DUBAI: Time was when Turkey pursued a foreign policy devised by an academic turned foreign minister that came to be known as “zero problems” with neighbors.

Even though 10 years is a very short time by the standards of the rise and fall of nations, Turkey’s current diplomatic doctrine does not bear even a smidgen of similarity to what Ahmet Davutoglu had formulated in 2010.

If anything, his former boss, Recep Tayyip Erdogan, is pursuing a policy that has been described variously as “zero friends,” “nothing but problems” and “zero neighbors without problems.”

It is a policy that has now brought US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo to the divided Mediterranean island of Cyprus in an attempt to solve — you guessed it — Turkey’s proliferating problems with its neighbors.

“We hope there will be real conversations and we hope the military assets that are there will be withdrawn so that these conversations can take place,” Pompeo told reporters on the flight to Qatar.

The military assets he referred to belong mainly to Ankara and Athens, but in fact a number of countries are ranged against Turkey over what they view as unmitigated energy piracy aided by gunboat diplomacy.

Turkey has occupied and controls one-third of Cyprus since 1974, when it invaded the north in response to a coup engineered by military leaders in Athens. Now it is embroiled in simultaneous disputes with Cyprus and Greece – a fellow NATO member – over maritime borders and gas-drilling rights.

Fueling Turkey’s great-power ambitions are investments in a domestic arms industry geared to the production needs of everything from warships to submarines, frigates to attack helicopters, and armed drones to light aircraft carriers.

For months now, Turkey has been prospecting for gas and oil reserves in eastern Mediterranean waters claimed by Greece. When it deployed a research ship accompanied by military frigates in August, Greece fired a warning shot by staging naval exercises.

Opinion

This section contains relevant reference points, placed in (Opinion field)

The same month, a minor collision between a Turkish military ship and a Greek navy vessel ratcheted up tensions to a level not seen since a war almost broke out over two Aegean Sea islands in 1996.

As both countries use naval drills in the Mediterranean to reinforce their sovereign claims, the EU has asked Ankara to de-escalate or face sanctions.

US President Donald Trump’s administration has upped the ante by temporarily lifting a decades-old arms embargo on Cyprus. The US embargo had been imposed in 1987 with the aim of facilitating the reunification of Cyprus, but its strategic impact was viewed by many as counterproductive. From Oct. 1, the US will remove blocks for one year on the sale or transfer of “non-lethal defense articles and defense services” to Cyprus.

Karol Wasilewski, an analyst with the Polish Institute of International Affairs, says the US decision has hurt its standing as an honest broker from the Turkish perspective.

“As for Greece, the US cannot provide the carrots that might coax it to start negotiations with Turkey without preconditions,” he told Arab News. “Obviously, it is a good thing that Pompeo has supported peaceful resolution and praised Germany for its de-escalation efforts. But the problem is, the US does not have much leverage.”

That said, Turkish-affairs analysts say the mounting geopolitical tensions give Erdogan yet another tool with which to counter eroding support for his government among rightwing nationalist voters, particularly young conservatives.

More specifically, they say, the authoritarian leader is insisting on an iron-fist approach to Turkey’s disputes with Cyprus and Greece in order to divert attention away from flagging economic growth, high unemployment, a volatile currency, and the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

Regardless of the rationale, Erdogan’s pan-Islamist zeal and neo-Ottoman world view have put Turkey on a collision course with Sunni Arab powers too.

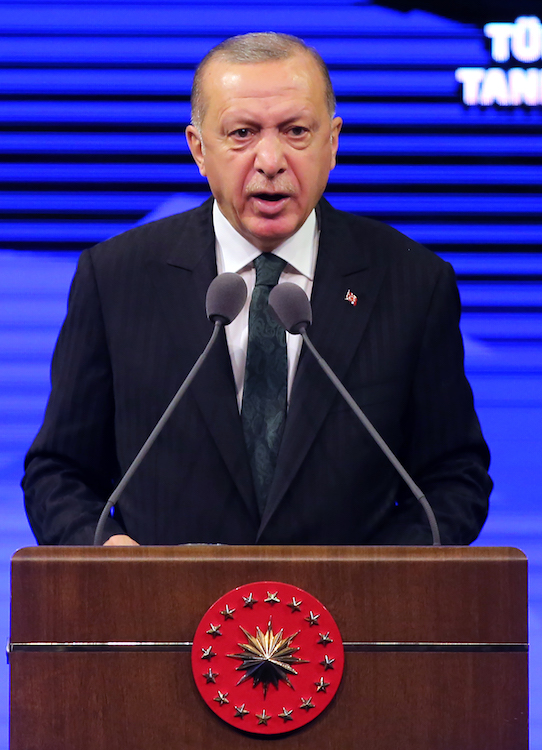

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan speaks during an introductory ceremony for Turkey Insurance at Bestepe People's Convention and Culture Center in Ankara on September 7, 2020. (AFP)

Addressing a recent Arab League ministerial committee meeting, Sameh Shoukry, Egypt’s foreign minister, described Turkey’s military involvement in Libya, Syria, and Iraq as a threat to regional security and stability and appealed for a unified stance.

