CHICAGO: Every 10 years, the US census not only counts how many people live in America but also identifies their interests and national origins. It determines how more than $600 million in federal funding is dispersed to communities to address their concerns.

Additionally, census data is mandated to ensure equal representation and treatment in government.

Anna Mustafa, who emigrated to the US in 1962 to join her late brother and father who had already settled in Chicago, believes the importance of the 24th US census, known as Census 2020, cannot be overstated.

“Arab Americans need to be and have to be counted in the census,” she told Arab News.

“The census is very important because it determines the allocation of dollars, the political influence, and the representation that we and all Americans are entitled to in the US.

“The more Arab numbers there are, the more federal funding and the more political power we deserve. It’s like that for every other ethnic and racial group.”

FAST FACTS

• Lebanese Americans constitute a greater part of the total number of Arab Americans living in most states.

• Egyptian Americans are the largest Arab group in Georgia, New Jersey and Tennessee.

• Illinois has the greatest concentration of Palestinians.

• There are almost as many Iraqis living in Michigan as there are living in California.

Source: Arab American Institute Foundation

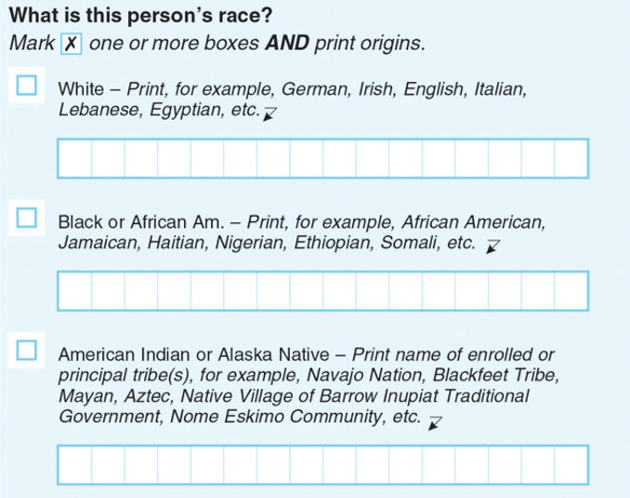

The census asks about many different ethnic and racial groups, including Whites, African Americans, Hispanics, Mexicans, Latinos, Asians, American Indians and Alaska Natives, Native Hawaiians, Pacific Islanders and the category of “Other.” But it has never included a category for Arabs.

Mustafa believes Arabs need to be acknowledged. Since her arrival in the US, the Arab population in Chicago and throughout the country has continued to increase. She and her family were inspired by President John F. Kennedy, who had defined himself as a champion of immigrants in his 1958 book “A Nation of Immigrants.”

Mustafa and others watched as the Palestinian and Jordanian communities steadily grew after the 1967 and 1973 Arab-Israeli wars as people fled political persecution in the 1980s and conflict in the 1990s.

Moved by Kennedy’s vision of an immigrant nation, Mustafa became involved in helping to accurately identify the Arab population. She was recruited by the country’s Census Bureau in the 1980s to encourage members of the Arab American community to complete census forms and become involved.

Mustafa quickly rose to leadership. She was appointed by Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley in September 1990 as the first and only Arab American trustee on the Chicago Board of Education, the third-largest school district in the US.

Samer Khalaf, American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee president, calls for census inclusion. (Supplied photo)

The board oversees education for more than 400,000 school students in 600 schools. Almost 10 percent of the students were Arab American, a result of the growth spurt in legal Arab immigration to the country.

The year 1990 was critical both for the US census and ethnic and racial minorities such as Arab Americans. The census that year showed that the Hispanic community’s growth was faster than that of Arab Americans, but the population was divided geographically into two large populations: Puerto Rican and Mexican Americans on Chicago’s North Side and a large concentration of Mexican Americans on the South Side.

Although the two areas were more than two miles apart, the government connected them in 1991 by “an umbilical cord,” creating one of the most unusually shaped Congressional districts ever drawn and Chicago’s first-ever Hispanic-majority district.

