LONDON: Award-winning contemporary Islamic artist Siddiqa Juma’s path to success was not straightforward.

Juma worked for many years as a graphic designer — a compromise between her creative urges and financial stability. Her parents, she says, wanted her to be a pharmacist, but that was never for her. But the idea of her studying art was never up for discussion.

Juma spent her childhood in Tanzania, East Africa, between Zanzibar — where she was born — and Dar Es Salaam. She recalls those early years, surrounded by “raw beauty,” as being simple, happy and carefree.

Siddiqa Juma worked for many years as a graphic designer. (Supplied)

“There wasn’t this perception that it was dangerous to be outside or that some harm would come to us. We weren’t wrapped in cotton wool,” she tells Arab News.

When she was eight years old, one of her drawings was published in the local newspaper — an early indication of her artistic talent and a moment she still treasures. “That is my earliest recollection of doing art,” she says.

When she was 13, her father’s job at the British Embassy required the family to move to the UK. They settled in London, which is where — after completing her education — she began her graphic design career, laying out a publication called African Events.

It was marriage and motherhood — and the pressure of trying to juggle career and family — that proved decisive in shaping her life as an artist. She describes a watershed moment when her daughter fell ill with gastroenteritis and Juma felt “torn in two” trying to meet work and family commitments. Even though relatives were around to help she found it hugely upsetting and decided to give up her job and devote herself to raising her children.

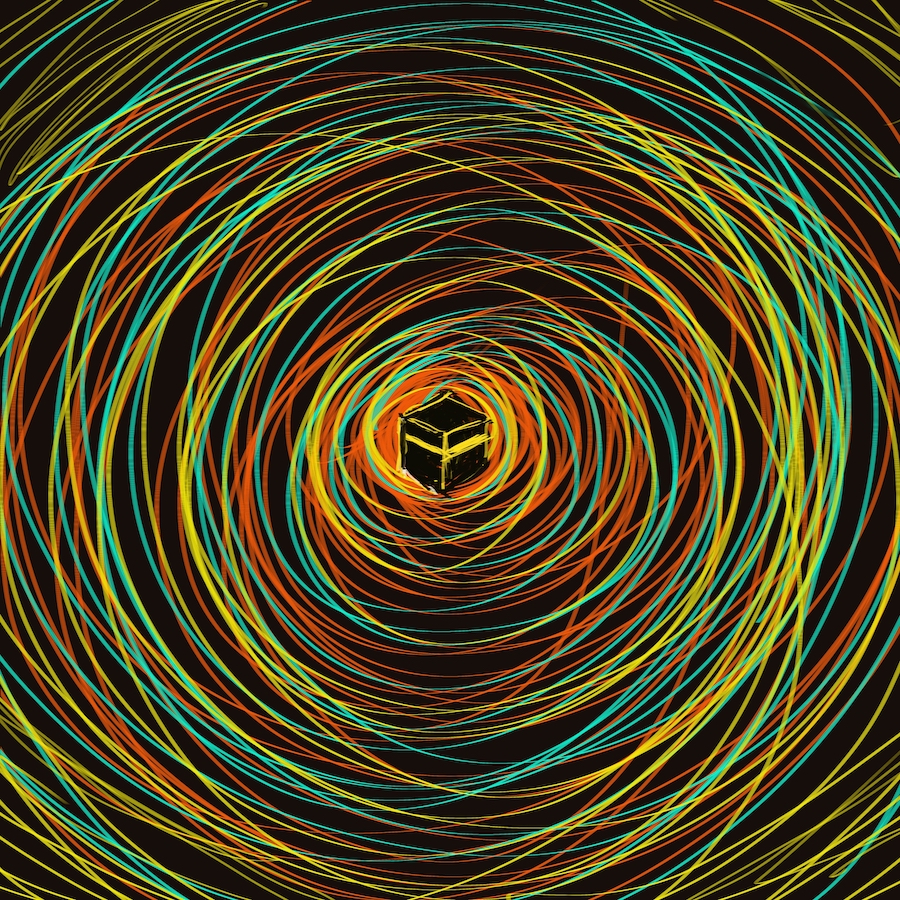

“Digital Kaabah 4” is by Siddiqa Juma. (Supplied)

Although those years were very fulfilling in terms of family, Juma says she felt stifled creatively: “I felt as if there was something I needed to do for myself.”

The turning point came when she wanted to teach her children the Arabic alphabet and found very little in the way of inspiring materials. She also found the TV shows her children were watching lacked content that they could relate to as Muslims. Her solution was to create material herself: She wrote and published a successful educational book and became involved in developing children’s programs.

