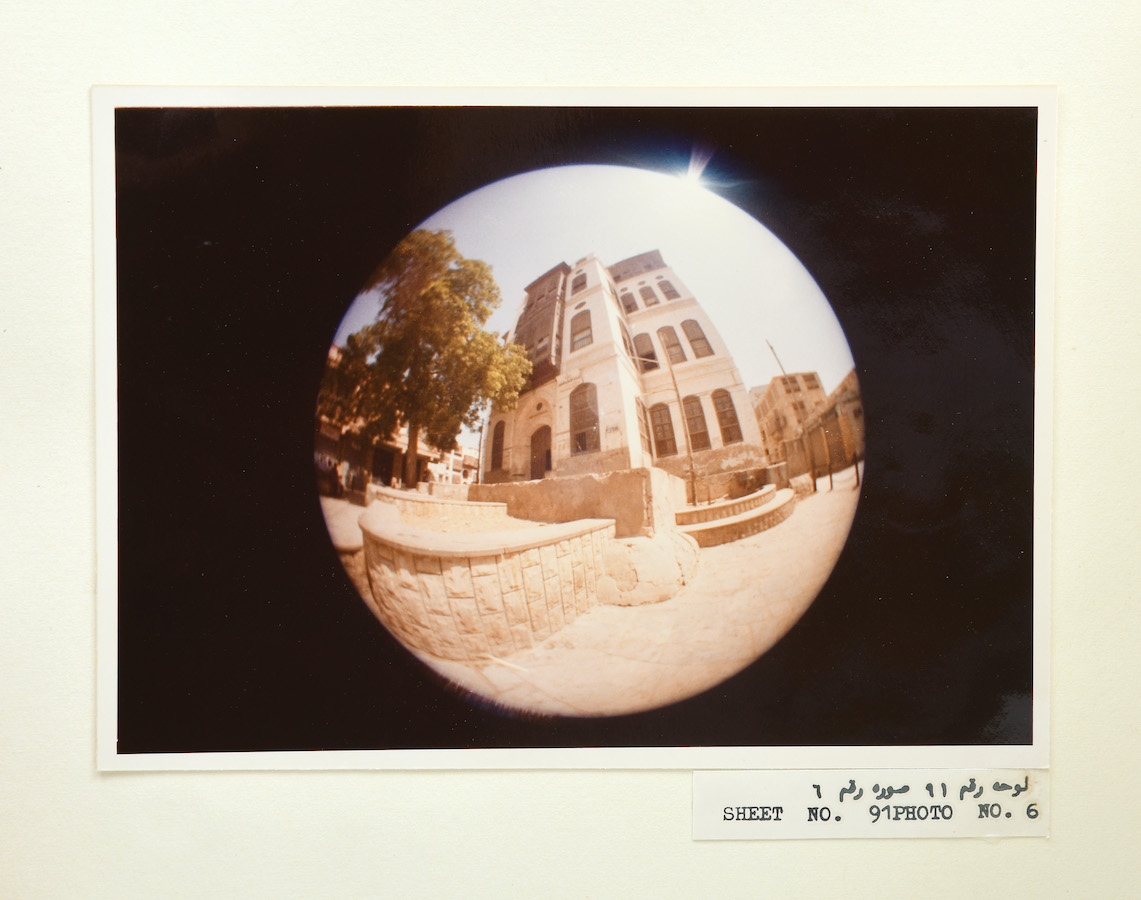

A visual record of a Jeddah landmark

This “apparently unique” bespoke album contains 120 original photographs of Jeddah’s well-known Bayt Nassif, taken before its restoration in the early 1980s. The Saudi government purchased this historic landmark in 1975 and initially used as a library, but it is now a cultural center that hosts exhibitions and other events. King Faisal’s decision to rehabilitate the building “provided an enlightening and inspiring model for sustainability in historic areas,” according to a book cited in the Peter Harrington catalogue.

Located on the main street of Jeddah’s historic Al-Balad district, the house was built for the then-governor of Jeddah, Sheikh Umar Effendi Al-Nassif between 1872 and 1881 and is now, the catalogue states, “widely recognized as one of the most important surviving examples of Red Sea coralline limestone architecture.” The house was later used by King Abdulaziz bin Saud as his primary residence in the city until Khuzam Palace was constructed.

