Juhayman:

40 years on

On the anniversary of the 1979 attack on Makkah's Grand Mosque, Arab News tells the full story of an unthinkable event that shocked the Islamic world and cast a shadow over Saudi society for decades

The sacrilegious storming of the Grand Mosque in Makkah by armed fanatics in November 1979 sent a shockwave through the entire Islamic world.

For the citizens of Saudi Arabia, however, the greatest shock was yet to come.

The Middle East was already on a knife edge. In Iran, a liberal monarchy that had ruled for almost four decades had just been overthrown by a fundamentalist theocracy preaching a return to medieval religious values that many feared would pollute and destabilize the entire region.

And then, murder and mayhem erupted in the very heart of Islam, perpetrated by a reactionary sect determined to overthrow the Saudi government and convinced that one among their number was the Mahdi, the redeemer of Islam whose appearance, according to the hadith (Prophet's sayings), heralds the Day of Judgment.

Ahead lay two weeks of bitter, bloody fighting as Saudi forces fought to reclaim the Holy Haram in Makkah for the true faith, but that battle was merely the overture to a war for the very soul of Islam in the Kingdom.

Open, progressive and religiously tolerant, Saudi Arabia was about to travel back in time. Only now, as the Kingdom pushes forward into a new progressive era of transparency and modernization, can the full story of the siege of Makkah and the regressive shadow it would cast over the country for the next 40 years finally be told.

The most unholy outrage

A plan to attack Islam's holiest place

'Every inch of the Grand Mosque is steeped

in history and spiritual significance.'

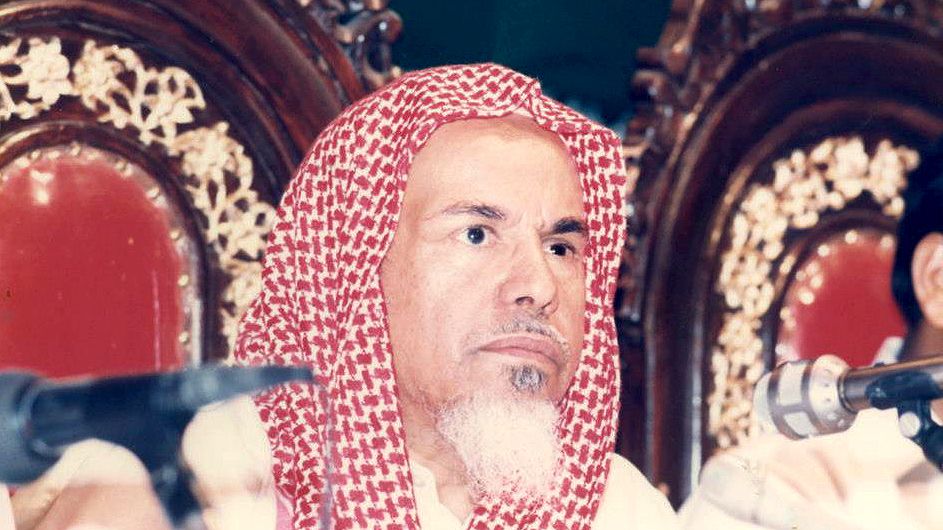

Prince Turki Al-Faisal explains the concept of the Mahdi and how the ideology was used by Juhayman Al-Otaibi’s group.

Prince Turki Al-Faisal explains the concept of the Mahdi and how the ideology was used by Juhayman Al-Otaibi’s group.

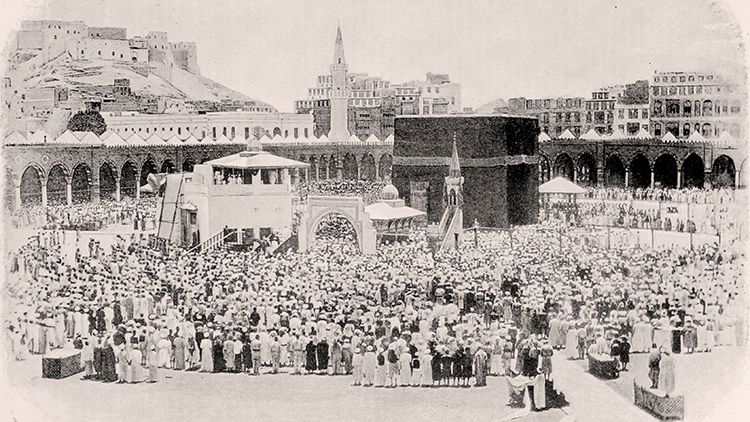

Throughout October 1979, close to a million Muslims from around the world had flooded into Makkah for Hajj, the pilgrimage to the spiritual heart of Islam that every physically and financially able believer is obliged to complete at least once in their lifetime.

