DUBAI: For millennia, birds have made their journeys through global flyways, and the Middle East is a significant stopover on their flight path.

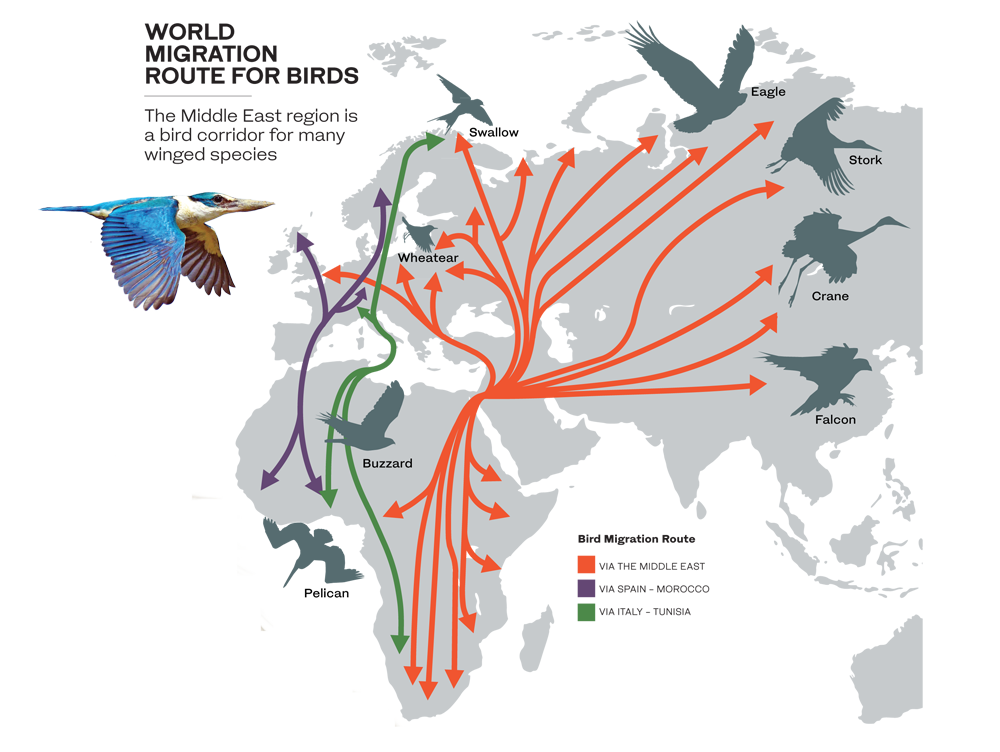

Twice a year, billions of birds migrate vast distances across the globe, typically following a predominantly north-south axis linking breeding grounds with non-breeding sites. The Middle Eastern region, located at the juncture of three continents, Europe, Asia and Africa, is a major bottleneck and bird corridor for many winged species, including the willow warbler, the barn swallow, the Amur falcon and Steppe eagles.

“Birds breed in summer in the north and then winter in the south — that is fundamentally what migration is around,” said Nick Williams, head of the coordinating unit at the Convention on Migratory Species’ African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbird Agreement.

Speaking to Arab News as World Migratory Bird Day is marked on May 11, the UAE-based expert said: “There are also other migratory trends; species that just move laterally for reasons such as food resources. Here in the region, we are very well placed because we are right in the middle of Africa and Eurasia, and there are several types of species that arrive in the summer and breed here.”

These include the Sooty falcon, which migrates from Madagascar, a known wintering area for the species, to the Arabian Peninsula, the journey migratory birds take between their breeding and wintering places.

The peregrine falcon, which breeds in the Arctic tundra, also travels through the Middle East corridor, as does the saker falcon, which breeds in the Republic of Kazakhstan but spends its winter season in the region. Several breeds of eagles and the Amur falcon breed in China and winter in North Africa, passing through the Middle East en route.

Common bird sightings, Williams said, include warblers, waders, finches and swallows. But more than 800 species of birds are known to breed in the region. “Then there are other groups of birds which visit us briefly — even for a matter of days or even hours — stopping off for a rest,” he said.

Such birds use food resources such as berries and insects that disappear in more Arctic countries during winter. Different types of birds take routes of widely varying lengths. Some round-trip migrations can be as long as 70,000 kilometers, equivalent to almost two round-the-world trips.

Williams said that many of the world’s migratory birds are in decline, and the region’s geographical distinctness means it has a key part to play in conservation efforts.

“For migratory species, no matter how much resources and how much individual efforts a single country puts into that exercise, all that good work can be undone as soon as migratory birds leave the border of that country if the next country lacks the same control measures,” he said. “If any of these countries don’t take action it cuts the chain.”

“Illegal shooting in one or two countries in the region such as Lebanon is rife and completely mindless and is causing massive problems,” he said. “Lebanon is struggling to control the hunting phenomenon. They have lots of challenges at the present — such as from migrants from Syria — and their resources are stretched, and therefore conservation tends to be bottom of the list.”

Hunting practices can include the illegal trapping of falcons, with poachers then selling them on.

When it comes to conservation, countries such as Saudi Arabia, Williams said, are doing “good work on this front.”

The Kingdom is one of 11 countries that are signatories of the Migratory Soaring Birds (MSB) project, an initiative which aims to protect the Middle East’s flyway from the illegal killing of migratory birds.

“What we are trying to do is to promote coordinated flyways, swim-ways and migration routes,” said Williams, adding that birds of prey face a variety of human-induced threats such as habitat loss and degradation, illegal shooting and poisoning, collisions with aerial structures and, often, electrocution by power lines.

Recently the UAE’s Mohamed Bin Zayed Raptor Conservation Fund signed an agreement with Mongolia’s Ministry of Environment and Tourism to tackle the alarming rise in electrocution-related deaths caused by power distribution infrastructure in the east Asian country.

Birds, Williams said, are important because they keep systems in balance: They pollinate plants, disperse seeds, scavenge carcasses and recycle nutrients.

There are other conservation initiatives in the Middle East, such as BirdLife International’s Flyways program, the Sustainable Hunting Project and Wings Over Wetlands Project, that Williams said are vital.

“Although migratory species are just one sector of biodiversity, it is an important one, and everyone — even from the grassroots level — can do their bit to help. Human-induced threats are the biggest threat to migratory birds,” he said.