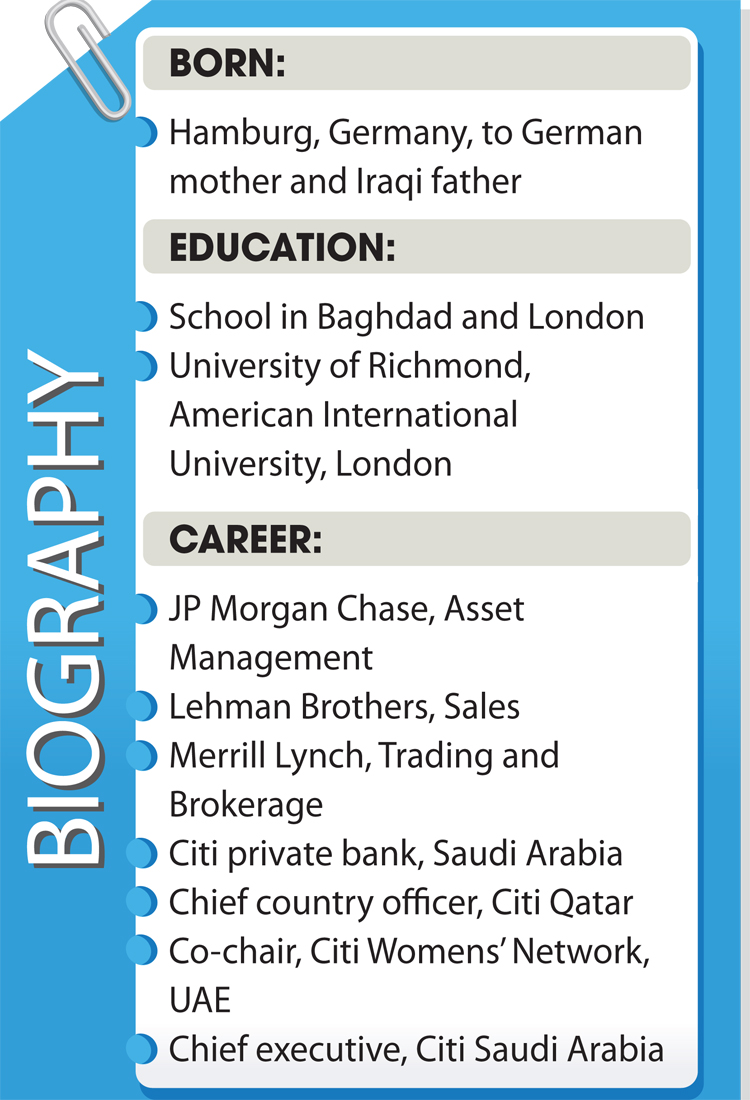

DUBAI: Business journalists had a problem when Carmen Haddad was appointed chief executive of Citibank in Saudi Arabia earlier this year: What was the top story?

Was it the fact that a woman had been appointed to such a high-profile job in the Kingdom? Or was it the fact that there was a Citi operation in Saudi Arabia for her to take charge of?

Her appointment came at a time when other women were also being promoted to top financial jobs in Saudi Arabia, in what Haddad regards as the “vanguard” of the movement for female empowerment.

Citi had been formally out of the Kingdom for 13 years, since it sold its stake in Samba Financial Group and lost its banking license, in a move that senior executives said soon after was “a mistake.” The US banking giant later tried unsuccessfully on two occasions to get Capital Markets Authority (CMA) recognition.

In fact, Haddad’s appointment was a clear signal that Citi was back, and that the bank also recognized that Saudi Arabia was changing with the economic transformation process underway as the Kingdom seeks to reduce its dependency on oil revenues.

“Our strategy in Saudi Arabia is a long thought-out process, evolving over the past 10 years. We’ve never really left a major country before, and there were unusual circumstances surrounding our exit from Saudi Arabia back then. The opportunities presented by Vision 2030 made our return possible,” she said last week in an exclusive interview in the bank’s Dubai office.

Citi made its presence felt at the Future Investment Initiative conference in Riyadh in October, when heavy-hitting executives traveled from the bank’s headquarters in New York to take part in the event nicknamed “Davos in the desert.”

James Forese, president of the banking group and head of institutional business, and Tyler Dickson, head of global capital markets, attended the event in a signal that Citi was back in the KSA, big time.

Haddad said this set the seal on a process that had been some time in the making. “Of course, in one sense we never left Saudi Arabia, because we maintained our good relations with the Kingdom and established a track record via our offshore operations, for example via our involvement in the $10 billion syndicated loan in May 2016, and then the big $17.5 billion bond issue in October that year, where we were one of the global coordinators,” she said.

“That left us well-placed to get the CMA license for investment banking activities last April. It gives us the ability to undertake the full range of activities — mergers and acquisitions, initial public offerings (IPOs), privatizations, capital markets, debt and equity transactions, treasury, and next year we will begin custody operations,” she added.