For poor and wealthy alike — from the humblest Muslim who had saved for years to make the journey, to Sheikh Zayed, the founder and president of the UAE who had chosen this year to perform Hajj — the spiritually bonding experience of renewing their commitment to the faith in company with fellow believers at the Grand Mosque, the largest in the world and the birthplace of Islam, would be one they would never forget.

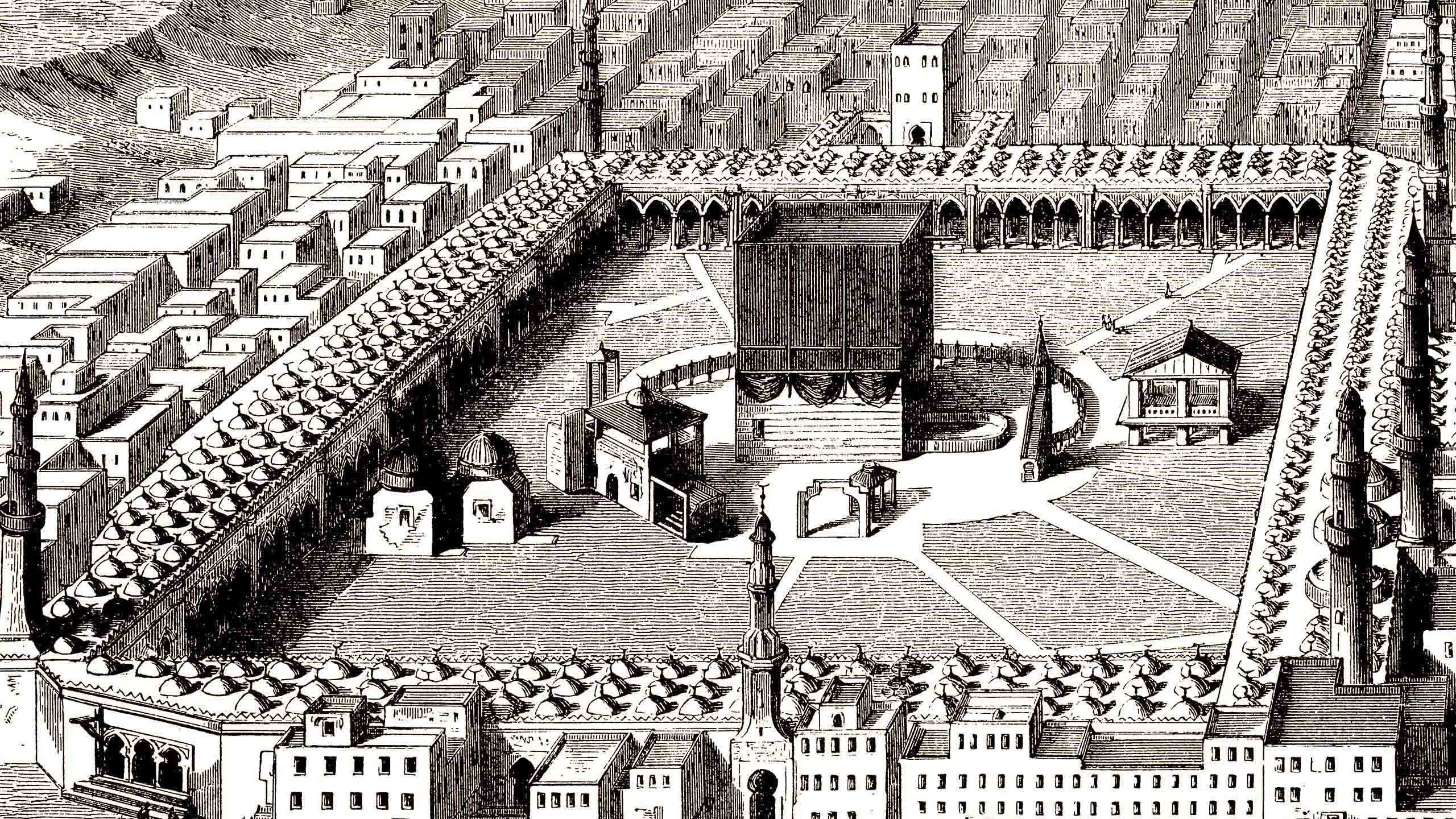

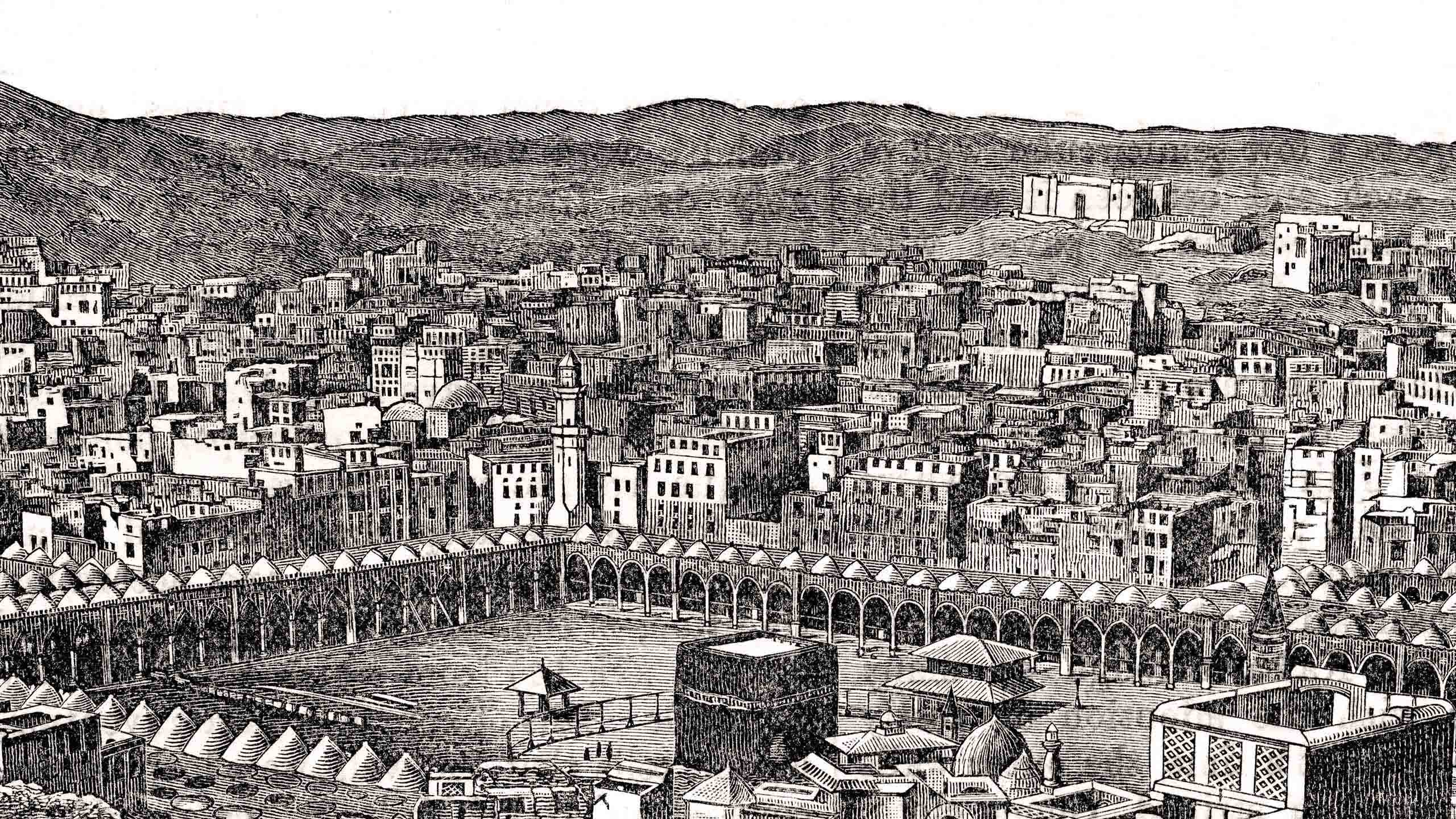

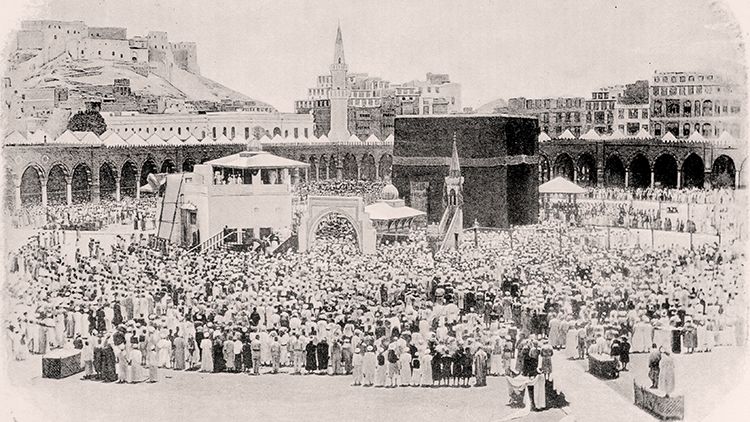

Every inch of the Grand Mosque is steeped in history and spiritual significance. In the vast courtyard at its heart stands the Kaaba, the cube-shaped structure which the Qur’an records was built by the Prophet Abraham and his son Ishmael as the first house of God.

Considered by Muslims to be the most sacred place on Earth, it is toward this shrine that believers around the world face five times a day throughout their lives as they conduct their prayers.

Crowds on a pilgrimage surround the Kaaba in July 1889. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

