DUBAI: Practiced for hundreds of years, Arabic calligraphy is being acknowledged on a grand scale in 2020.

Saudi Arabia has declared 2020 as the Year of Arabic Calligraphy, and UNESCO has registered Arabic calligraphy on its Lists of Intangible Cultural Heritage.

“Like many of my colleagues, I was thrilled that UNESCO recognized its historical importance for the heritage and culture of Islamic lands,” Prof. Tanja Tolar, a specialist in medieval Islamic art, told Arab News.

The word Kufic is derived from the southern Iraqi town of Al-Kufa. (Getty)

“Many consider calligraphy as quintessentially Islamic, the cultural identity of the Muslim world,” said Tolar, who teaches the history of Arab painting at London’s School of Oriental and African Studies.

“If you ask any student of Islamic art what attracted them to the study of this subject, they often specify the beauty of Arabic calligraphy.”

Kufic script is one of the most recognizable and exquisite scripts of Arabic calligraphy. It is so revered and foundational that medieval Egyptian encyclopedist Al-Qalqashandi once declared: “The Arabic script is the one which is now known as Kufic. From it evolved all the present pens.”

Developed between the seventh and 10th centuries, the Kufic script is considered one of the oldest forms of Arabic calligraphy.

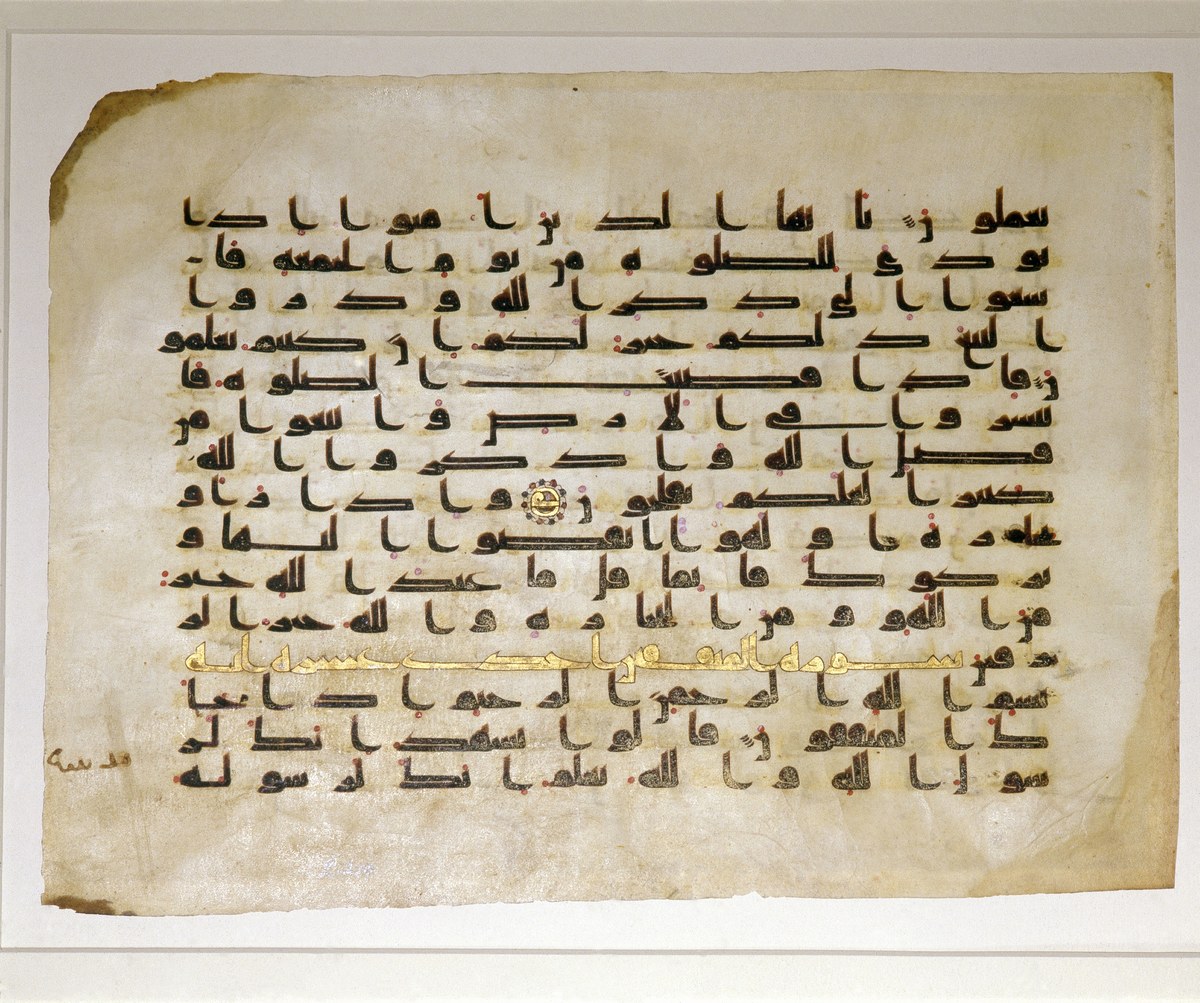

The Kufic script was notably used for writing Qur’anic manuscripts. (Getty)

According to scholars, its name is derived from the southern Iraqi town of Al-Kufa — a powerhouse of Arab scholarship and cultural learning in the medieval era — where this script was created.

For a long time, the Kufic script — which reached its peak by the ninth century — was notably used for writing Qur’anic manuscripts.

Its leaves would have been initially produced from calves’ and goats’ skin, also known as parchment.

The elaborate script also touched the surfaces of coins and inscriptions on tombstones and buildings.

Tolar said one of the earliest examples of the Kufic script can be found in the form of a 240-meter-long Qur’anic inscription in Jerusalem’s Dome of the Rock, dating back to 692 AD.

Stylistically, this bold, angular and rather strict form of calligraphy is characterized by short vertical and elongated horizontal strokes.

This form of calligraphy is characterized by short vertical and elongated horizontal strokes.

“An angular script such as Kufic is so popular because it’s clear to read,” said Tolar. “We need to remember that often text was written to be read out loud, and legibility was of high importance. The writing gives a specific uniformity to the visual appearance of the script.”

