Popeye, the scruffy sailor who remains one of the most loveable characters of all time, has been a popular fixture in Middle Eastern pop culture since the early 1980s. In addition to mountains of merchandise, particularly stuffed toys, being available in local shops, the cartoons were broadcast on Saudi Channel 2 (in their original English) and on Spacetoon (with Arabic dubbing).

“I remember the first time I watched Popeye,” Zainab Basrawi, a 36-year-old insurance lawyer and self-professed Popeye enthusiast, told Arab News. “I learned to love spinach just from watching him save Olive every time. I believed him. I think he was a great influence on children to subtly ease them into eating their greens.”

Just one week after Tintin first appeared in “Le Petit Vingtieme,” Popeye made his debut on Jan. 17, 1929 as a side character in the daily King Features comic strip “Thimble Theatre.”

Created by the American cartoonist Elzie Crisler Segar, the one-eyed sailor with bulging forearms quickly grew in popularity, becoming the star of his own strip, an animated TV cartoon and a 1980 movie starring

Robin Williams. The theme song from the cartoon, “I’m Popeye the Sailorman,” is one of the most recognized pieces of music in pop culture history.

Compared to boyish, clean-cut, good- natured Tintin, Popeye is his polar opposite.

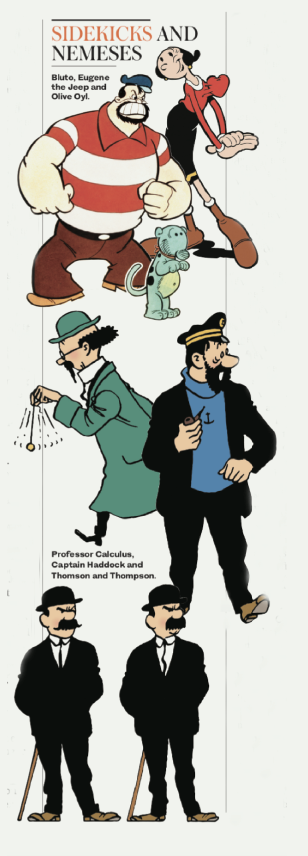

The sailor is rough, gruff and extremely tough, famous for the super-strength he gets from eating canned spinach, and his never-ending love triangle with his girlfriend Olive Oyl and rival Bluto.

Like Tintin, as a relic from another era, Popeye has also been criticized for racial stereotypes. In “Popeye the Sailor Meets Ali Baba and His Forty Thieves,” he is shown beating up poorly made caricatures of Arab men. In “You’re a Sap, Mr. Jap,” the Japanese characters in the cartoon get the same treatment.

However, literary critic Sophie Cline said the comic strip is reflective of the time it was created in, almost a century ago. “I think it’s important not to ignore these pieces of our history, or hide them away, but rather to own up to our mistakes and learn from them,” she told Arab News.

She alluded to the new disclaimer that now precedes old Looney Tunes cartoons, informing viewers that their outdated “racial prejudices” no longer reflect Warner Bros. values but are “products of their time.”

She alluded to the new disclaimer that now precedes old Looney Tunes cartoons, informing viewers that their outdated “racial prejudices” no longer reflect Warner Bros. values but are “products of their time.”

“Popeye cartoons reflect the common view of the era,” she said. “A disclaimer should be enough.”

Tintin, one of the world’s most famous fictional journalists, traveled the world seeking stories and adventure, so he naturally spent a good amount of time in the Middle East.

Created by Belgian cartoonist Georges Remi, better known by his pseudonym Herge (say his initials in reverse out loud in a French accent), Tintin travels the region in four of his books: “Cigars of the Pharaoh,” “The Crab with the Golden Claws,” “Land of Black Gold” and “The Red Sea Sharks.”

Tintin gained more of a foothold in the region when Egyptian publisher Dar Al-Maarif began printing the comics in Arabic in 1971. Renaming him “Tantan,” Dar Al-Maarif continued to publish the comics weekly

until 1980.

“Tintin has been one of my idols for as long as I can remember,” said Haytham Faisal, a journalist from Cairo. “I literally became a journalist because I wanted to be him. My dad used to take me to buy the comics from the local bookstore. I remember them being so expensive, so they were a rare treat. I’d always think twice before buying them, but I couldn’t always wait for the next comic to see what new story they have next. I still have some of them, they were that precious to me.”

Before appearing in book format, Tintin and his constant companion, the dog Snowy, were first introduced to audiences in “Le Petit Vingtieme,” or “The Little Twentieth,” a supplement to the Belgian newspaper “Le Vingtieme Siecle” (The Twentieth Century) on Jan. 4, 1929. Herge, however, maintained that Tintin was actually “born” on Jan. 10, when “Tintin in the Land of the Soviets” began its serialization in the paper.

Despite the fact that he never seems to hand in any stories, the loveable and quirky Tintin is portrayed as talented at his profession, so much so that he is shown to be in high demand, with many press agencies offering him bribes for his dispatches.

Over the years, Tintin’s face has been used to advertise quintessentially French items such as Citroen cars and La Vache Qui Rit cheese. Enthusiasts of Tintin lore, known as Tintinolo- gists, have written entire books devoted to him.

Since 1929, more than 250 million copies of the Tintin comic books have been sold. His adventures have been translated in more than 110 languages, and the books are sold in almost every country in the world.

Tintin continues to grow in popularity, even 90 years on. He was the star of a full-length feature film, directed by Steven Spielberg, in 2011 and of an animated television series. The latter was broadcast on Saudi Channel 2 between 1991 and 1992 and a dubbed version has been on MBC 3 since 2003.

However, the history of Tintin has not been without its hiccups. Over the years, critics have argued that, like many of the comics of the era, it should undergo censorship or even outright banning from bookstores and libraries. One of the more troublesome ones is his second adventure, “Tintin in the Congo.”

The natives Tintin visits are crude stereo- types of African people, who are portrayed as ignorant and uneducated, and the references to slavery, such as when the natives refer to Tintin as “master,” make the comics hard to stomach.

Similarly, “Land of Black Gold,” which takes place in a fictional Red Sea state named Khemed, is also banned in several Middle Eastern countries today for its stereotypical portrayal of Arabs.

While some argue the comics are simply byproducts of their era, they are nonetheless somewhat difficult to revisit in the modern era. Attempts have been made to soften some of the references, with edits being made to “Tintin in the Congo” in 1975, but is that enough?

Not according to the London-based human rights lawyer David Enright, who wrote in the Guardian newspaper that “Tintin in the Congo” shouldn’t be sold to children. “Books are precious, but so are the minds of young children. It is vital that our children learn and explore the grotesque history of slavery, racism and anti-Semitism, but in the proper context of the school curriculum.”