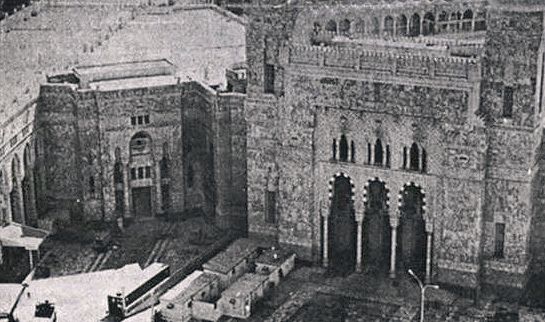

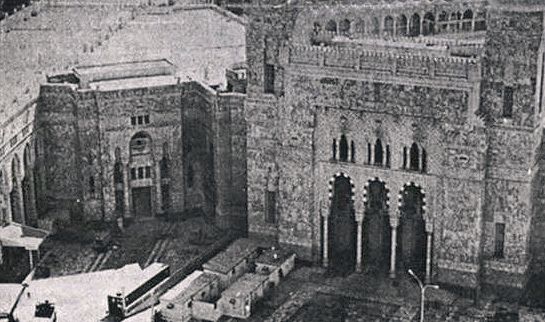

Pilgrims in the Safa-Marwa gallery in 1965. Keystone Features/Getty Images

Embedded in the eastern corner of the Kaaba is the Hajjar Al-Aswad, or Black Stone, a relic believed to date back to the time of Adam and Eve. During the Hajj Tawaf ritual, in which pilgrims circle the Kaaba seven times in an anti-clockwise direction, many seek to kiss, touch or at least point toward the stone, emulating the example set by the Prophet Muhammad.

Also in the courtyard is the Zamzam well, the site of the miraculous spring that materialized to quench the thirst of Abraham’s wife Hagar and their son Ishmael after he left them alone in the desert at God’s command. While the well was later covered over, mother and child’s desperate search for water is commemorated during Hajj by the Sa’ay ritual, in which pilgrims walk or run seven times between the twin hills of Safa and Marwa.

Today, these two hills are joined by a covered gallery connected to the Grand Mosque, a sprawling building that over the centuries has undergone many additions and improvements to accommodate the ever-increasing number of pilgrims performing Hajj, the spiritual journey to the Kaaba, and Umrah, which can be completed at any time of year.

Through the years, Saudi rulers have expanded the mosque to accommodate the number of worshippers. A large expansion, begun in the 1950s during the reign of King Saud, had been largely completed, but on the eve of the Islamic new year in 1979 some work remained to be done — and it was the temporary smokescreen of building work that the terrorists who seized the mosque on Nov. 20, 1979, were able to exploit.

As the citizens of Makkah and those pilgrims who had remained behind after Hajj saw out the final hours of Dhu Al-Hijjah, the 12th and final month of the Islamic calendar, and prepared to greet the year 1400 in prayer within the precincts of the Holy Mosque, a few inconspicuous pickup trucks slipped unchallenged into it through an entrance used by construction workers under the Fatah Gate, on the north side of the mosque.

