WARSAW: History recently came to life in a manuscript with royal stamps discovered in the archives of SOAS University of London. The historic find? A tantalizing new insight into the journey of the first ruler from the Indian subcontinent to set out for Hajj.

In November 1863, the ruler of the princely state of Bhopal, Sikandar Begum, began the sacred pilgrimage many other sovereigns of her time could not make for fear of losing power — in the 19th century, sea travel from India to Makkah meant long months of absence from the throne. Unlike them, Sikandar was safe. Her Hajj included a mission to compile a travelogue for those who guaranteed her reign.

Sikandar ruled Bhopal from 1844 to 1868. Her forefather, Dost Mohammad Khan, was a Pashtun warrior who, in the early 18th century, gained independence from the declining Mughal Empire and founded a new Muslim state in today’s Madhya Pradesh. Under British rule, for four generations, the country was led by women. Sikandar was the most reform-oriented of them all. She reorganized the army, appointed a consultative assembly, and invested in free education for girls. She was also the first Indian ruler to replace Persian with vernacular Urdu as the official language.

In late January, SOAS librarians came across a title recorded in their archives’ catalogue as “Journal of a trip to Makkah by Skandar Baigam, Ra’isah’ of Bhopal. Bound manuscript in Urdu. Written at the suggestion of Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Marion Durand, 1883.”

“I was really intrigued that such a beautifully bound-in-silk manuscript with obvious royal stamps in its colophon could be linked to such an opaque and short library record,” SOAS Special Collections curator Dominique Akhoun-Schwarb told Arab News.

“It quickly became obvious that there was a bit more story and depth behind the note ‘written at the suggestion of Maj. Gen. Sir Durand,’ when the author was a queen herself, a pioneer, since she was the first Indian ruler to have performed the Hajj and authored an account of her pilgrimage.”