Until the 1920s, Bayt Nassif was also the site of the only tree in Jeddah’s old city — so the building is also known locally as The House of the Tree. That neem tree still survives and can be seen in images in this book.

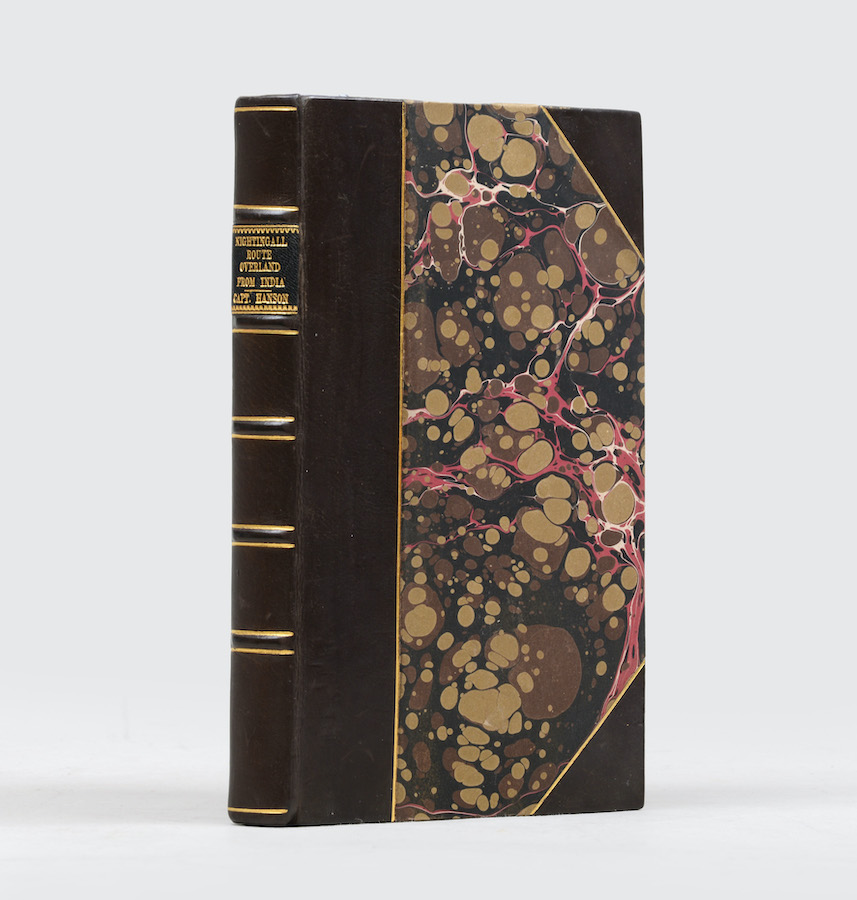

Account of a 19th-century journey from Jeddah to Egypt

In 1819, Sir Miles Nightingall, commander-in-chief of Britain’s Bombay Army, was returning to England from India when their ship “Teignmouth” was grounded on a sandbank in the Gulf of Aden. Having got their boat moving again, Nightingall and his entourage — including Captain James Hanson, the author of this work — headed to Jeddah “where they were welcomed by the Turkish governor, newly installed following the restoration of Ottoman rule in Egypt. Having taken advice from Henry Salt, consul-general in Egypt, they decided on an overland route across the desert that would take in the ‘most interesting and marvelous ruins’ at Thebes.” Hanson’s book describes — and maps — their journey from Kosseir (now Quseer) on the Red Sea westwards inland to Kennah (Qena) on the Nile, just east of Dendera “passing ruined forts, ‘Hills having the appearance of Tombs’ and ‘Sterile Desert - not a blade of Vegetation.’”

