SURABAYA: Along the K.H. Mas Mansyur Street in Surabaya’s Arab Quarter, crowds of shoppers during Ramadan were conspicuous this year by their absence.

There were no throngs of people crowding around the Ramadan bazaar food stalls selling famous Arab delicacies.

“With the social restrictions in place due to the coronavirus disease (COVID-19), we did not have such festivities this year,” said Abdullah Albatati, a resident of the Arab Quarter and head of the Surabaya Arab Community.

“Some of the food stalls served only local customers. The Middle Eastern eateries were open for takeout food, so people just came, bought and left,” he added.

One of the most captivating places in Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-largest city, the Arab Quarter, situated to the north of Chinatown, offers vibrant evidence of its origins as an Arab trading post.

The shops lining the streets and alleys there bear names such as Nabawi, As Salam, Khadija, Al-Huda, Al-Hidayah, and Zamzam, and sell perfumes, dates, pistachios, prayer beads and other paraphernalia.

An alleyway in the Arab Quarter that leads the ancient mosque and tomb of Sunan Ampel one of the nine propagators of Islam in Java, of whom the area is named after. (Photo: Nunung Tejo Purnomo)

One of the oldest stores on the street is Salim Nabhan, a bookstore and publisher of Muslim literature established in 1908. It still prints some books in Arabic for Islamic boarding school students who are learning the language.

Trader Abdurrahman Hasan Al-Haddad, who owns Zamzam, is a fifth- or sixth-generation Arab, as is Albatati. Their ancestors migrated from Hadhramaut (in Yemen) in the 19th century to towns along the northern coast of Java Island and other islands across the then Dutch East Indies archipelago to settle in Surabaya.

The Arab Quarter, which comes under the sub-district of Ampel in the Surabaya district of Semampir, has the largest concentration of Arabs in Indonesia.

Stores with Arabic name in Arab Quarter’s Sasak Street. (Photo: Nunung Tejo Purnomo)

They comprise the majority as opposed to the other ethnic groups such as the Javanese, the Madurese from Madura Island, Bugis from Sulawesi Island, or the Malays who migrated to the region and whose descendants now live in Ampel.

“As one of the ethnic groups in Indonesia, we still maintain our Arab roots, but it never makes us feel any less Indonesian, Javanese or Surabayan,” said Albatati, as he chatted with his friend Al-Haddad on the latter’s decision to relocate his shop.

They speak in a mix of three languages — the country’s lingua franca Indonesian, Javanese and Arabic.

Shops selling Muslim paraphernalia that lined the streets and alleys in the Arab Quarter. (Photo: Nunung Tejo Purnomo)

“It is typically spoken here,” said Albatati. “There are some Arab words which have been integrated into the Javanese dialect and into Indonesian and they are spoken not just by the Arabs but also by the other ethnic groups in the quarter,” he said.

According to Huub de Jonge, Dutch anthropologist and Indonesianist from the Netherland’s Radboud University Nijmegen, more than 95 percent of the Arab community in Indonesia trace their roots to Hadhrami tradesmen who migrated there, married local women, and formed families who spread out.

FASTFACT

Indonesia's Arabs

More than 95 percent of the Arab community in Indonesia traces its roots to Hadhrami tradesmen of Yemen who migrated there

The rest of the Arabs in Indonesia originated from Hijaz in Saudi Arabia.

This is not known to many of the non-Arab communities in Indonesia, said de Jong, despite the fact that many Arab descendants had made their mark in Indonesian society as government ministers and officials, successful businesspeople and as nationalists who fought against Dutch colonialism.

Some shops are closed in the area as they abide by the large scale social restrictions measure to curb the spread of the coronavirus in Surabaya. (Photo: Nunung Tejo Purnomo)

The Arab community is the second-most important minority group of foreign origin in Indonesia, he told Arab News.

In his book on the Hadhrami Arabs in Indonesia, “Mencari Identitas: Orang Arab Hadhrami di Indonesia (1900-1950),” meaning Searching for Identity: Hadhrami Arabs in Indonesia (1900-1950), de Jonge writes that the nationalist Abdul Rahman Baswedan, the grandfather of the current Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan, hailed from the Arab Quarter in Ampel.

Abdurrahman Hasan Al Haddad (in white cap) and Abdullah Albatati in front of Al Haddad’s store Zamzam. (AN Photo/Ismira Lutfia Tisnadibrata)

As a journalist turned politician in the early decades of the 20th century, Abdul Rahman Baswedan was critical of the social-class hierarchy within the minority group and its insularity.

The elder Baswedan was instrumental in the establishment of the Indonesian Arab Union in 1934 and championed the Hadhrami community’s integration with the wider society, urging his community to start referring to the country they lived in as their homeland.

The Arab community in Indonesia in the past, said de Jong, had a tendency to flock together and this was mainly due to the Dutch East Indies colonial government’s policy to form a ghetto for the Hadhrami immigrants arriving in port cities across the archipelago.