Because of its signature elongated style, this kind of script was usually carried out in a landscape format, where verses dominated the space in a well-ordered fashion.

“Qur’ans in Kufic are organized in blocks which would see words of the text break between the end of one line and the beginning of the other,” said Tolar.

A famous example that demonstrates the Kufic script in its classical sense is the Blue Qur’an, a sumptuous ninth-century manuscript that was probably produced in Tunisia.

Elongated verses painted in gold have been set against an indigo-dyed parchment, creating a magnetic contrast.

Historically, calligraphers used the reed (or kamish) pen as a key writing utensil, dipped in black or red ink.

A famous example that demonstrates the Kufic script in its classical sense is the Blue Qur’an.

On executing the perfection of this time-consuming form of writing, Tolar said the calligrapher would need to embody “patience, discipline and stamina. The hand needs a lot of practice to produce all letters the same way.”

Saudi calligraphy artist Abdulaziz Al-Rashidi is a great admirer of the aesthetics of this script, as one can see in his detailed and contemporary works.

“When I was 7 years old, it was the pen that I admired, not exactly calligraphy. I didn’t know anything about calligraphy, but from a distance I loved watching calligraphers write,” he told Arab News.

Al-Rashidi studied the intricacies of Arabic calligraphy at Madinah’s King Abdul Aziz University for four years under the supervision of notable calligraphy professors.

“You can’t imagine the state of happiness I was in when I held my first pen. I’ve learned that you need to practice daily and can’t execute this kind of art without having patience,” he said.

Coin with Kufic inscription.

“For example, if you were to write the head of the ‘waw’ letter, you’ll encounter 15 rules of writing it. And if in a second your mind drifts away, you’ll lose its shape — it’s done.”

As with any art form, the Kufic script evolved over time. Helpful linguistic markers were introduced, and numerous styles of the script emerged in Iran, Andalusia and North Africa.

“In general, the Kufic script was the first of Arabic calligraphy. It has more than 500 types, some of which have remained, disappeared and are being developed,” said Al-Rashidi.

Due to the arrival of more cursive Arabic scripts, use of the Kufic script declined in the 12th century. But “it never lost its visual appeal,” Tolar said.