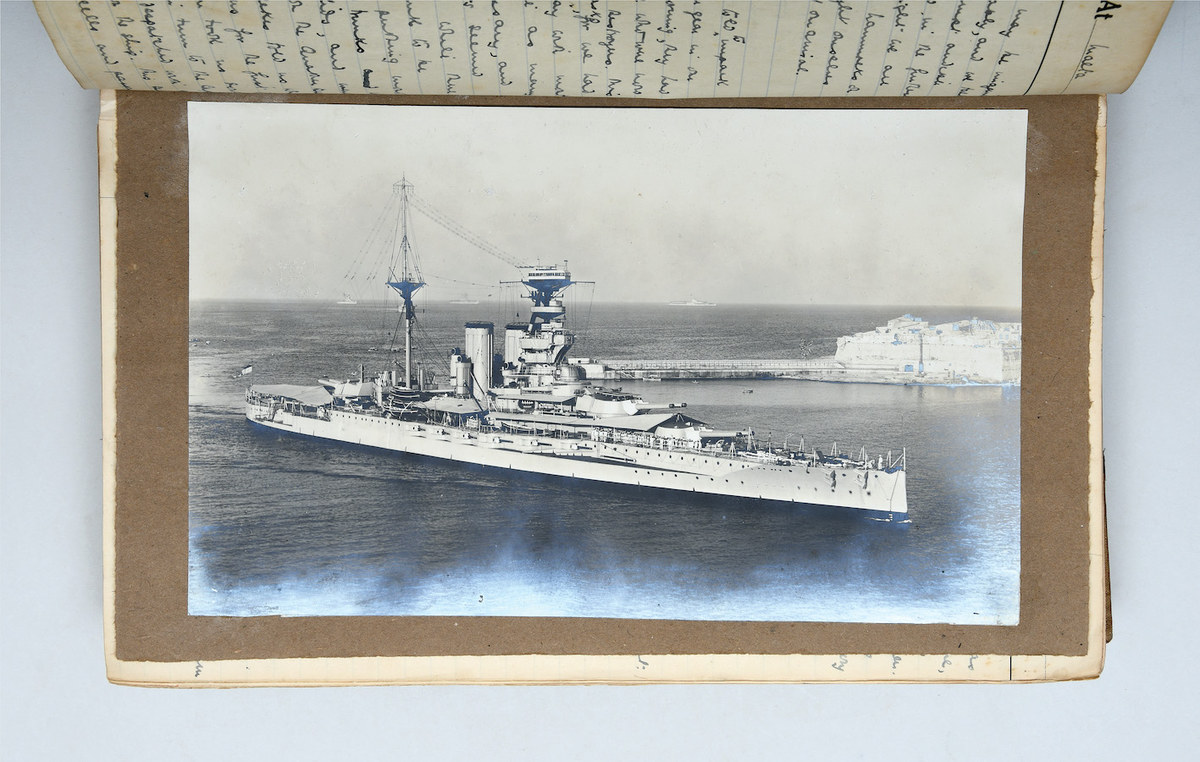

Journals of a British naval officer in the Arabian Gulf 1928-51

This three-volume manuscript relate to Midshipman Francis Wyatt Rawson Larken’s service in the British Royal Navy in the early-to-mid 20th century, for part of which Larken was stationed in the Arabian Gulf around what the British then called the Trucial States, which later became the UAE. The books were unpublished at the time, and according to the catalogue, include “a compelling account of a visit to Dubai and an on-board reception for the Trucial Sheikhs.” Those visitors would have included Sheikh Saeed bin Maktoum Al-Maktoum of Dubai, Sheikh Shakhbut bin Sultan Al-Nahyan of Abu Dhabi, and Sheikh Sultan bin Saqr Al-Qasimi of Sharjah, among others.

“There were some 8 or 10 of the higher cast (sic.) on board and these were taken round the ship by the Admiral and the Captain while their followers stayed on the Quarter Deck. … They all then congregated on the Quarter Deck where the band played. They then left in their respective barges — ornate and rather splendid motor dhows, the various Sheikhs receiving salutes — the number of guns ranging from 6 to 1 in ratio to their importance. They brought us gifts of Beef and Melon Jelly … and were sent away with Gold Flake Cigarettes and chocolate,” Larken writes. “Every man carries his broad curved belt knife — heavily set with worked silver — and the chief ones wore splendid ‘Bournous’ of gold work cloth. All were fine upstanding men very much like the Sheik of fiction.”

During his service, Larken also visited Aden, Muscat, Sohar, Sur, Khasab and Khor al-Jarama in modern Oman, as well as Dubai and the island of Sir Abu Nu’ayr in what is now the UAE.

