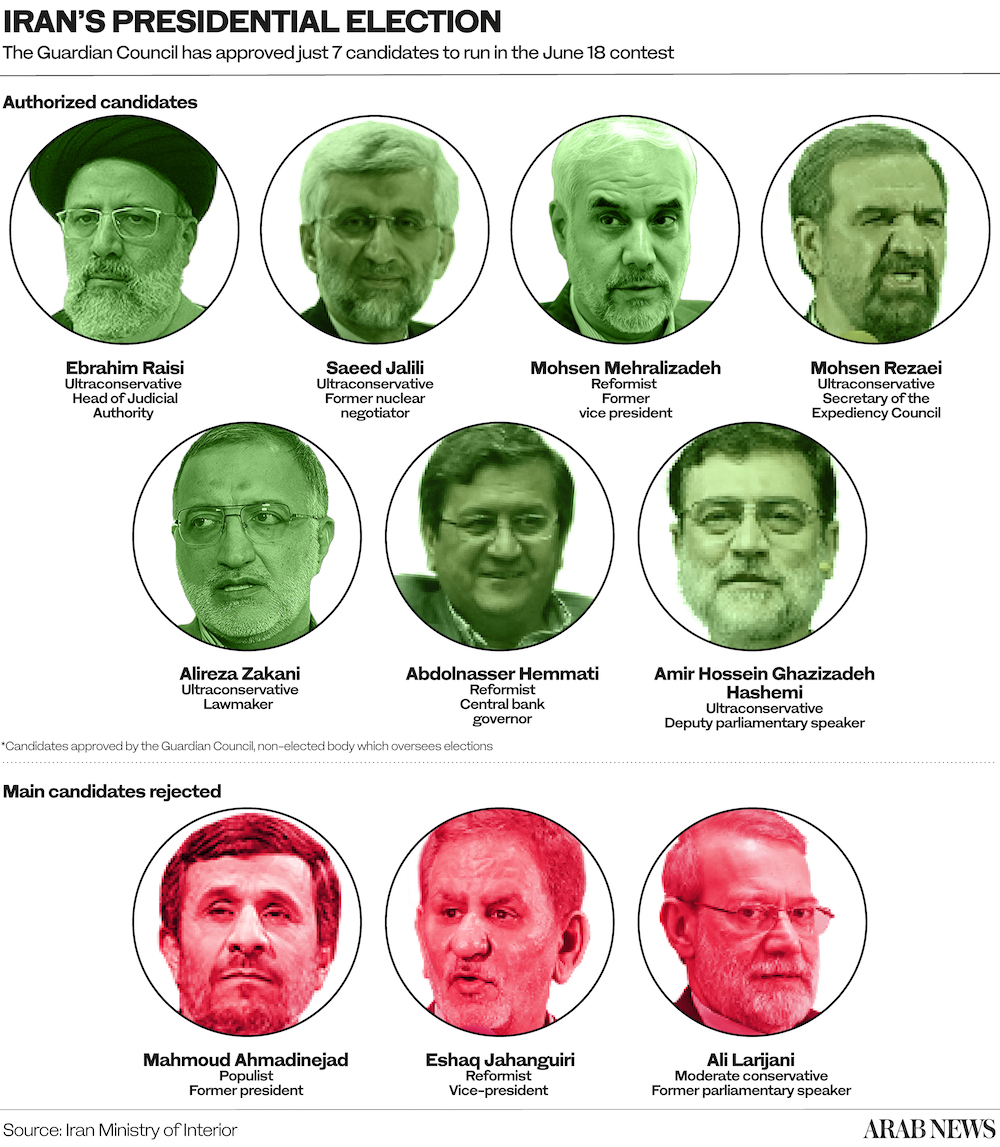

Last week the Guardian Council (GC), a body beholden to Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khamenei, announced the list of state-sanctioned presidential candidates.

Of the nearly 600 candidates that applied to run in the election, a huge proportion of them — some 585 people — were disallowed by the GC, including such well-known political figures as former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad and Ali Larijani, a former parliamentary speaker and Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) commander.

Only seven candidates now remain: Secretary of the Expediency Council Mohsen Rezaei; former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili; deputy parliamentary speaker Amir Hossein Ghazizadeh Hashemi; former vice president Mohsen Mehralizadeh; central bank governor Abdolnasser Hemmati; lawmaker Alireza Zakani; and Raisi, the Islamic Republic’s chief justice.

Mirko Giordani, founder of strategic advisory group Prelia, says the unexpected disqualification of Ali Larijani — previously seen as the only viable alternative to Raisi — has reduced the presidential election to a “one-horse race” in Raisi’s favor.

“Larijani was in the conservative camp, but he’s turned more moderate in recent times. He was poised to be the only possible contestant to Raisi — and, even then, the latter was supposed to win,” Giordani told Arab News.

The lineup is now so uncompetitive that incumbent Rouhani and even Raisi himself have both appealed for a wider variety of candidates.

Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on May 27, 2021 addressing parliament members via video connection during an online meeting in the Iranian capital Tehran, who urged Iranians to ignore calls to boycott next month's presidential election, after several hopefuls were barred from running against ultraconservative candidates. (AFP)

“Usually, Iranian elections are characterized by their strong turnout — around 70 percent — but current numbers are expected to be around 50 percent. That’s going to be a huge blow in terms of legitimacy,” Giordani said. “Even if Raisi does clinch the election, there’s going to be a lot of questions asked.”

During his time as an Islamic Republic insider, presidential favorite Raisi has overseen a catalogue of human rights abuses that have shocked Iranians, rights groups and the international community.

Among those he has condemned to death is champion wrestler Navid Afkari for his alleged role in anti-government protests. His killing in late 2020 sparked global outrage and protests from world sporting bodies — including the Olympics.

Perhaps his most heinous crime was his direct involvement in the “death commission” that ordered the execution of thousands of political prisoners in 1988. Dubbed a crime against humanity by Amnesty International, Raisi, then a deputy prosecutor for Tehran, oversaw the sham trials that condemned thousands to death.

Supporters of Iran's former president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad gather outside the Interior Ministry headquarters in the capital Tehran on May 12, 2021. In what is set to be one of the country’s most restricted elections ever, June 18 will see Iranians go to the polls to vote for Hassan Rouhani’s replacement. (AFP/File Photo)

“Groups of prisoners were rounded up, blindfolded and brought before committees involving judicial, prosecution, intelligence and prison officials,” Amnesty International reported. “These ‘death commissions’ bore no resemblance to a court and their proceedings were summary and arbitrary in the extreme.

“Prisoners were asked questions such as whether they were prepared to repent for their political opinions, publicly denounce their political groups and declare loyalty to the Islamic Republic. Some were asked cruel questions such as whether they were willing to walk through an active minefield to assist the army or participate in firing squads.

“They were never told that their answers could condemn them to death.”

The exact number of people Raisi put to death is unknown, but estimates range from 1 to 3,000 in the summer of 1988 alone. Other perceived dissidents faced torture and harassment.

“Many of those allegedly involved in the 1988 killings still hold positions of power,” Amnesty said, with Raisi arguably being the most prominent. Now, with the assistance of the Supreme Leader and the Guardian Council, he is on the path to the presidency.

“The regime is basically picking who is going to be the next president by disqualifying so many of the candidates who stood for election,” Meir Javedanfar, Iran lecturer at IDC Herzliya and a former BBC Persian reporter, told Arab News. “The chances of an upset, or anyone else winning, are low.”

Head of Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps Hossein Salami leaves after delivering a speech during a march to condemn the ongoing Israeli air strikes on the Gaza Strip, in the capital Tehran's Palestine square, on May 19, 2021. (AFP)

For Javedanfar, Raisi is the regime’s continuity candidate.

“A Raisi presidency will mean continuation of Ayatollah Khamenei’s foreign policy, which means acrimonious relations with America; continued support for Iranian presence in Syria, Lebanon, Iraq and Yemen; continuing the resistance economy.

“I also think that we’re going to see a crackdown on existing liberties, for example on social media. I’m even worried that a Raisi government could implement a national intranet.”

An intranet would allow Tehran to tightly control the flow of online information in and out of Iran by effectively cordoning off the Iranian cybersphere.

“The Islamic Republic is concerned about the dissemination of Western ideas among Iranians, especially feminism. Raisi would be the person to do this,” Javedanfer said.

Giordani says a Raisi presidency is likely to focus heavily on rooting out corruption, a trait that he says was a hallmark of the conservative’s tenure in the country’s controversial judiciary.

People, mask-clad due to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic, walk beneath a billboard depicting the Islamic Republic founder Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini (R) and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei (L) at Enghelab Square in the centre of Iran's capital Tehran on May 16, 2021. (AFP)

Ali Alfoneh, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Arab Gulf States Institute, believes the focus on corruption has always been highly selective — and political.

“Raisi dedicated his tenure as chief justice of Iran to engaging in a selective fight against corruption,” Alfoneh told Arab News. “Selective because Raisi, for the most part, targeted his political opponents and their close relatives.”

Alfoneh also believes, despite the media attention that the conservative-leaning list of presidential candidates has invited, the “hard-line” and “reformist” distinction is a misnomer that does not accurately depict Iran’s murky politics.

“The hard-line-softline dichotomy in Iranian politics is totally false,” said Alfoneh. “Due to the lack of formal political parties with written party programs, the ruling elites of the Islamic Republic organize in fluid networks around leader figures to secure personal gains.”

This handout picture provided by the office of Iran's Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on May 27, 2021 shows members of Iran's parliament saluting him via video connection during an online meeting in the Iranian capital Tehran. (AFP)

Therefore, “personal gains, rather than ideology” are “the organizing principle of Iranian politics.”

Alfoneh shares Giordani’s view about the June 18 election’s distinct lack of legitimacy in the eyes of the Iranian public.

“The ruling elites of the Islamic Republic are subjected to a permanent purge, and over the years, the regime has become less representative of Iran’s population,” he said.

“This has already caused problems for a regime, which, for all its authoritarianism, is sensitive to public opinion.”

----------------

Twitter: @CHamillStewart