WASHINGTON D.C.: After a tumultuous four years of Donald Trump’s rule, Joe Biden has entered the White House with a packed domestic agenda, not least the ongoing pandemic and its economic repercussions but also the gnawing issue of race relations. As such, one might expect Biden to place America’s foreign relations on the backburner, at least for the time being.

However, Biden has a strong track record on high-level diplomacy, chalking up several years of engagement with America’s friends and foes, projecting US national interests abroad. Now that he has assumed the highest office in the land, he has pledged to restore America’s image on the world stage.

Coincidentally, Biden’s tenure began just days before long-awaited talks between Greece and Turkey took place in Istanbul — the latest in the protracted territorial dispute which has long threatened the peace of the Mediterranean Sea.

A handout photo released by the Greek National Defence Ministry on August 26, 2020 shows ships of the Hellenic Navy taking part in a military exercise in the eastern Mediterranean Sea, on August 25, 2020. (AFP/Greek Defense Ministry/File Photo)

Delayed by several months, and following a relative easing of tensions, talks between Greece and Turkey are, on the surface at least, an exercise in minimal expectations. Exploratory talks resumed after a pause of five years, picking up where they left off in 2016.

Little progress toward normalizing relations was made between 2002 to 2016, during which time some 60 rounds of talks took place. There is little sign things will be any different this time around.

However, Biden is not Trump. He will need very little time getting up to speed on the dispute in the eastern Mediterranean and his active involvement in the State Department’s handling of the issue is beyond doubt.

Furthermore, Biden will end the Trump-era practice of direct diplomacy between the White House and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, preferring instead to act through the standard institutional channels.

Greece has reason to feel optimistic about the US stance. Biden has on numerous occasions endorsed the Greek position on de-escalation, solving outstanding issues through dialogue and recourse to international law. He is also a supporter of the religious rights of the Greek minority in Turkey, and especially of the role of the patriarchate in Istanbul.

By any measure, Greek-US relations are at their peak, having been strengthened during the Trump years and made stronger through multiple agreements on trade and mutual defense.

FASTFACT

Greece-Turkey

* 11 Turkey’s rank in Global Firepower military strength.

* 29 Greece’s rank in Global Firepower military strength.

* $18.2b Turkey’s annual military budget.

* $7b Greece’s annual military budget.

Biden has also surrounded himself with seasoned diplomats and advisers who worked with him during his eight-year tenure as Barack Obama’s vice president, and whose concern for peace and stability in the region is echoed in Greek rhetoric and policy initiatives.

By contrast, a big question mark hangs over Washington’s Turkey file. Ankara’s flourishing relationship with Moscow and its purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system has led to US sanctions that Biden will be in no hurry to lift.

Turkey’s position in NATO has been weakened, leaving member states including France questioning its reliability. Indeed, Washington considers the presence of S-400s on Turkish soil as a threat to its F-35 fighter jets and to NATO defense systems in general.

This is not the only issue blighting the bilateral relationship. Ankara continues to complain about the perceived US role in the 2016 coup attempt and rejects US charges levelled against its state-owned Halkbank concerning its alleged role in helping Iran evade US sanctions.

Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan (L) and Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis (R) shake hands in front of the Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu (C) during a bilateral meeting on the sidelines of the NATO summit at the Grove hotel in Watford, northeast of London. (AFP/Murat Cetinmuhurda/Turkish Presidential Press Service/File Photo)

More telling still is the view which emerged from talks between Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security adviser, and Bjoern Seibert, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen’s cabinet chief, who “agreed to work together on issues of mutual concern, including China and Turkey,” according to a White House statement.

Linking Turkey with China, the main US geopolitical adversary, is a blow to Erdogan’s hopes of a close relationship with the new Biden administration.

If the US chooses to get involved in the Greece-Turkey dispute, Athens rightly expects to reap the rewards. Yet it would be premature to assume the Biden administration will automatically apply pressure on Turkey.

Firstly, the exploratory talks are informal and require no mediation. Talking directly to one another, even if disagreements are substantial, is preferable to having external sponsors.

Secondly, Turkey is currently trying to recalibrate its relations with the West as well as countries closer to home, including the Gulf states and Israel. The US is likely to give Turkey the benefit of the doubt, at least in the initial stages of the new administration, and give it time to prove its willingness for constructive cooperation.

Thirdly, for all of Turkey’s recent acts of bravado, the country remains a potentially critical ally for the US in an intensely volatile region. Not only does Turkey possess NATO’s second largest army, it also has the strategic positioning to act as a brake on Russia’s ambitions in the Middle East, particularly in Syria.

