LONDON: In the tense environment of the terrorist assassinations which have affected France in the last weeks, the question of the integration of French people of Arab origin — more specifically Muslims — and their conformity with “the values of the republic” is back to the fore of political discourse.

By focusing on a minority of Muslim extremists, right-wing politicians and polemicists who monopolize television platforms continue to instill in people’s minds the idea that French Muslims as a whole are separate citizens and “enemies of the inside” summoned to prove their sense of belonging.

But as the new Arab News en Francais/YouGov study shows, French people of Arab origin are well integrated. Among the representative sample of 958 French Arabs surveyed, a significant proportion had a good level of education, 65 percent of them were employed, 10 percent were unemployed and 55 percent had completed higher education.

They are generally familiar with French history, from Louis XIV to the latest political developments.

Contrary to popular belief, around half of those surveyed believe that their sense of belonging to French society has not been impacted by their religion (48 percent) and their origin (45 percent). The other half of those polled are divided between those who think that Islamic or Maghrebi origin has fostered their sense of belonging and those who think that it has been an obstacle to their inclusion in French society.

Although integrated, the French of Arab origin suffer from a bad image that sticks to their skin. Almost two-thirds of those polled (64 percent) believe that Arabs in France are perceived negatively. This feeling is even stronger among those aged over 55 (73 percent). The term “Arabs” gradually came to the fore in the early 1970s to designate Maghreb immigrant workers and their families, and was gradually taken over by the far right and the National Front.

It was then assimilated to delinquency and violence in the suburbs, but also linked to degrading imagery inherited from the colonial empire, as shown for example by the use of terms such as “savage” or, in more recent times, “savagery.”

The semantic shift towards the term “Muslim” took place at the start of the 1990s. It was already common in the 1950s and 1960s to designate the status of colonized people in Algeria. The term has returned to the fore, notably following the Creil headscarf controversy of 1989, and has been associated with religious conservatism and rejection of secularism.

From 1995, France was also affected by a wave of radical Islamic attacks, giving rise to a growing conflation between Muslims and terrorists. This trend has intensified since a surge in violent extremism in 2015 in France, especially as they are exploited for political ends. Islam and “Muslims” are regularly singled out in the media. Far-right polemicist Eric Zemmour has made it his specialty, going so far as to compare Islam to Nazism.

Politicians like former Republican presidential candidate Francois Fillon made it clear that “there is a problem with the Muslim religion” and that “a significant part of the Muslim community refuses to integrate.”

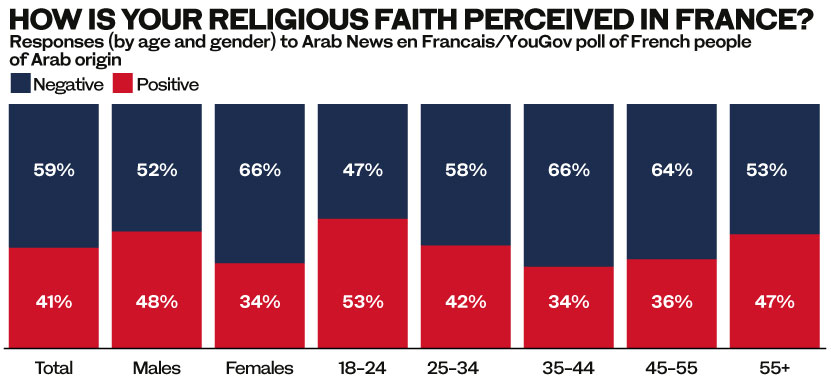

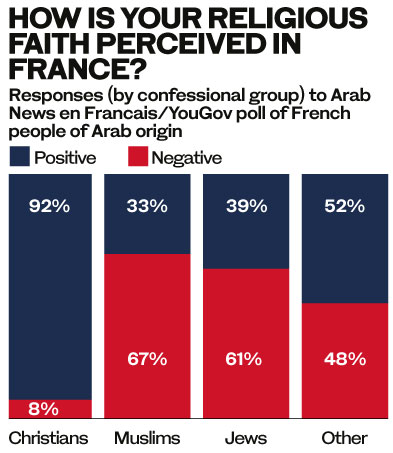

It is therefore not surprising that, in this climate of tension around Islam, more than two-thirds (67 percent) of Muslims polled in the YouGov poll believe that other French people have a negative perception of their religion.

But — and this is another lesson from the opinion poll — the negative image of religion is not just about Islam as such. Indeed, 61 percent of Jews of Arab origin also say that their religion is frowned upon by French citizens. In contrast, the perception is completely reversed for Christians of Arab origin, 92 percent of whom say that their beliefs are viewed positively.

These negative perceptions translate into discrimination, particularly in hiring. In the Arab News en Francais/YouGov survey, about three in 10 respondents said religion or racial origin has had a negative impact on their careers. This feeling is especially true for men, whether it concerns ethnicity (35 percent) or religion (33 percent).

Women, on the other hand, believe that neither religion (61 percent) nor racial origin (53 percent) has had an impact on their professional trajectory. For 36 percent of those polled, it was even the ethnic origin of their name that penalized them the most in their hiring process. A survey carried out by Institut Montaigne in 2015 showed that in France, Mohammed is four times less likely to be recruited than Michel.