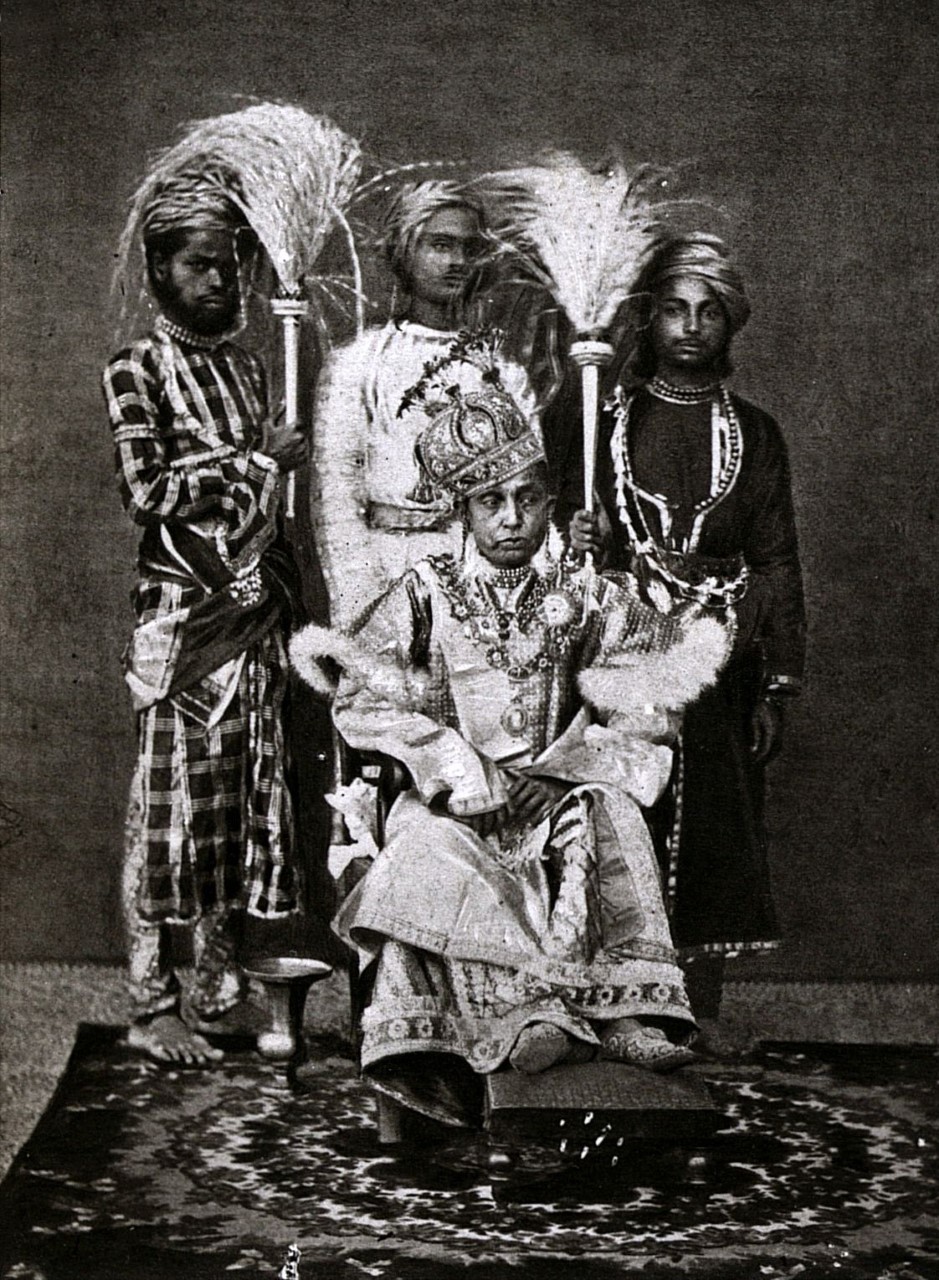

Sikandar Begum ruled the princely state of Bhopal from 1844 to 1868. The photo was published in “A Pilgrimage to Makkah” (1870). (The Asiatic Society of Bombay via AN)

The imprecise note had for decades obscured access to the text for researchers. A deformed transliteration of Sikandar’s name had compounded the issue.

Until the chance discovery a few months ago, all scholarship on the Bhopal ruler’s pilgrimage had to rely on two translations of the text as the original Urdu version was missing for some 150 years. One of them was the abridgment of Sikandar’s account in Persian, compiled by her daughter, Shah Jahan Begum, and included in a state chronicle titled “Taj Al-Eqbal dar Tarikh-e riyasat-e Bhupal.” The other one, “A Pilgrimage to Makkah,” is an English translation by Emma Laura Willoughby-Osborne, wife of Col. John William Willoughby-Osborne, British political agent in Bhopal in the 1860s, which was published in 1870, two years after Sikandar’s death. The two texts are quite different.

In the English version, Sikandar quotes a letter she received from Durand, the British colonial administrator mentioned in the SOAS record, and his wife: “He was anxious to hear what my impressions of Arabia generally, and of Makkah in particular, might be. I replied that when I returned to Bhopal from the pilgrimage, I would comply with their request, and the present narrative is the result of that promise.”

The letter is nowhere to be found in the Persian text.

A preliminary reading by Arab News of the original Urdu manuscript, which has already been digitized by SOAS, reveals that Durand’s letter is mentioned in the very first pages of the text. The correspondence and accuracy of other parts, however, are not immediately obvious.

In the preface to “A Pilgrimage to Makkah,” the translator, Osborne, said that the Urdu manuscript consisted of “rough notes” demanding some arrangement. According to Dr. Piotr Bachtin from the Department of Iranian Studies of the University of Warsaw, who studied female pilgrimage of the era and translated the Persian version of Sikandar’s account, the English translator’s note immediately raises questions regarding Osborne’s interference in the text.

Osborne’s assurance that the only license she had allowed herself had been the “occasional transposition of a paragraph” seems to be an understatement. From the reading by Arab News it appears that the text was heavily edited. As suggested by Bachtin, Sikandar might have been a “reporter” entrusted with a specific task and became an “incidental informer” in the service of the British Empire.

The most interesting aspect of the travelogue, which the newly found manuscript should soon verify, was Sikandar’s political involvement with and open criticism of Ottoman governance in Makkah. One of the most prominent instances of Sikandar’s criticism is the following:

“The Sultan of Turkey gives thirty lakhs of rupees a year for the expenses incurred in keeping up the holy places at Makkah and Medina. But there is neither cleanliness in the city, nor are there any good arrangements made within the precincts of the shrines,” Sikandar wrote, adding that had the money been given to her, she would have made arrangements for a state of order and cleanliness. “I, in a few days, would effect a complete reformation!“

Sikandar’s political commitment is noteworthy. For some reason it is completely missing from the Persian version of her text. “Only in the English translation, she openly criticized both the Pasha and the Sharif of Makkah, going as far as to say that she would have managed Makkah better herself!” Bachtin said, “However, we must remember that her book was commissioned by Sir Henry Marion Durand. For me, this paradoxical dynamic is particularly interesting.”

With the original manuscript now available to researchers, further study should soon reveal how much of the Hajj account was informed by the colonial circumstances Sikandar faced at home, and to what extent it was guided by her own ambitions to be a modern and reformist Muslim ruler.