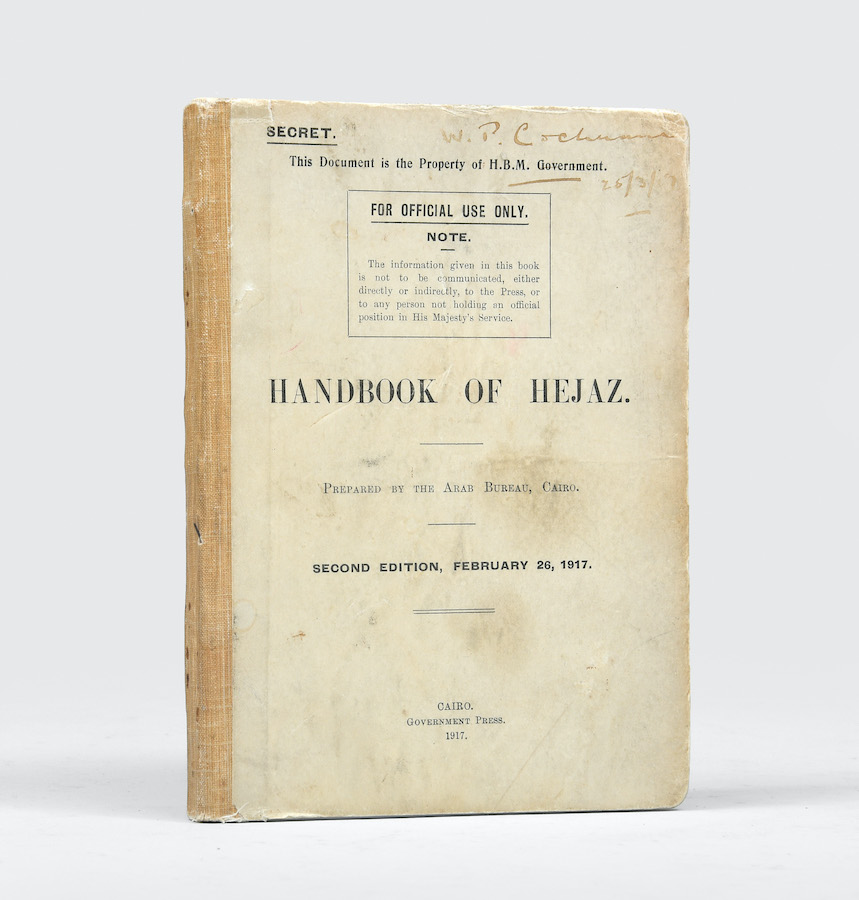

British intelligence manual from the time of the ‘Arab Revolt’

This manual includes material from T.E. Lawrence (aka Lawrence of Arabia) and was produced by the British Arab Bureau as a guide to the “tribal and political organization, geography and passable routes in the region” at the time of the military uprising by Arab forces against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, led by Hussein bin Ali, the sherif of Makkah, backed by the British government. One of the “passable routes” that Lawrence himself gave information on was that from Madinah to Makkah.

This copy previously belonged to William Cochrane, deputy to Colonely Cyril Wilson, the British Agent at Jeddah. Among Cochrane’s duties was the organization of the Hajj for Muslims from British India, and he reportedly “took charge of the £125,000 in gold sovereigns that was brought to Jeddah each month by the Red Sea Patrol of the Royal Navy” — Hussein’s subsidy from the British for the uprising.

Eyewitness account of a Danish expedition to Arabia in the 1760s

An English translation of a two-volume account of the 1761-7 Danish expedition to the region — “the first great scientific expedition to the Middle East” — by the surveyor Carsten Niebuhr, the only member of that expedition to survive.

“The party left Copenhagen in early 1761, travelling via Constantinople to Alexandria and spending a year in Egypt, ascending the Nile and exploring Sinai. They then crossed from Suez to Jeddah and sailed down the Arabian coast to al-Luhayyah in Yemen, making frequent landfalls, before continuing overland to Sana’a via Mocha, with two members of the party dying en route. On returning to Mocha, the remaining four collapsed with fever and were put on a ship bound for Bombay, with only Niebuhr surviving the sea voyage.”

Niebuhr’s account of the trip, the catalogue says, “has long been considered one of the classic accounts of the geography, people, antiquities and archaeology of the Arabian Peninsula and wider Middle East, with maps which remained in use for over 100 years” and is “a singularly important account of the Gulf in this still-obscure period.”

