ABU DHABI: Less than two months since an unhappy year for the Arab region’s migrants and refugees came to an end, the omens of things to come are far from good.

According to the latest “Situation Report on Migration in the Arab Region,” prepared by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in collaboration with various UN agencies, displacement and migration are two prominent trends at the beginning of 2020. Particularly — and unsurprisingly — in countries with ongoing wars.

An overwhelming majority of Arab countries endorsed the Global Compact for Migration (GCM) at the UN General Assembly in December 2018, voting to adopt its principles in national legislatures.

Subsequently, the number of migrants and refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea was found to have plunged in 2018 to almost a tenth of what it was in 2015.

However, the reality of the region’s migrant and refugee situation belies the hopes raised by the adoption of the GCM.

In Libya, for example, there was a steep deterioration last year in the living conditions of migrants and refugees stranded in the unstable North African country.

FASTFACTS

29m - An estimated 29 million people have migrated from Arab countries since 1990.

1/2 - Almost half of the people who migrated stayed within the Arab region.

9.1m - Refugees who have sought protection in the Arab region include 3.7 million under the mandate of the UN Refugee Agency and 5.4 million registered with UNRWA.

14.5% - The number of migrant workers in 18 Arab countries stood at 23.8 million in 2017, representing 14.5 percent of all migrant workers globally.

The country’s protracted civil conflict has not only caused massive displacement within its borders, but also means it has become a dangerous place for economic migrants from sub-Saharan Africa wishing to travel to Europe.

World leaders have just pledged in Berlin not to interfere in Libya’s civil conflict and to uphold a UN arms embargo, but only time will tell if that promise will be honored.

In Syria, meanwhile, the humanitarian situation in Idlib — the last stronghold of opposition forces and a safe haven for millions of internally displaced persons (IDP) — remains shaky as Russian-backed regime forces press on, despite mounting civilian casualties.

In Yemen, a peace opportunity was missed in early 2019, and there has been no let-up since in the fighting between government forces and the Houthi militia, who control the capital Sanaa and the northern highlands.

The country currently hosts between 2 million and 3.5 million IDPs and another 1.28 million returnees, in addition to 279,000 migrants and refugees — almost exclusively from Somalia and Ethiopia — for whom the country is a short-term way station, not a final destination.

Lebanon is in the grip of a wide- ranging crisis, too. People at the bottom of the economic ladder, including 1.5 million Syrian refugees and almost 500,000 Palestinian refugees, supplement their meager incomes with handouts from aid agencies.

Even before the protests erupted in Lebanon in October last year, a UN vulnerability assessment report for refugees in the country, carried out in early 2019, made grim reading.

Illustration courtesy of International Organization for Migration (IOM)

It said about 73 percent of Syrian refugees in Lebanon were living below the poverty line — up from 69 percent the year before, and considerably higher than the estimated 28 percent of Lebanese in the same situation.

Of course, migration and displacement have long shaped the Arab region, with countries simultaneously acting as points of origin, transit and destination.

However, in recent years, the distinction between voluntary and forced migration has become blurred as political crises and civil conflicts — viewed as the chief causes of human displacement — have proliferated.

“The challenge today is to put in place policies that will ensure successful and true integration while benefiting both the countries of residence and origin,” Laura Petrache, a senior adviser at Migrant Integration Lab, told Arab News.

