RIYADH: Throughout history, the Arabian Peninsula has suffered from several pandemics due to its strategic location, bringing traders and pilgrims from around the world.

The Spanish influenza of 1918 emerged as the world was recovering from the First World War, leaving extensive, unexpected effects.

According to recent studies on the devastating pandemic, nearly 500 million people around the world were infected. Between 50 and 100 million people perished.

1918 was known in the Arabian Peninsula as the “Year of Mercy” and “Year of Fever” — a reference to the disease’s high fever, according to Guido Steinberg, a German Arabist, who has written two articles on the impact and collective memory of the flu in Syria and the peninsula.

It took the flu a few months to wipe out towns and villages and dramatically decrease the populations in the Arabian Peninsula. People checked homes only to find the entire household dead.

Running out of coffins, people started to take out their doors and use blankets to transfer dead bodies to the mosque for burial.

With infected people not lasting more than two days, many volunteered to wash the dead, dig graves and bury them as gravediggers were exhausted. Some people dug all day except during prayer times, which was considered their break.

In Abdul Rahman Al-Suwayda’s book “Najd in the Recent Past,” he said that the fight against the pandemic was mainly based on isolating patients in homes and places outside the town or the walls of the city.

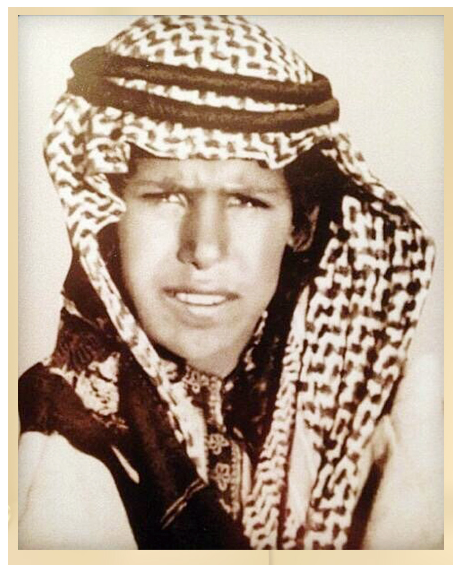

Prince Turki, the first son of King Abdul Aziz.

He said that healthy people may have been given emergency vaccinations.

“They take pus from patients and vaccinate the rest of the people in primitive ways, thereby limiting the spread of the disease. Herbs and medicinal formulations were some of the methods used by the grandparents in fighting diseases,” Al-Suwayda said.

“In the patient’s 40-day recovery from an epidemic disease, and with the beginning of recovery, women collect parts of all the food available in the town and cook it in one pot called ‘Al-Qiru,’ where the patient eats and drinks the cooked broth as a kind of precaution.”

HIGHLIGHTS

• Nearly 500 million people around the world were infected. Between 50 and 100 million people perished.

• 1918 was known in the Arabian Peninsula as the ‘Year of Mercy’ and ‘Year of Fever’ — a reference to the disease’s high fever, according to Guido Steinberg, a German Arabist.

• It took the flu a few months to wipe out towns and villages and dramatically decrease the populations in the Arabian Peninsula. People checked homes only to find the entire household dead.

According to Al-Suwayda, people believed that if the patient ate food not cooked in Al-Qiru, they would experience complications and relapse. The pot contained a collection of camel, lamb and goat meat.

In Paul L. Armerding’s book “Doctors for the Kingdom: The Work of the American Mission Hospitals in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,” the founding King Abdul Aziz had a prominent role in the fight against this pa ndemic, where he called doctors to treat the infected.

Quarantine in the US in 1918.

“Dr. Paul Harrison’s second invitation to visit Riyadh arrived with urgency. In the winter of 1919, the influenza epidemic spread around the world, claiming many lives, and the vast expanse of the Arabian desert did not stop the epidemic from reaching Riyadh,” said Armerding.

When Dr. Harrison arrived in the capital, King Abdul Aziz had lost his eldest son Turki and his wife Jawhara bint Musaad. Despite this, Harrison was able to bring comfort and assistance to many infected people, most of whom were cured.

“Ibn Saud was standing in a small, modest room, and he met Paul with a warm handshake,” said Armerding.

“When King Abdul Aziz greeted him, Ibn Saud … explained that he had requested a doctor not to take care of his health or that of his family, but for the need of his people, and that he had allocated a house nearby to be a hospital, and he wanted his people to be treated for free.”

The epidemic spread from Makkah to the south of Najd, then reached the north and east of the Arabian Peninsula.