DUBAI: Jewelry has been a passion in Nasser Farsi’s family for over a century, says the 34-year-old Saudi from Jeddah, who is keeping the tradition alive. The family jewelry brand, Farsi, is among the Kingdom’s oldest.

First established by his great-grandfather Mohammed in 1907, the store handles every stage of the jewelry-crafting process, but with a distinctive local touch steeped in history.

“I am the fourth generation in the business after my grandfather and father worked as jewelers in Makkah and Jeddah,” Farsi told Arab News.

As technology has evolved and customer demands have changed, so too has Farsi been forced to move with the times. “Every business needs to adapt through the year,” he said. “So, whatever my father did in the 1970s — the best at the time — doesn’t apply today. And what I’m doing today won’t be applicable in the future.

Nasser Farsi

“Every generation needs to come in and add to whatever makes their business adapt to the current times — manufacturing, branding and the designs of the jewelry are very different to before.”

Farsi should know. He learned his craft through the family and studied under some of the best gemologists in the world.

After finishing school in Jeddah, he first traveled to the US to study finance in Arlington, Virginia, before pursuing a master’s in finance in Miami, Florida. “I wanted to have managerial skills to be both the jeweler and the one operating the business,” he said. “My father did his undergraduate in general commerce and his master’s in accounting as well.”

Soon after, Farsi graduated in gemology and jewelry design from the well-reputed Gemological Institute of America (GIA) school in Florence, Italy — at that time the largest gemology school in the world — before returning to Jeddah in 2012.

“My father had to let the practice grow on me. I had to pay for anything I wanted when I was younger by working in the shop,” he said. “He wanted to make the most out of my free time and I am glad he did — because it became a passion.”

Now that he has inherited the family business, Farsi is out to make his mark. Pearls were the mainstay of the brand in the early days, later growing to include diamonds. Finer metalwork techniques were adopted as technology improved, allowing the business to create the lighter and more delicate designs favored by customers today.

“What was impossible 10 years ago by hand is possible today, so it made everything lighter and easier for the consumer,” Farsi said. Heavier gold pieces in particular seem to be falling out of favor.

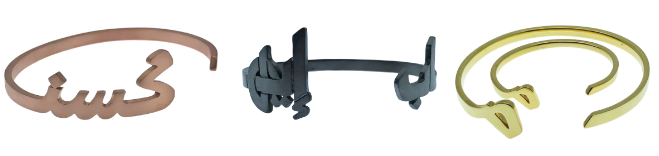

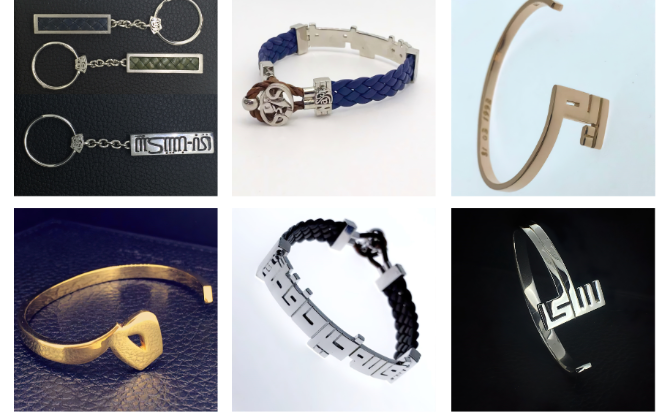

Pieces of Farsi’s jewelry

“People are more into change. They don’t want to get any long-term commitments when it comes to big sets. So, they go and invest their money in a top-notch diamond instead of a piece of jewelry they may not use in 10 years.”

Despite changes in taste and technique, Farsi has sought to maintain the spirit and the essence of traditional Arabian design — even launching his own Nasser Farsi collection in 2015, primarily aimed at the male jewelry market.

“It started as a hobby,” he said. “I turned Arabic calligraphy into jewelry pieces. I have some iconic designs that people can recognize, mainly men’s bracelets. I started designing for women as well, but being a man I wanted something that I could use and I found this gap in the market.”

Timelessness is important. “Jewelers are not salespeople,” Farsi said. “We care about the quality of the stones and the value of the piece, rather than push a simple design that may be worthless in a few years.”

Farsi therefore embraces a little of the old and the new — keeping the classics alive while exploring the creative space that change has opened up. Although the marketplace is fierce, he is impressed by some of the fresh new designers joining the industry.

“It’s beautiful to see a lot of young names coming up. In Saudi Arabia alone, there are tens of people in the business or who have their own lines. It’s also rarer to find a male jewelry designer than a jeweler.”

Pieces of Farsi’s jewelry

In such a competitive marketplace, it is certainly an advantage to have an older, trusted brand backing you up. That is why Farsi is impressed by the number of upstarts achieving success.

“When you say jewelry, people mainly think about the name, the quality and the reliability of whoever they are working with,” Farsi said. “So, to come up with a name and start and make it is something to be proud of. There are a lot of people coming up and they’re making it. It can be quite challenging in the first few years, but they’re making it.”

Luxury items are by definition non-essentials, meaning the jewelry industry’s vitality is to a large extent dependent on purchasing power. Retail-industry research drawn from around the globe suggests customers are becoming more cautious with their spending — a change that retailers themselves must adapt to. Add the COVID-19 pandemic to the mix and the picture gets muddier still.

Lockdown measures forced stores across Saudi Arabia to close temporarily, including Farsi’s branches in Jeddah and Makkah. Besides, with wedding celebrations called off, fewer bridal jewelry pieces are being sold. The crisis has called the jewelry industry’s longevity into question.

“There aren’t as many weddings anymore, so the whole dynamic is fluctuating,” Farsi said. “It’s still not stable, but we are prepared for the worst and working for the best. I do hope I will pass this onto my children.”

There is also limited data available for a detailed industry health check. “Jewelry is an industry that’s barely been tapped into, but it’s taking a big share of cumulative retail reports,” Farsi said. “You don’t see as many detailed or specified reports in the jewelry industry, especially in Saudi Arabia or the Middle East.

Pieces of Farsi’s jewelry

“It’s mainly run in an old-fashioned way in most of the shops. It’s not just in the Kingdom, it’s everywhere. It’s very hard to get information from jewelers.”

The survival of the industry may therefore depend on retailers, manufacturers and governments communicating better — modernizing the business model, sharing expertise, determining best practices and creating regulations collectively.

“We are in continuous meetings with colleagues to try to figure out ways to boost business again around the area and in Saudi Arabia specifically. Everyone is really working hard to implement a change,” Farsi said.

If the industry’s problems are not addressed soon, Gulf countries risk losing a distinctive part of its precious heritage. Fortunately, people like Farsi refuse to let that happen.

“A lot of people in many different fields are working on keeping the culture and the language alive, from artists in the art scene, fashion and jewelry designers, and the whole young generation,” he told Arab News.

“There is this very big hype around putting the culture out there to the world, especially as Saudi Arabia is opening up to the world. There is a pride that everyone has to show the rest of the world.”

__________________________________

Twitter: @CalineMalek