WASHINGTON: Eager to show strength after a major provocation, President Donald Trump is forcefully denouncing a chemical attack he blames on Syrian President Bashar Assad but staying coy about how, if at all, the US may respond.

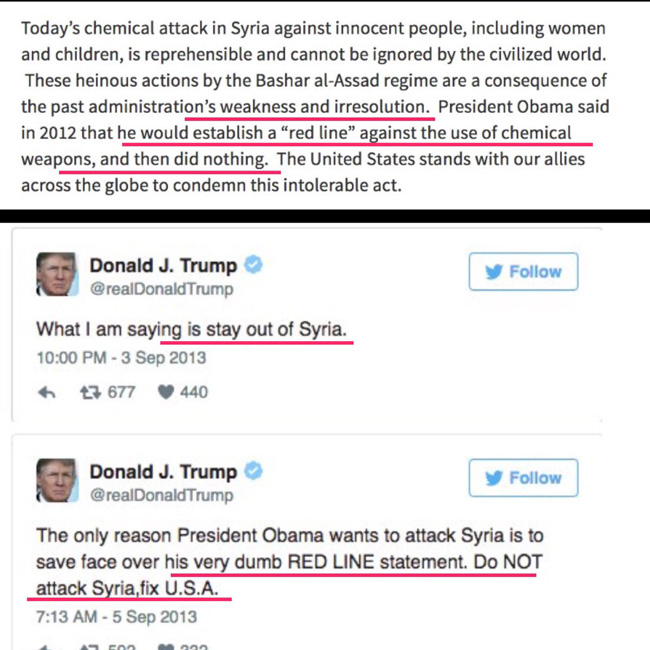

Trump split the blame Tuesday between Syria’s embattled leader and former President Barack Obama for the country’s worst chemical weapons attack in years. While calling the attack “reprehensible” and intolerable, Trump reserved some of his harshest critique for his predecessor, who he said “did nothing” after Assad in 2013 crossed Obama’s own “red line.”

“These heinous actions by the Bashar Assad regime are a consequence of the past administration’s weakness and irresolution,” Trump said.

Yet there were no indications Trump had a plan to prevent future atrocities that was any different from Obama’s. Asked how Trump might respond, White House press secretary Sean Spicer said he wasn’t yet ready to discuss it.

“We’ll talk about that soon,” Spicer added.

Obama, too, faced a dearth of good options in Syria, which he has often acknowledged as the biggest failure of his presidency. Years after Obama predicted that Assad’s days were numbered, the Syrian leader remains in power in a country ripped apart by civil war, and a new US president is struggling to establish a way forward.

Trump left it to his top diplomat, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson, to assign culpability to Russia and Iran, Assad’s most powerful allies. Tillerson noted both countries signed up as guarantors to a recent Syrian cease-fire and said they must pressure Assad not to conduct more such attacks.

“Russia and Iran also bear great moral responsibility for these deaths,” Tillerson said.

Relying on Russia

Yet it was a mainstay of Obama’s approach to Syria to try to persuade Moscow to stop supporting Assad and clear the way for a political transition. Instead, Russia launched a military operation in Syria that successfully propped up Assad’s regime, strengthening Russia’s influence in Syria and the broader Middle East in the process.

And Tillerson’s predecessor, John Kerry, negotiated painstakingly with his Russian counterpart to secure cease-fire deals that repeatedly fell apart.

“This is the administration in charge. They are now facing exactly the same terrible dilemmas that Obama faced and will quickly realize there are no easy ways to deal with the situation,” said Phil Gordon, Obama’s top Mideast adviser from 2013 to 2015. “In that sense, the Trump administration is simply recognizing the reality: We are not, and have not been, prepared to do what’s necessary to overthrow the regime.”

Four years ago, after warning Assad that a chemical attack would cross a red line and trigger US action, Obama failed to follow through. Rather than authorizing military action against Assad in response to a sarin gas attack that killed hundreds outside Damascus, Obama opted instead for a Russian-backed agreement to remove Syria’s chemical weapons stockpiles.

Contradicting himself

The chapter was seen internationally as a major blow to US credibility and, for Obama’s critics, a prime example of weak leadership. Syrian chemical weapons attacks continued after the deal.

Yet at the time, Trump was squarely in agreement with Obama’s ultimate decision. Among his tweets on the matter, he urged Obama in all caps, “DO NOT ATTACK SYRIA — IF YOU DO MANY VERY BAD THINGS WILL HAPPEN.”

Obama aides declined Tuesday to comment on Trump’s assignment of blame for the new chemical attack.

Yet the political tone of Trump’s statement took many US officials by surprise. They noted that US presidents have rarely attacked their predecessors so aggressively for events like chemical weapons attacks that Democrats and Republicans both abhor.

Several officials involved in internal administration discussions said Trump’s National Security Council had been preparing a different statement, until the president’s closest advisers took over the process. The officials weren’t authorized to speak publicly on the matter and demanded anonymity.

The Britain-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights said at least 72 people, including 11 children, died in the town of Khan Sheikhoun. Witnesses claimed Sukhoi jets operated by the Russian and Syrian governments were involved. Videos from the scene showed volunteer medics using firehoses to wash the chemicals from victims’ bodies and lifeless children being piled in heaps.

US officials said there were some indications nerve gas had been used, though they suggested it could also be another in a series of chlorine gas attacks by Assad’s military. Chlorine isn’t a banned chemical substance, though it cannot be used as a weapon of war.

There are competing forces pulling at the Trump administration as it faces one of its first major foreign crises. While Trump tries to show he’s dealing with extremist groups in Syria more aggressively than Obama, his administration has suggested it could align with Russia, Assad’s key military backer. And in recent days, top US officials like UN Ambassador Nikki Haley have suggested that Assad’s removal is no longer a US priority.

But America’s Arab and European allies oppose any accommodation with Assad. Tillerson, in Turkey last week, outraged some foreign partners when he said Assad’s future was up to the Syrian people. And the idea of even an indirect alliance with a Syrian government that is gassing its own people will be a hard sell with a US public appalled by the reams of footage of the six-year civil war’s horror.