LONDON: Arabic calligraphy has become a very progressive and sought-after form of art, according to renowned artist Taha Al-Hiti.

In celebration of 2020 being the Year of Arabic Calligraphy in Saudi Arabia, Arab News spoke to the Iraqi artist to get his take on the unique art.

He pointed out that Arabic letters and their forms were very distinctive in the way they were shaped.

“I have found a relationship between all the elements of the letter, which I later found out were linked to the human body and the golden section and all these proportions of beauty, which have just enchanted my eyes since a very young age,” he said.

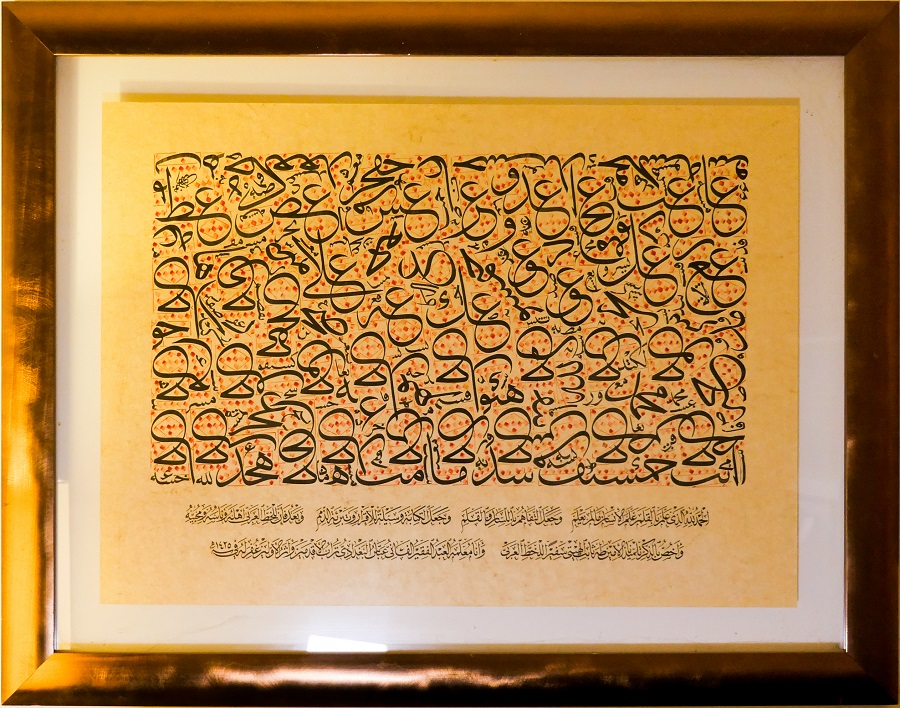

An example of work by artist Taha Al-Hiti. (Supplied)

Arabic letters, he added, were designed to emulate the human body, animals and nature in general. The “golden section” (also referred to as the golden ratio or mean) appears in geometry, art, architecture and other fields that are designed to make some of the most beautiful shapes.

Several renowned buildings and artworks apply the golden ratio, such as the Parthenon in Greece, Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man” and the “Mona Lisa,” Salvador Dali’s “The Sacrament of the Last Supper,” as well as UNESCO World Heritage Sites such as the Great Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia and Naqsh-e Jahan Square in Iran, among others.

Al-Hiti noted that Arabic letters had their own components of the human body and were “based on a very organic way of building.” They are referred to as either “the chin, neck, body, or chest of the letter,” and so on and were also grouped into families.

An example of work by artist Taha Al-Hiti. (Supplied)

“For example, the letter Alif (or A in English) in calligraphy is written in a straight, vertical line. But in Arabic calligraphy, it is a straight line leaning slightly forward with a chest that’s protruded forward and the lower part is going backwards, just like the human posture,” he said.

Other examples are the letter Ain (or Aa in English) which takes the form of the eyebrow (or Hajjib in Arabic) and the letter Haa and Kha and Jeem (H, Kh, and J) which are from the same family and are shaped like an ear of a horse.

A graduate of architecture from the University of Baghdad in Iraq, Al-Hiti, was pressured into pursuing a medical degree or one of a scientific nature by his father.

“My dad was a doctor and he suggested I became a doctor, and I said no forget it, I want to be an artist. I thought architecture had got a lot of mathematics and science, as well as arts,” he added. This enabled him to combine his passion for calligraphy and Islamic arts, while also pleasing his family.

Arabic calligraphy has become a very progressive and sought-after form of art. (Supplied)

Al-Hiti was drawing his name and his parents’ before he learnt to read.

“I used to draw the names, not knowing which one was my name or which was my dad’s or being able to read them. I used to just replicate the shapes that I saw, in enchantment of the beautiful letters and then it was always present with me.”

He compared Arabic calligraphy to any other art form. “I suppose, like all sorts of arts or skills, calligraphy predominantly is a skill mixed with a good or variable bit of talent, but it’s a skill like playing the piano or sketching in pencil, these are all skills that you acquire through practice. Calligraphy requires a lot of practice, mixed with the talent and character of the calligrapher.”

He said each calligrapher’s work was based on the teachings of their “master,” ranging from various countries including Iraq, Iran, Morocco, and Andalusia in Spain, which has deep Islamic artistic roots.

Al-Hiti noted that Arabic letters had their own components of the human body and were “based on a very organic way of building.” (Supplied)

“Calligraphy is an art that is inherited by generations that teach it to each other, so you could tell which master or if it was from a Baghdad, Moroccan or Turkish school. All the different calligraphy forms are developed in different nations of the Islamic world,” he added.

Comparing the different types of calligraphy, Al-Hiti said that Arabic calligraphy was always drawn horizontally, as opposed to, for example, Japanese or Chinese calligraphy, which was drawn vertically, and also used different techniques, inks and pens.

However, he said he aspired “to find a modern form of doing calligraphy or compositions” and “started forming vertical letters for mosques’ minarets,” and had done many successful trials, one of them 90 meters high.

“It’s the versatility in breaking the rules and how good you are in breaking those rules and coming up with something new, not necessarily replicating traditional forms, but no harm in sticking to the original rules of calligraphy as well.

“I think it’s changing for the better, there’s more interest, and the proof is this interview, that you want to convey more about this beautiful art to the public, and that is a beautiful thing.

“And the more you look at it, whether you’re an Arab or non-Arab, whether you can read it or not, you will actually find the rhythm in it, you will find the balance, you will find the harmony, you will find the contrast,” Al-Hiti added.