Reports indicate that in July, Turkey deployed in Libya 25,000 mercenaries, who included 17,000 Syrian militants besides 2,500 fighters of Tunisian, Sudanese, and other nationalities.

More broadly, Turkey’s actions have drawn international attention to the hunt for natural gas fields in the eastern Mediterranean. Along with Turkey, Cyprus, Egypt, Greece, and Israel have staked their claims to the deposits in the seabed.

Recent discoveries off the coasts of Israel, Cyprus, and Egypt have underscored the potential of the area, especially since the announcement of a massive gas field off Egypt’s coast in 2015 boosted these countries’ hopes of becoming energy exporters to Europe.

The newly discovered energy reserves have spawned regional alliances shaped by Turkey’s increasingly antagonistic relations with the EU, Egypt, Israel, and the UAE, not to mention Greece and Cyprus.

An initial agreement involving Greece, Cyprus, Italy, and Israel on the East-Med Pipeline Project morphed into the East-Med Gas Forum with the entry of Egypt, Jordan, and Palestine. Together with Lebanon and Syria, Turkey, a nation of 83 million people, found itself isolated.

******

READ MORE:

Pompeo to visit Cyprus, calls on Turkey to withdraw forces from Mediterranean

EU must consider ‘severe’ sanctions on Turkey, Greece says

NATO sets up talks in search for solution to Turkey-Greece conflict

******

In an apparent bid to reassert its authority, Turkey signed in late July a “delimitation of maritime jurisdiction” agreement with the Government of National Accord (GNA), the Libyan faction in control of Tripoli, and claimed the right to conduct research activities in the disputed waters between Cyprus and Crete.

However, Greece, Cyprus, Egypt, together with France and the UAE, have voiced their objections, saying the Turkey-Libya maritime deal “cannot produce any legal consequences for third states.”

Athens insists that islands must be taken into account in measuring a country’s continental shelf, in line with the UN Law of the Sea, to which Turkey is not a signatory. Ankara believes that a country’s continental shelf should be measured from its mainland, rejecting the argument that offshore islands should supersede mainland claims to as many as 150,000 square kilometers of continental shelf.

For its part, the Cyprus government says its policy of “actively promoting close cooperation” between the region’s countries and “creating synergies for the benefit of all” has resulted in “establishing an attractive environment based on the rule of law.” As evidence, Nicosia has cited the presence of oil majors such as Eni, Total, and Exxon in Cyprus’ Exclusive Economic Zone.

“Turkey on the other hand is the instigator of the current crisis and instability in the eastern Mediterranean,” according to an informal diplomatic note. “Not only does it refuse to engage in negotiations with Cyprus in order to reach an agreement on their respective maritime boundaries, but it persistently violates the sovereignty and sovereign rights of Cyprus, using the protection of the rights of the Turkish Cypriot community ... as a pretext.”

What Greece and Cyprus might lack in military heft, they make up for with diplomatic backing. In the run-up to a special summit of EU leaders on Sept. 24 to 25 to discuss the Cyprus-Turkey crisis, Athens has called for “severe” economic sanctions to be slapped on Ankara for a limited time if it does not remove its military vessels and gas-drilling ships from waters off Cyprus.

And in an unambiguous statement on Sept. 10, the heads of state and government of the southern countries of the EU (Med7), said: “We reiterate our full support and solidarity with Cyprus and Greece in the face of the repeated infringements on their sovereignty and sovereign rights, as well as confrontational actions by Turkey.”

So, what might Davutoglu, the architect of the “zero problems” doctrine, make of Turkey’s “confrontational actions?”

Having broken away last year from Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party to set up his own party and position himself as a potential political challenger, he recently warned that Turkey risks military confrontation in the eastern Mediterranean because it prizes power over diplomacy. “Unfortunately, our government is not doing a proper diplomatic performance,” Davutoglu told Reuters.

-----------------------

Twitter: @arnabnsg