By the time talks concluded on Jan 25, a few facts stood out.

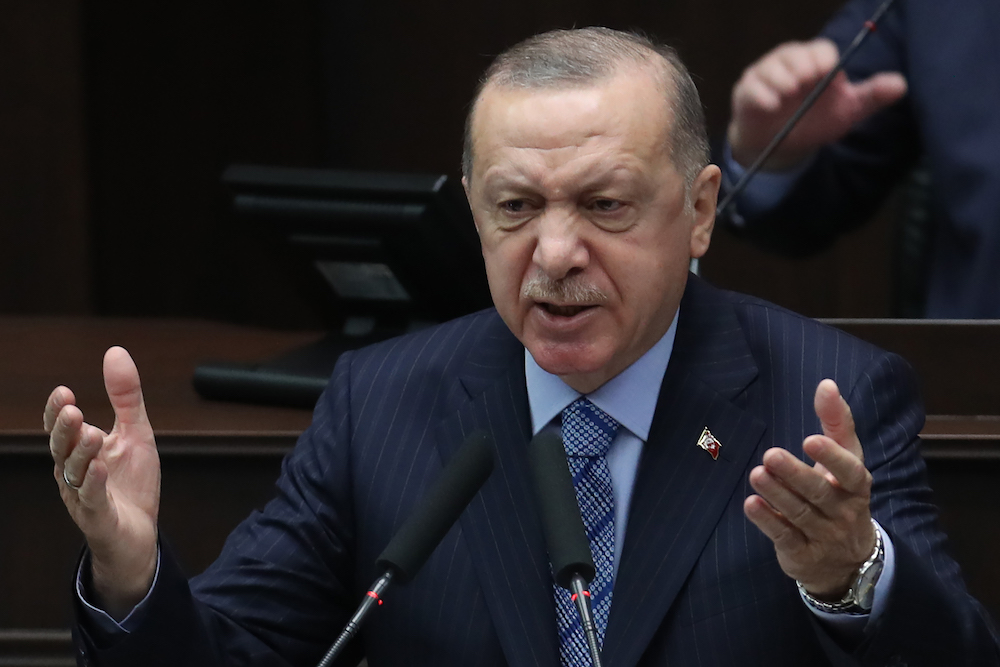

Turkish President and leader of the Justice and Development (AK) Party Recep Tayyip Erdogan speaks during a parliamentary group meeting on January 27, 2021 at the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (GNAT) in Ankara. (AFP/File Photo)

Although the talks were intended to take place at a merely technical level, the Turkish delegation included Erdogan’s trusted advisor Ibrahim Kalin. The move was likely designed to underscore Turkey’s sincerity in bringing the talks to a successful conclusion, a message that its foreign minister communicated to EU officials the previous day.

Another interesting fact is that both sides followed standard practice by not revealing the content of their talks. This is largely a positive sign, since press leaks are usually aimed at shifting the blame onto the opposite side and undermining prospects for a positive result.

More encouraging still, Greece and Turkey have agreed to proceed with the next round of talks in March, this time in Athens.

Washington, just like Brussels, welcomed the talks and highlighted the importance of dialogue between the two sides. Confirming its attempt to adopt an equidistant approach, the US will continue to encourage both Athens and Ankara to resolve at least some of their disputes.

For Greece, these are limited and specific: the determination of the continental shelf in the Aegean Sea and the delimitation of the two countries’ respective Exclusive Economic Zones (EEZ).

For Turkey, on the other hand, the list includes issues such as minority rights, the demilitarization of the Greek Dodecanese islands and the alignment of Greece’s sea borders on the Aegean (6 miles) with its airspace in the same region (10 miles).

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis has reason to be optimistic about the US stance during the Biden administration. (AFP/File Photo)

What is certain, save for any big surprises, is the US (and the EU) will refrain from further sanctions on Turkey.

Pre-existing problems pertaining to the Aegean dispute and the Cyprus issue, the primary bone of contention for many decades, have recently been compounded by zero-sum games on hydrocarbon exploration in the eastern Mediterranean, as well as the migrant and refugee crisis, fueled further by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The fact that other states with interests in the region, such as Cyprus, Israel, France, Italy, Libya and Egypt, are now part of the larger Eastern Mediterranean dispute raises the stakes and pushes Greece and Turkey to adopt maximalist positions.

For all of Washington’s desire to see normalization, it is highly unlikely that concrete progress will be made in the coming months.

------------------

Twitter: @dimitsar