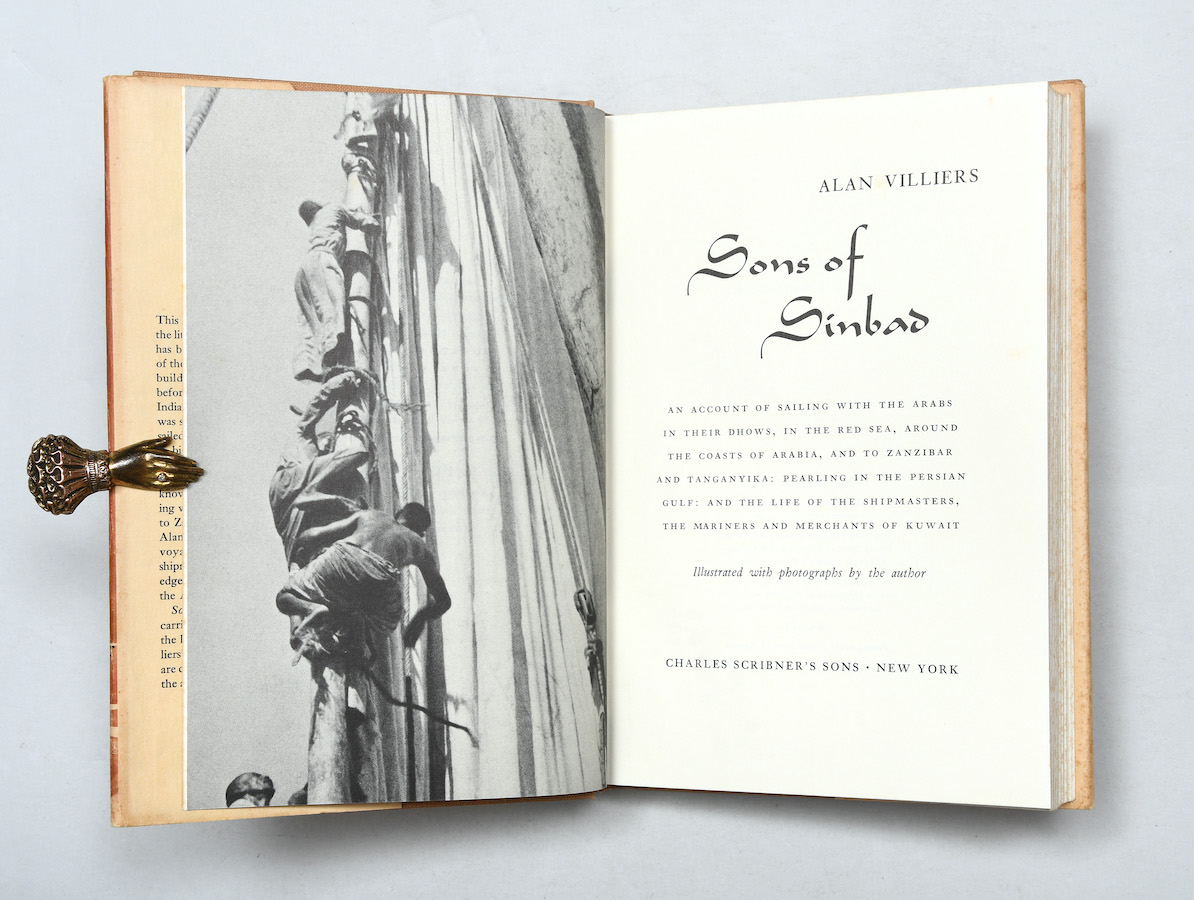

A chronicle of traditional Arab seamanship

The full title of this work from 1940 is “Sons of Sinbad. An Account of Sailing with the Arabs in their Dhows, in the Red Sea, around the Coasts of Arabia, and to Zanzibar and Tanganyika; Pearling in the Persian Gulf; and the Life of the Shipmasters, the Mariners and Merchants of Kuwait.” As it suggests, the book — written by Australian adventurer Alan Villiers — is a comprehensive account of traditional seamanship, boat building and trade in the region at a time when those traditions were coming to an end with the discovery of oil. It includes dozens of illustrations from photographs and charts too.