The district had been represented by white men since its founding in 1843. But on Jan. 3, 1992, Luis Gutierrez, a former cab driver and Chicago alderman, was sworn in as Chicago’s first Latino American Congress member.

“That showed me how powerful and meaningful the census really was,” Mustafa said. “By getting an accurate count of Hispanics in the census, the government was compelled to create a district for the Hispanic community. I felt if our Arab community was counted accurately, we could achieve the same political strength and success.”

Mustafa was recruited again by the Census Bureau in 2000 to help encourage Arab Americans to complete their census forms.

I wanted us to be identified as Arab, but others wanted us to be identified by individual national groups.

Anna Mustafa

Arabs could write in their ethnicity in the “Other” category, and there was a new drive to have the word “Arab” included among the dozens of other ethnic and racial groups already identified on the census forms.

Samer Khalaf, national president of the American Arab Anti-Discrimination Committee (ADC), said that Arab Americans have been pushing to be included in the census for more thanthree decades.

In recent years, there was a push to create the “MENA” category representing Middle East and North Africa.

“We believe that it is crucial for our community to be counted fairly and accurately,” Khalaf said. “They only way to do that with any certainty is to have a category for our community. The census’ own studies showed that when the MENA category was included, the numbers were more accurate.”

The push to create the MENA category began following the 2010 census during the administration of President Barack Obama, but it never received the support it needed.

In January 2018, the proposal was formally rejected by newly elected President Donald Trump. Despite the rejection, Khalaf said, the drive to create a category for “MENA” or “Arab” is far from dead. “We have been fighting for the category for about 30 years and we will continue fighting for it until it is added,” said Khalaf, who has been at the forefront of fighting for census inclusion for Arab Americans.

“Of course, my preference would be for an ‘Arab’ category. I believe it more accurately describes our community. MENA is purely a geographical designation with multiple definitions. The decision to agree to a MENA category was a compromise that the Arab American organizations made to facility the inclusion of the category.”

Race questions on 2020 Census

Mustafa also prefers “Arab,” although she said that it might be easier to get MENA passed as a category. The real problem is that many other Arab American organizations have focused on political power and funding, which has fueled divisions within the community, she added.

Today, the Arab American community is more divided, with fractures based on individual national identities and even on religion, she said.

“What’s holding us back is our community divisions, as well as people in the US government who don’t want us to be recognized or to have power.

“In 2000, I felt there was support to have a category for Arab Americans. But what happened was that in less than one year that support for the census disappeared.

“It seemed we started to make our own trouble. Our community started to divide itself and we became weak. I wanted us to be identified as Arab, but others wanted us to be identified by individual national groups such as Palestinians, Lebanese, Jordanians, Syrians, Iraqis, Egyptians, etc,” she said.

In the “White” category, the 2020 census form suggests that users identify their “race” and offers examples such as “German, Irish, English, Italian, Lebanese, Egyptian, etc.”

Today, no one really knows how many Arabs live in the US. The census has some data based on Arab Americans who check the “Other” box but add the word “Arab.” Based on that incomplete practice and extrapolating on a 2013 analysis of data collected during the 2010 census, the Census Bureau believes there are only 1.9 million Arabs in the country.

But groups such as ADC and the Arab American Institute (AAI) argue that the actual number is much bigger — almost 3.7 million roughly. Still others insist the figure is greater than 4.5 million, with high concentrations in Chicago’s suburbs.

According to the Arab American Institute’s data on demographics, there are more than 324,000 Arabs in California, 223,000 in Michigan, 152,000 in New York, 124,000 in Texas, 112,000 in Florida, 111,000 in Illinois and 108,000 in New Jersey, with smaller populations in Ohio, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania.

Last week, a New York federal judge barred President Trump from placing a question on the 2020 census that would ask Americans if they are citizens, and the public debate over the census has been muted. Ironically the “citizenship” question was always on the census forms until 2010, when it was quietly removed without much fanfare.

While Americans continue to focus on issues of legal and illegal immigration, Arab Americans are left wondering when they will be counted. Or, as Mustafa puts it: “When will Arab Americans get their fair share in funding and representation?”