DUBAI: Calligraphy, a practical means of communication, has evolved into a distinctly cultural proponent that is as contextual as it is decorative. Multifaceted and complex, calligraphy is a tradition that simultaneously reveals and shrouds layers of history, meaning and cultural value.

Though calligraphy dates back to Sumerian cuneiform around 3,500-3,000 B.C., the spread of the Islamic religion from the 7th century saw a more definable form of Arabic calligraphy that gave birth to numerous standardized and regional styles.

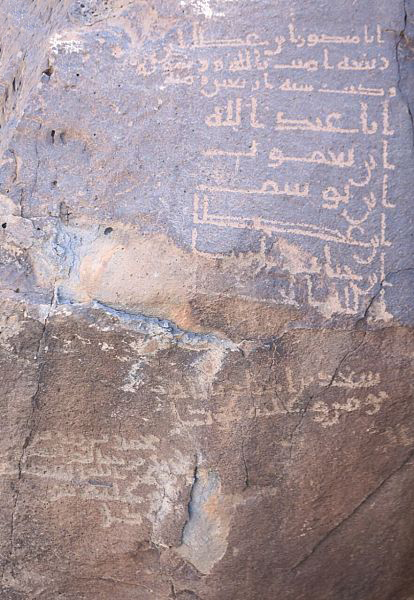

Madani, one of the oldest Arabic fonts, was named after Al-Madina Al-Muwara in Saudi Arabia. (SPA)

Each style contains a unique function, time stamp, patron, audience, context and place of origin — details which are discerned by analyzing, for example, letters such as Alif or Laam.

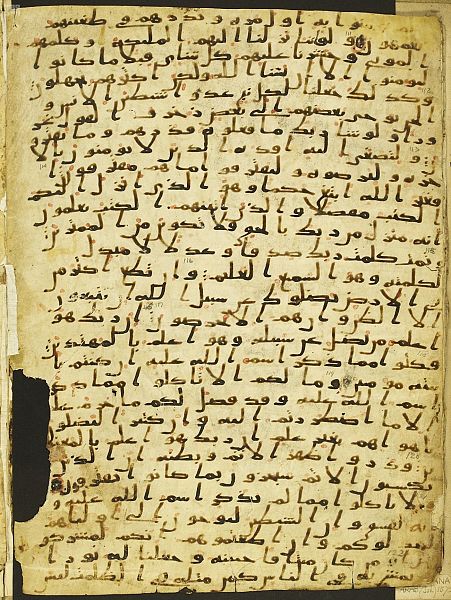

However, first and second Hijri century calligraphy leaves ample room for the adventurous scholar. Many fragmented surviving documents exclude era indicators such as colophons, dates and authors, relying instead on carbon-14 dating to extract a document or object’s investigative launch point, or resources like Ibn Al-Nadim’s 10th-century “Kitabh Al-Fihrist,” which reveals the four first calligraphic varieties to be Makki, Madani, Basri and Kufi.

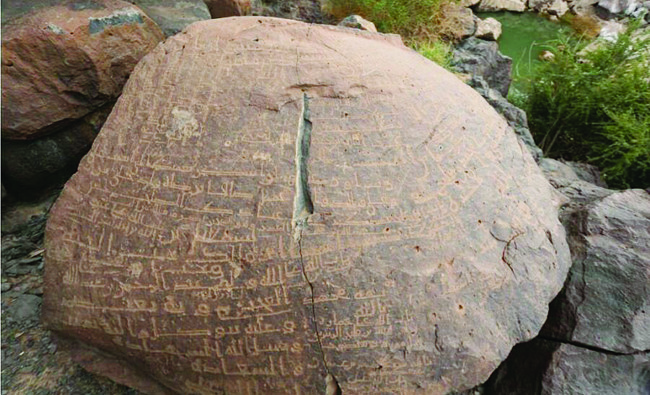

Madani was used to transcribe the Holy Qur’an and Al-Sunnah, in addition to correspondence between kings. (SPA)

With no clear linear progression and strong stylistic similarities, in the 18th and 19th centuries the various monumental, angular and unpointed Arabic scripts typically used for writing the Qur’an in the first to third Hijri centuries were grouped under the blanket term “Kufic.” Makki and Madani were further linked under “Hijazi” — early handwriting from western Arabia — that in recent years Saudi Arabia has sought to protect.

