DUBAI: After recently coming fifth in the UNESCO International Competition for the Reconstruction and Rehabilitation of Mosul’s Al-Nouri Mosque with his team, Samir Nicolas Saddi has big plans for heritage rehabilitation around the Middle East.

The Beirut-born Canadian-Lebanese architect, who founded the Arab Research Center for Architecture and Design of the Environment (ARCADE) back in 1990, has dedicated his life to documenting the fragile traditional environment in the Middle East and proposing innovative approaches to sustainable architecture — as he did in the UNESCO competition.

“The aim of rebuilding Al-Nouri Mosque is very symbolic, given the level of destruction occurring in the Arab world,” he told Arab News. “It was especially symbolic for me as I am very concerned with how to rebuild the Arab world, particularly the countries which have been devastated by war. So it was a great opportunity.”

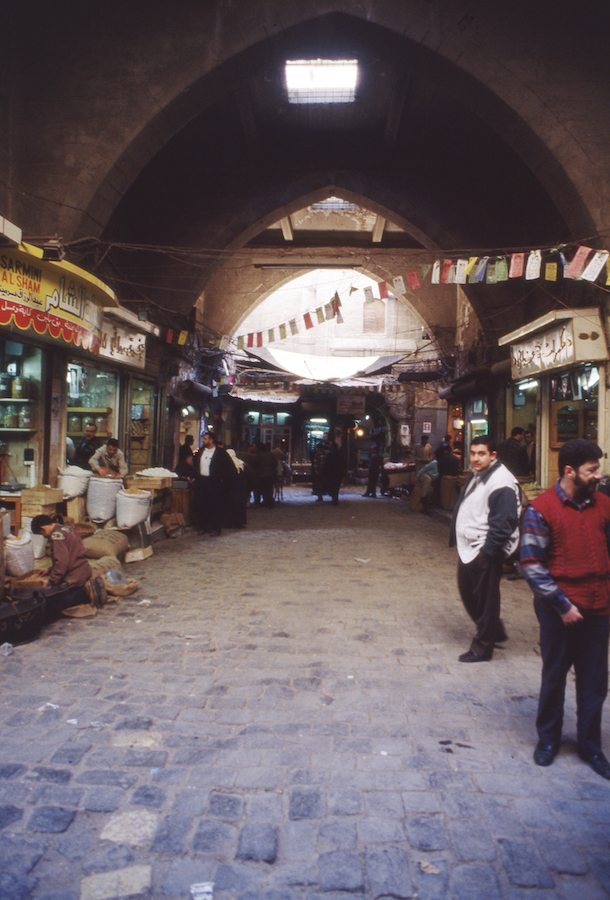

A tragedy happened when Saddi was preparing to visit Syria to document Aleppo. (Supplied)

Saddi’s team of architects from France and Dubai looked at how to integrate the mosque within Mosul’s architecture, which he describes as having a “unique historic pattern.” Their aim was to find a way to make it available for local people to rebuild, based on their knowledge of their own architecture.

“We had a lot of passionate discussions about architecture in the Arab world, especially the historic cities,” Saddi explained, as he spoke of his interest in opening up the Gulf to young French consultancies. “My role was really to inform the team about the Middle East. I might also be working with the team on other projects and opening up France to the Middle East and to the Arab world, which is great, because the Arab world — especially the GCC — is mostly collaborating with American and British consultants.”

Saddi’s own journey dates back decades, starting in Lebanon when he finished his studies as an architect in 1974. At the time, it seemed the country was heading into a fruitful and prosperous era, and Saddi was already working with a large architectural firm on projects to be developed over the next 10 years. But all of that abruptly came to a halt when the country’s devastating civil war broke out in 1975. “At first, we thought it would only last a couple of months, and then it took 19 years” Saddi told Arab News.

Old Aleppo souks. (Supplied)

“I realized that there was no time to document what Beirut was because we had immediately entered into a zone where people were fighting and my aim was really to document Beirut city center, which was an amazing place, and other places in the capital,” he said.

For Saddi, documenting historic or traditional architecture was crucial in such a fast-moving world in which time seemed to be running out for such places.

A similar tragedy happened when Saddi was preparing to visit Syria to document Aleppo, Damascus and other ancient Arab cities with rich heritage. “But the war happened, so Aleppo was gone, and so on and so forth,” Saddi said. “I visited Aleppo in 2000 for a couple of days and I took some pictures but today, it is ruined.”