Abdullah Albatati in front of Hotel Kemadjoean, one of the oldest buildings in the area owned by the Al Irsyad, a mass Muslim organization that was established in 1914. (AN Photo/Ismira Lutfia Tisnadibrata)

“It was like a trade restriction policy, to restrict their mobility and to curb Arab traders from spreading Islam as they did not like the Muslims to be united for political reasons, given that at the time, there was a global pan-Islamism movement,” de Jong said.

In 1920, the colonial government allowed Arabs to move out of the ghetto, which gradually led to many Arabs in other places moving out, such as in the Pekojan area in Jakarta, which unlike Ampel in Surabaya, no longer has a concentrated Arab community.

In Surabaya’s Arab Quarter, however, the community chose to stay on, de Jonge added.

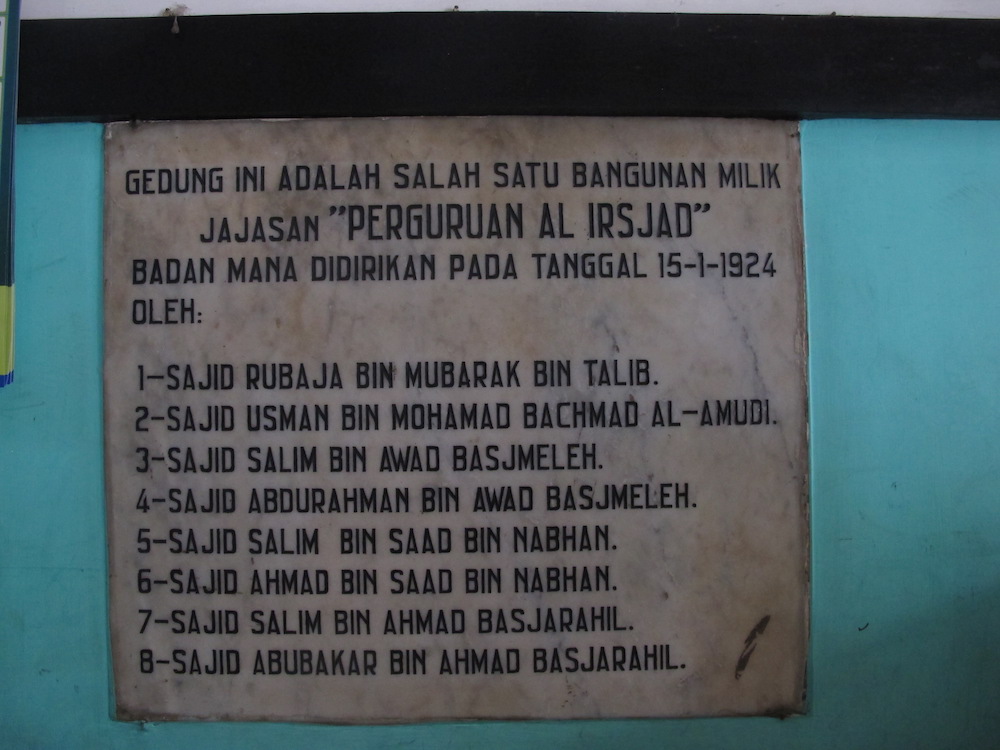

An inscription inside the hotel explaining the building is owned by an education wing of Al Irsyad established in 1924 and names of the wing’s founders. (AN Photo/Ismira Lutfia Tisnadibrata)

The other predominantly Arab enclave in Indonesia is in Palembang in South Sumatra province on the banks of the Musi River.

The Arab community, said de Jong, remained a strong entity that kept its customs alive.

Albatati said the burial customs, for example, were funded by a cemetery waqf from Arab families, assigning plots of land as burial sites for their descendants, blood relatives, and those who became part of the community by marriage.

A whiteboard in front of the hotel used to announce a death that occurs in the community, detailing the name of the deceased, families, schedule for praying, and burial of the deceased. (AN Photo/Ismira Lutfia Tisnadibrata)

According to de Jong, Arabs who stayed back in the quarter are more conservative compared to those who left, although when compared to the Arab communities outside of Java, they are more exclusive since they assimilated with the locals and other ethnic groups. However, they too “continue to retain their traits which make them stand out,” de Jong added.

Zeffry Alkatiri, author and historian from Universitas Indonesia’s School of Cultural Studies, said that there was a difference between the two streams of Arab migrations that came to Indonesia.

“There is a general perception that the Arab diaspora in Indonesia are descendants of those who migrated from Hijaz, when there are actually significant differences between the two regions (Hadhramaut and Hijaz),” he told Arab News.

Some shops are closed in the area as they abide by the large scale social restrictions measure to curb the spread of the coronavirus in Surabaya. (Photo: Nunung Tejo Purnomo)

“It was obvious from (the reaction of) a high-ranking government official who attended a convention on the Hadhramis in Indonesia a few years ago: He could not tell that there were distinctions in the Arab communities in Indonesia.”

What makes the Arabs distinct from the others, said Alkatiri, was the trading ecosystem in Ampel. “Trade and businesses that have run for generations form the core that keeps the Arab Quarter alive.”