“Madani is one of the oldest Arabic fonts that was named after Al-Madina Al-Muwara in Saudi Arabia, where it first emerged and was used to transcribe the Holy Qur’an and Al-Sunnah, in addition to correspondence between kings,” explains Fadhel Al-Ali, Sharjah Calligraphy Museum assistant curator. It is understood as a localized variant of the pre-Islamic Jazm script, borrowing from Himyar Musnad cursive and Nabatean script from the regions of southern Syria and Jordan, northern Arabia and the Sinai Peninsula.

Madani is characterized by the integrity and flexibility of its letters. (SPA)

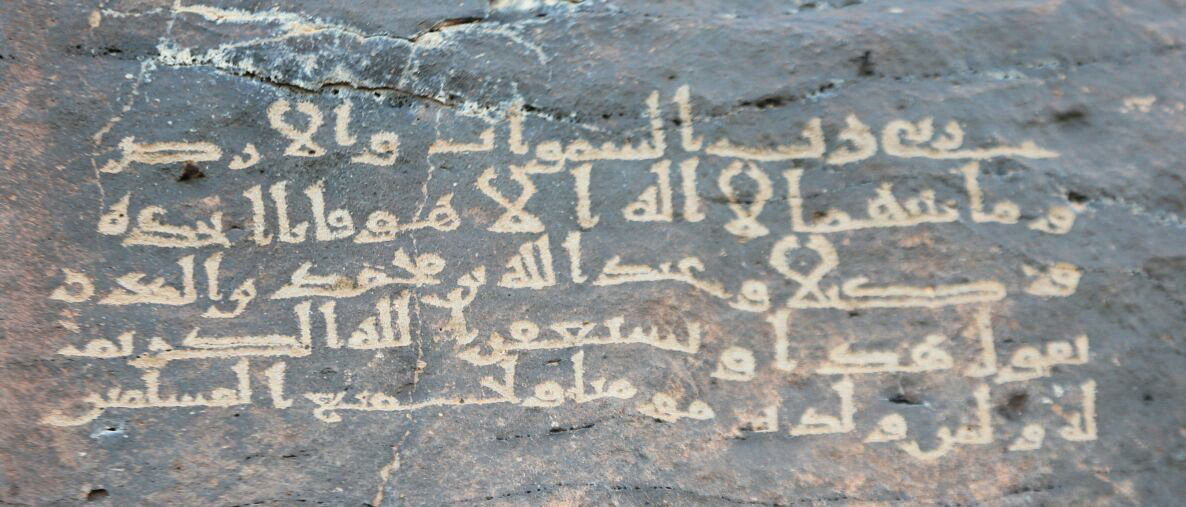

“Madani is characterized by the integrity and flexibility of its letters. This a distinctive feature,” says calligrapher Abdulaziz Al-Rashidi.

Noted for its roundness and rightward slope and shape of the final ya, which turns backward to underline the preceding letter — a common Hijazi characteristic — Madani is a foundational font bearing a visual through line from which later styles sprung and are connected. Its specific functions dictated its characteristic compactness or elongated strokes, with dashes above the letters to differentiate consonants and a lack of dots or diacritical marks to indicate vowel sounds.

In the Qur’an, it was presented in singular columns on vertical pages of animal skin parchment, and the lack of consonant points suggest that at that time the Qur’an was memorized rather than read. In the context of royal correspondence, Madani employed technical complexity to reduce the risk of forgery, which enhanced its bold, stately aesthetic.

The font employed employed technical complexity to reduce the risk of forgery, which enhanced its bold, stately aesthetic. (SPA)

But Madani is no reliquary tradition. “It is still relevant because it is an important visual reference of the classical origins of calligraphy,” explains Al- Rashidi.

Following King Abdul Aziz’s interest in the preservation of Arabic calligraphy, documents and manuscripts at the King Salman Center for Restoration and Conservation of Historical Materials at the King Abdul Aziz Historical Center, Prince Faisal bin Salman, governor of Madina, has worked to protect the Madani script by showcasing it in exhibitions.

In 2018, the King Fahd Complex for the Printing of the Holy Qur’an launched an initiative to digitalize the ancient font, while libraries including the Egyptian National Library, Paris National Library, the Leiden University Library, the University Library of Birmingham, and the Berlin Library hold Madani Qur’ans in their collections.

“The art of calligraphy is our identity and heritage,” says Al-Ali. “By preserving calligraphy, we are in fact preserving our identity as Arabs.”