CAIRO: New release “Electrosteen,” merges “Palestinian folk music with a modern electronic sound,” according to the press release from Mostakell Records, the Cairo-based independent label distributing the album.

A play-on the words ‘Electronic’ and ‘Falasteen’ (Palestine), the record brings together some of the country’s finest underground electronic music producers and DJs in “a cooperative take on Palestinian folk, roots and traditional song, mined from the archives of the Popular Art Center of Ramallah to give birth to an urban contemporary celebration of Palestinian heritage.”

A pre-launch concert for the album was held at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris last year. (AFP)

The album’s stellar line-up comprises SAMA’, Julmud, Al Nather, Muqata’a, Sarouna M., Nasser Halahlih, Bruno Cruz, and Walaa Sbait (of 47 Soul), in addition to guest appearances by Basel Naouri, Mehdi Haddab (Speed Caravan), and Shabjdeed. A pre-launch concert for the album was held at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris last year.

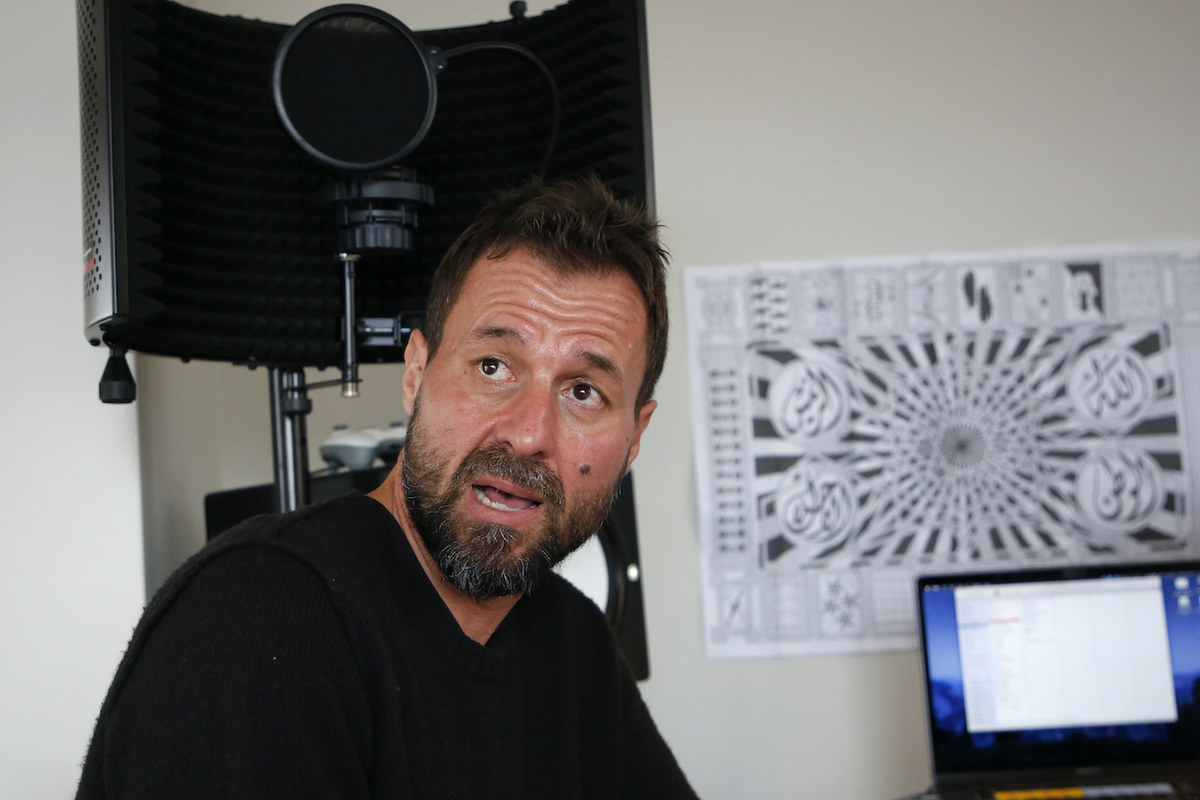

“The objective behind the album was to take our Palestinian turath (heritage) to electronic music festivals,” said album producer Rashid Abdelhamid, founder of Made in Palestine Project, an arts initiative “developing the appreciation of contemporary visual art and culture with a particular focus on Palestine,” according to its Facebook page.

Rashid Abdelhamid is the founder of Made in Palestine Project. (AFP)

Work on “Electrosteen” began in 2017 with a two-week residency in Ramallah, Palestine. Selected musicians were given access to an audio library owned by the Popular Art Center of Ramallah, and “collected from existing archives or recorded from professional and amateur urban, rural and Bedouin musicians,” according to the album description.

“Recordings go back 20 or 30 years. They were spontaneous and were made in Palestinian villages,” Abdelhamid told Arab News. “The artists were asked to work together to produce two original tracks each.”

A pre-launch concert for the album was held at the Institut du Monde Arabe in Paris last year. (AFP)

Those tracks, Abdelhamid said, are not simple “remixes” of folkloric samples. Rather, they are original productions that sampled those recordings.

“It was completely up to the musicians which recordings they used or how they incorporated them into their music. They used samples and sounds to create their own tracks, in much the same manner as adding Palestinian spices to one’s own creations,” Abdelhamid explained.

“The flavor of Palestinian turath remains very much present,” he added.

A play-on the words ‘Electronic’ and ‘Falasteen’ (Palestine), the record brings together some of the country’s finest underground electronic music producers. (Supplied)

Each night, the group held listening sessions and shared feedback. “It was a very democratic process,” said Abdelhamid, adding that even the album title was chosen collaboratively.

“Electrosteen” introduces an “alternative vision of Palestine” and shines “a spotlight on Palestine's cultural vitality and relevance in the contemporary world.”

In choosing electronic music, with its “universality and its political value,” the album “might very well play an important part in the struggle for a free and respected Palestine.”

“Electrosteen” should also make listeners rethink the Palestinian victimhood narrative, the press release suggests, and, with it, long-standing stereotypes that depicts Palestine and Palestinians solely “through the camera lens of war, occupation, in-fighting, and humanitarian strife.”

“I’m sick of the current image of the Palestinian-as-victim,” Abdelhamid adds.

In choosing electronic music, with its “universality and its political value,” the album “might very well play an important part in the struggle for a free and respected Palestine.” (Supplied)

It is not the politics that bothers Abdelhamid per se, because, “as Palestinians, waking up every day is, in and of itself, a political act. Everything we do in life is essentially political.” Rather, it is the abuse and appropriation of the Palestinian cause by art and artists that truly frustrates him. With “Electrosteen,” he said, “My main aim was to encourage the preservation and celebration of our Palestinian identity when performing electronic music in the West, and to introduce ourselves as musicians who have something to offer, instead of just ‘victims.’”

And for the producer, at least, the record meets those aims. “I’m very happy with the end result. And I think ‘Electrosteen II’ might follow soon,” he said. Although given his perpetual involvement in multiple new projects, it might not be easy for him to find the time.

“Whether it’s the production of films, music, or other art forms, in my own way I am constantly trying to shed light on anything beautiful in and about Palestine.”