For him, old Jeddah — also known in Arabic as the Balad — is one of the most significant of those cities. (Supplied)

The main idea behind ARCADE, he said, is to “document these places because, at least, if you have documentation, you can photograph the urban architecture, and later on elaborate a lot of research that will consolidate modern contemporary architecture and projects.”

He mentioned the fact that international architects commonly work on projects in the Gulf and the Middle East today, despite not really being familiar with the essence of the region’s architecture. “So the design is often coming from far away and is not related to the reality of the people on the ground,” he said.

He spent three years taking photos of old Jeddah, from 1994 to 1997. (Supplied)

Saddi is now working with his peers in Europe on a book about historic Arab cities in the Middle East. For him, old Jeddah — also known in Arabic as the Balad — is one of the most significant of those cities. He spent three years taking photos of old Jeddah, from 1994 to 1997, with the aim of safeguarding the old city and participating in its redevelopment.

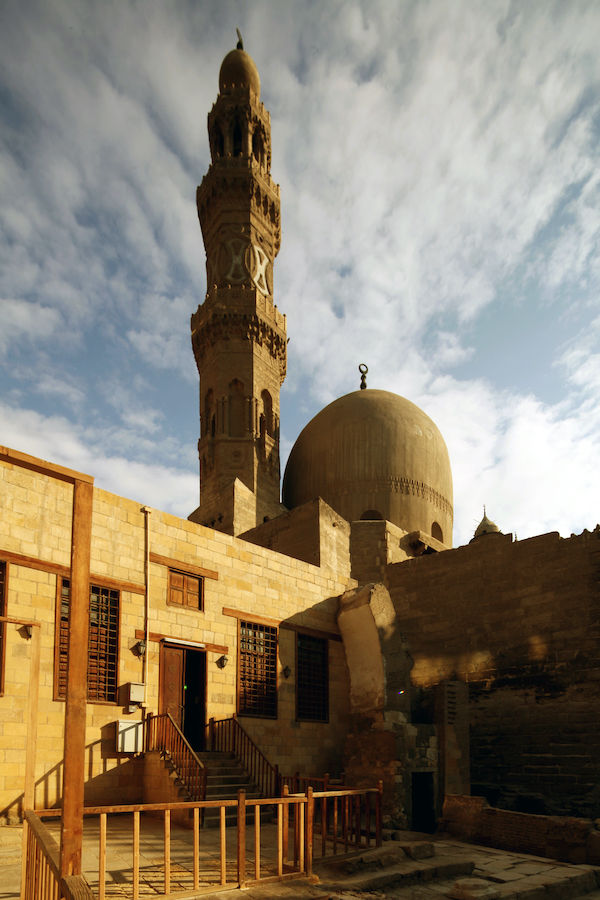

Old Cairo is another city that ranks high on his list. “Today, it is a very big project,” he noted. “In 2017, I had time to go and really document the historic Cairo, which is amazing, and there is a lot to do. Today, it is a real project — Egypt is keen on restoring and rehabilitating Old Cairo.”

He described it as a “monumental zone” with exceptional buildings representing a perfect example of Islamic architecture, along with old churches. “Cairo is really very important to preserve,” he said.

Old Cairo is another city that ranks high on his list. (Supplied)

Saddi spoke of many other cities in the Arab world which he believes it is crucial to rehabilitate so that people remember and recognize them as the beacons of rich urban architecture that they are.

Ultimately, his goal is to demonstrate to the world the Middle East’s unique heritage, while communicating to the younger generation of architects and urban planners in the Arab world how crucial it is to develop their architecture based on their heritage.

Old Tripoli. (Supplied)

“We should not copy,” he said. “In the last 50 years, architects were unfortunately copying the heritage, but it is not about that. It is about going further and really connecting with this heritage and continuing its spirit, like what is happening in Mosul.”

For Saddi, such projects are not about simply recreating the past, but rather about introducing a new spirit that is connected to the past. “This is my hope — that somehow we can achieve this through publications and workshops, which is why I created ARCADE,” he concluded. “It is about research. Unfortunately, the Arab world is not yet keen on allocating budgets for research. The west was — and is still — allocating huge budgets towards this, but not the Arab world although we have the means to do it, so it is a shame. But I have hope for the future.”