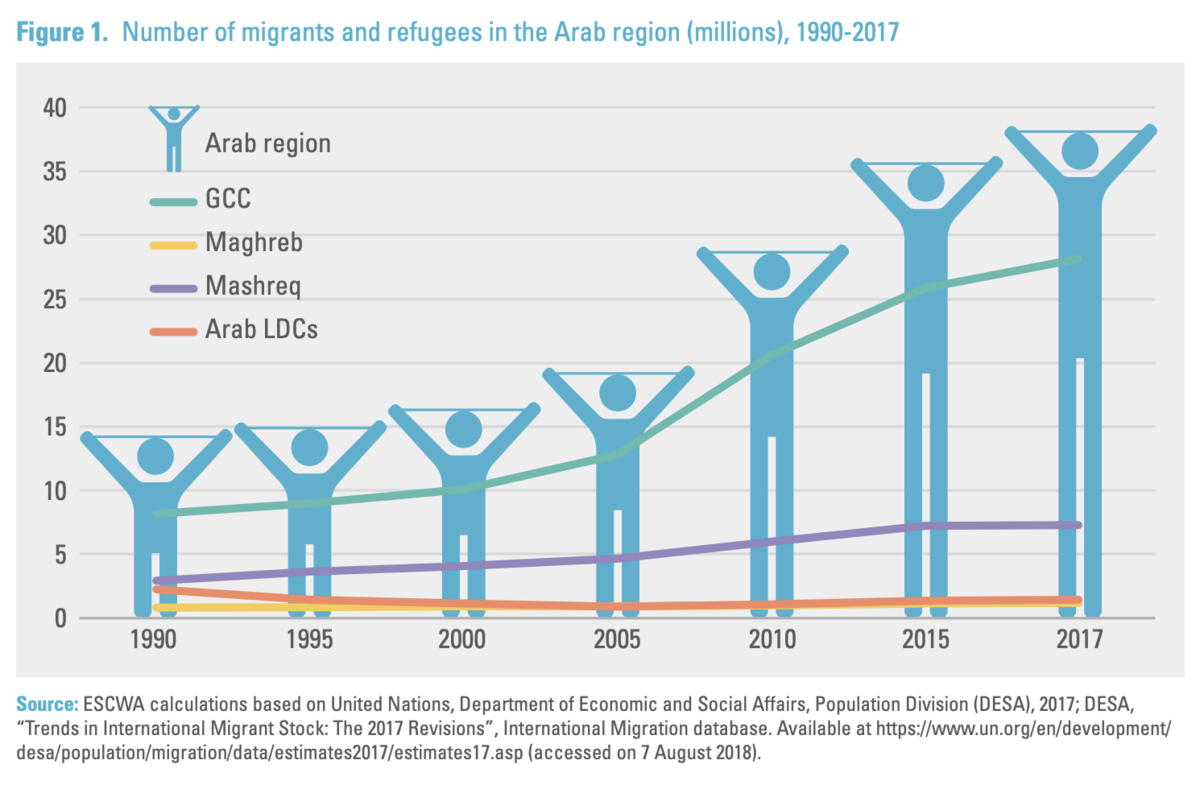

According to UN reports, the number of migrants and refugees originating from the Arab region reached 29 million in 2017. Almost half of them remained in the region. Overall, the number of migrants and refugees as a proportion of the total population of the Arab region has risen steadily over the past three decades.

In 2018, around 80 percent of the region’s refugees originated in the Levant, mostly on account of the Syrian conflict.

The number of migrants and refugees crossing the Mediterranean Sea was found to have plunged in 2018 to almost a tenth of what it was in 2015. (AFP)

Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Syria and Sudan are among the top 10 Arab destinations for migrants and IDPs owing to conflicts in the neighborhood. Apart from Lebanon, all of those countries have witnessed an increase in the number of refugees and migrants within their borders since 2015.