The bank is not — so far — involved in the planned IPO of Saudi Aramco, the national oil company that will form the centerpiece of the biggest privatization program in history. If the Aramco sale goes ahead at the suggested $100 billion valuation, it will be the spark for a sell-off of state assets that could bring in as much as $300 billion in total over the next few years.

That is bigger than the pioneering privatization program of Britain in the 1980s, and the great sell-off of Soviet state assets after the end of communism in the 1990s. Those are two contrasting models for government asset sales, which Citi must have taken into account when it developed its own global privatization strategy for Greece, Pakistan and elsewhere.

Citi is hoping that track record will be put to good use by the Saudi privatizers, and avoid the issues of past sales, as seen in the Soviet experience.

Haddad said: “We have done a lot of strategic advisory work with the National Center for Privatization (NCP). We have a long track record in privatization work around the world, and we are giving the benefit of our experience in advising on what is regarded as best practice.

“There are of course many different models of privatization to follow. Now, they (Saudi policymakers) are thinking long-term in a strategic and commercial sense, and I think they will avoid the mistakes of past privatizations in history,” she added.

There has been some speculation that the Saudi privatization program has already fallen behind schedule, and that the whole program will not be underway until 2019. Some experts have pointed to the lack of a legal and regulatory framework in which to conduct such a massive sell-off.

“I believe the infrastructure for privatization is being made ready. There certainly seems to be a lot of planning and preparation. The execution stage always presents a challenge, and you need to find the talent to see it through as well,” Haddad said.

She understands the importance of talent. The ties with the privatization policymakers will be strengthened by the recent appointment of Majed Al-Hassoun as head of Citi’s investment banking operation in the Kingdom. Formerly with the investment banking arm of Banque Saudi Fransi, Al-Hassoun spent some time on secondment with the NCP.

That was the second crucial appointment by Citi from the Saudi homegrown financial community, after it hired Fathi Al-Tarouti from Societe Generale, as head of markets.

The appointments slot in a vital piece of the Saudi jigsaw. Haddad said: “This is in line with our aim to hire top Saudi talent to oversee Citi’s operation on the ground.” The aim is to be fully operational by the first quarter of next year, with up to 20 employees there.

There are no plans, however, to go back into retail banking in the Kingdom, which would require a separate license from the Saudi Arabian Monetary Authority in a market regarded by many analysts as already over-banked. “We believe that the local market is highly mature and we aim to complement the banking infrastructure of the Kingdom, not compete with it,” she said.

But it is clear that Citi sees plenty of opportunities in investment and other forms of banking, without having to fight for retail business. She talked enthusiastically about the big projects being planned in the Kingdom, and the potential for Citi’s involvement in them.

“Saudi Arabia is going through a transformational phase at societal and economic levels which requires trusted and time-tested advice. We will consider all our options and deploy all relevant resources in support of Vision 2030.

“We are excited about breakthrough projects such as Neom, which Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced recently, and we can certainly lend our global expertise in the area of public-private projects (PPP) to such mega plans as part of our offering,” she said.

In particular, Haddad sees bright times ahead for the Public Investment Fund (PIF), the financial institution being groomed to become a global giant. “I think PIF has such an incredible opportunity, and the very exciting prospect of being the biggest SWF in the world,” she said.

There is one issue Citi faces in its new-found status in the Kingdom. Some commentators have speculated that the presence of Prince Alwaleed bin Talal as a big, long-term shareholder in Citi, and the banks’ decades long relationship with him, might hamper its ability to get government business in the wake of the anti-corruption campaign underway in the Kingdom.

Haddad did not want to talk about this, and instead relayed the comments of the Citigroup global chief executive Michael Corbat.

In a recent interview, Corbat said: “I would say in our interaction, and we’ve known Prince Alwaleed for 25 years, is he’s been a very consistent, loyal supporter of our company. He’s been with us in good times and bad times and hopefully back to good times … And so we look at some of the progressive things that are happening there, and we’re encouraged by it.”

In the same interview, the group chief executive made a point of highlighting the fact that Citi had a woman in charge of the Saudi operation, and Haddad seemed justifiably proud of her pioneering role in the new Saudi financial hierarchy.

“I see myself and other women — like Rania Nashar, chief executive of Samba Financial Group, and Sarah Al-Suhaimi, chair of Tadawul — as being in the vanguard. Change is certainly coming. It’s not just in the big policy statements, but in small things from logistics — driving a car — to transformational changes for women, where we can compete in the workforce for equal opportunities.

“The inclusive and diverse approach to the role of women is indeed exciting and will support the necessary efficiencies going forward. There is so much benefit to be gained from such greater freedom of movement and greater efficiency,” she added.

But at the end of the day, whatever the circumstances in the Kingdom, Citi decided a long time ago that it was an opportunity that was too good to be overlooked any longer.

“Saudi Arabia is an important strategic market and we have taken the view that we cannot be in the Middle East without being in its biggest economy. We will consider all our options and deploy all relevant resources to serve Saudi Arabia. We are committed and here to stay,” Haddad said.

An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the license lost by Citibank in 2004 was with the Capital Markets Authority (CMA). This was not the case: The license was with SAMA at the time. The reference has been amended in the above text.