Juma continues to come up with her own solutions to obstacles. For example, she is keen to use her profile to help other Muslim artists. She notes that while many people are aware of Islamic tourism, finance, modest fashion and food products, Islamic art has not achieved the same recognition. To this end, in January, she launched the online platform IslamicArtPrints.com.

Her own big break as an artist came when one of her paintings was commissioned to hang in the multi-faith room of the Great Ormond Street Children’s Hospital, and she realized there was demand for her work. “I couldn’t believe it,” she says. “That was a ‘light-bulb’ moment.”

Siddiqa Juma addresses the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic in her painting “Hope.” (Supplied)

Two of her best-known pieces are “Make Your Mark” and “Diversity,” both of which — like the majority of her work — express her Islamic faith. “My faith is my life and my compass for living,” she says. She has also produced a number of works focusing on the Hajj, many of which were featured at an exhibition in Jeddah — “I was paid to go to Hajj! It was literally my paintings that took me to Makkah,” she told UK website Change The Script in 2018. “It was a very emotional time.”

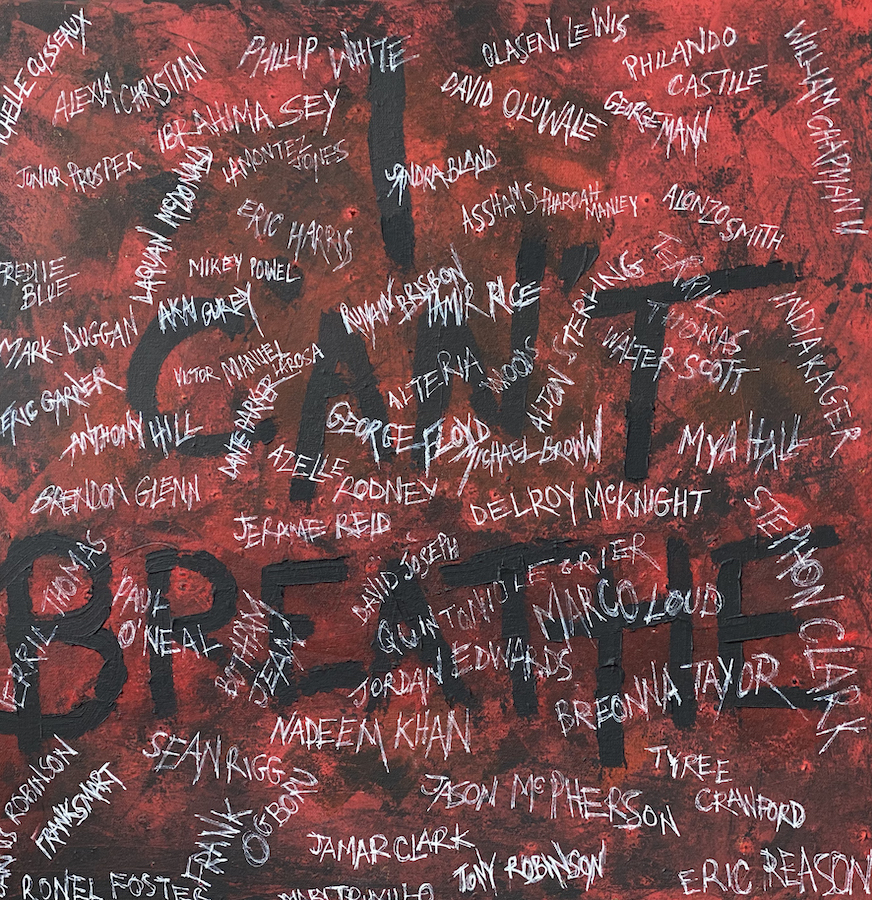

Her work is usually conceptual and abstract — rather than a literal interpretation of Islamic themes, and she is also known for using her art as a response to critical events, including the London and Manchester bombings, the New Zealand mosque massacre and, most recently, the killing of Floyd George. Her piece “I Can’t Breathe” pays tribute to black victims of police brutality. The proceeds from that painting will be donated to an anti-racism cause.

“I Cant Breathe” is by Siddiqa Juma. (Supplied)

“Sometimes events wake you up,” she says. “You can go through life without really examining that being black can mean being disadvantaged in so many ways, but this really upset me.”

Another seismic event, of course, is the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, which Juma addressed in her painting “Hope.” She believes the global crisis has given people a chance to pause and reflect on some of the things that are out of balance in our world.

“I hope things don’t return to ‘normal’,” she says, explaining that she sees the pandemic as an opportunity to ensure a “more compassionate outlook” is given greater prominence.