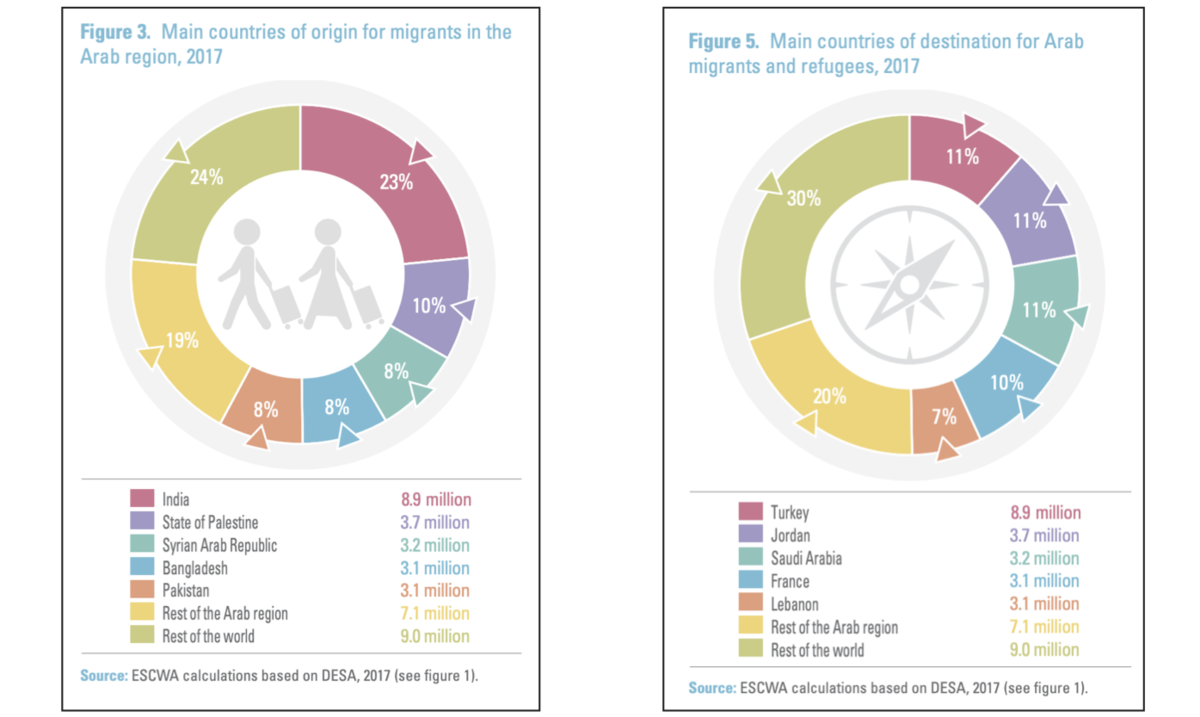

After Turkey, Jordan was the second-most-popular destination country for refugees and migrants from the region, with Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and the UAE also reporting significant numbers. Iraq was the only country that saw its national refugee and migrant population decrease.

What the latest reports confirm is that migration in the Arab world not only has multiple drivers — socio-economic pressures, political instability and environmental degradation — but also complex patterns and trends.

Take the Gulf and the Levant regions. They attract different kinds of migrants because their levels of stability, security and development are not comparable.

While Libya, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen are plagued by conflict, violence, corruption and divisions in both society and polity, GCC member countries are leading the way in groundbreaking ideas and investments, building cities of the future and attracting talent from across the world.

Illustrations courtesy of International Organization for Migration (IOM)

The migrant population in the GCC countries swelled from 8.2 million in 1990 to 28.1 million in 2017 — a substantial rise compared with figures for other parts of the Arab region.

Around 27 percent of global remittance outflows in 2017 reportedly came from the Arab region, estimated at $120.6 billion, and almost all of that (98.9 percent or $119.3 billion) came from GCC countries. According to the IOM’s report, the top remittance-sending countries were the UAE (at $44.3 billion) and Saudi Arabia (at $36.1 billion).

Under the circumstances, it is difficult to see meaningful, positive change for migrants happening any time soon in the Arab region, with the possible exception of the GCC.

“Migration policy making should move away from assimilationist frameworks,” Petrache, of the Migrant Integration Lab, told Arab News. “Instead, the policy emphasis should be on working with countries of origin to achieve sustainable integration — and re-integration in the case of return immigration.

“The policies should take into consideration the potential for win-win solutions using and developing the capability of the migrants to make a positive contribution to local host communities,” Petrache said.