The Fatah Gate, near where Juhayman's group drove pickup trucks through an entrance used by construction workers. Haramain Archives

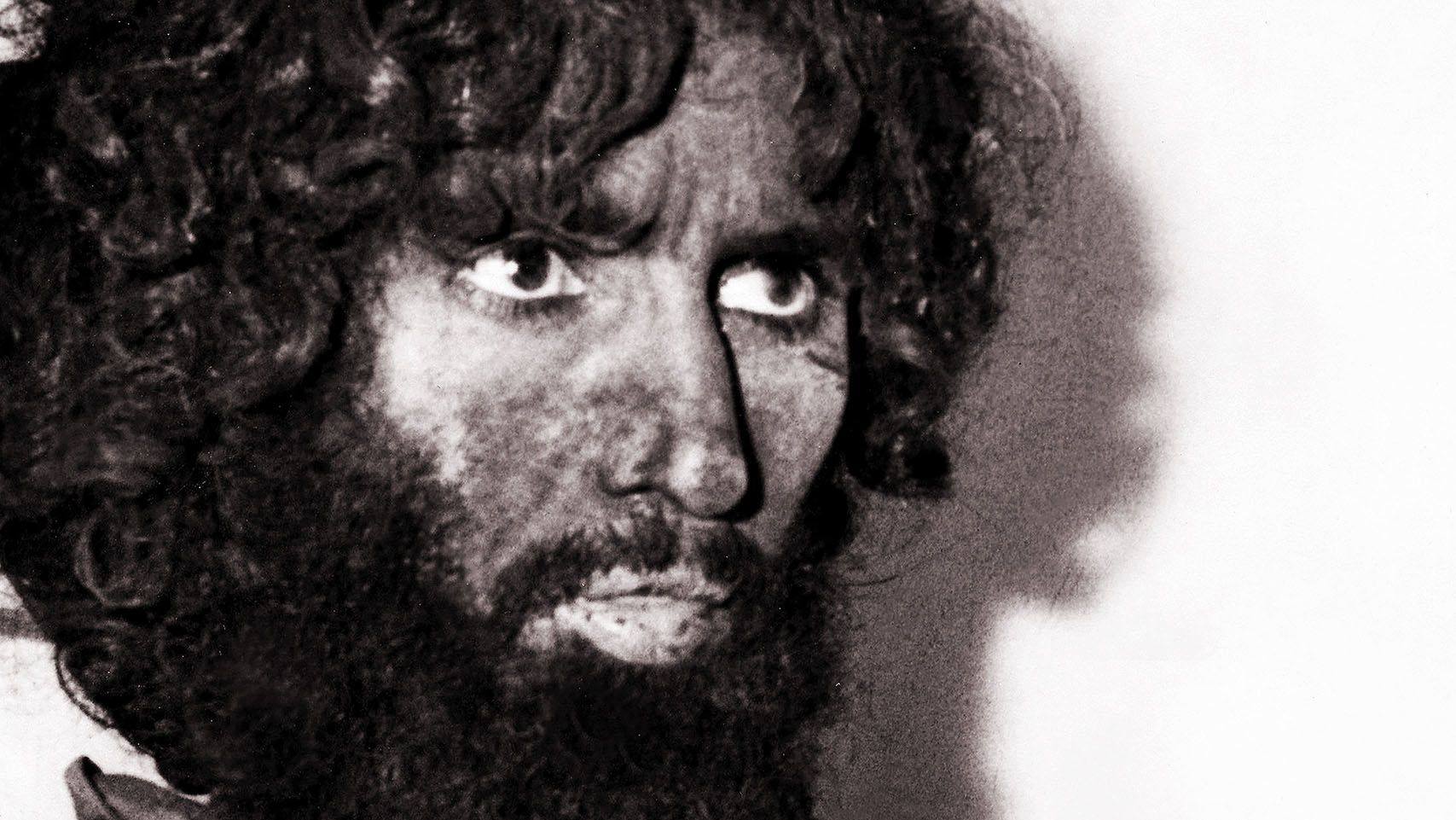

The trucks and the men who drove them were there at the bidding of Juhayman Al-Otaibi, a disaffected former corporal in the Saudi National Guard who had become seized by the belief that the rulers of Saudi Arabia, regarded by the entire Islamic world as keepers of the faith and the custodians of the holy mosques of Makkah and Madinah, were in fact responsible for turning Islam from the true path.

As an editorial in Arab News was to put it on Dec. 5, 1979, two weeks after the start of the most extraordinary episode in the modern history of the Grand Mosque, Juhayman and his followers “were a group of religious extremists who believed that the society around them was filled with infidels and that they must use force to change that situation.”

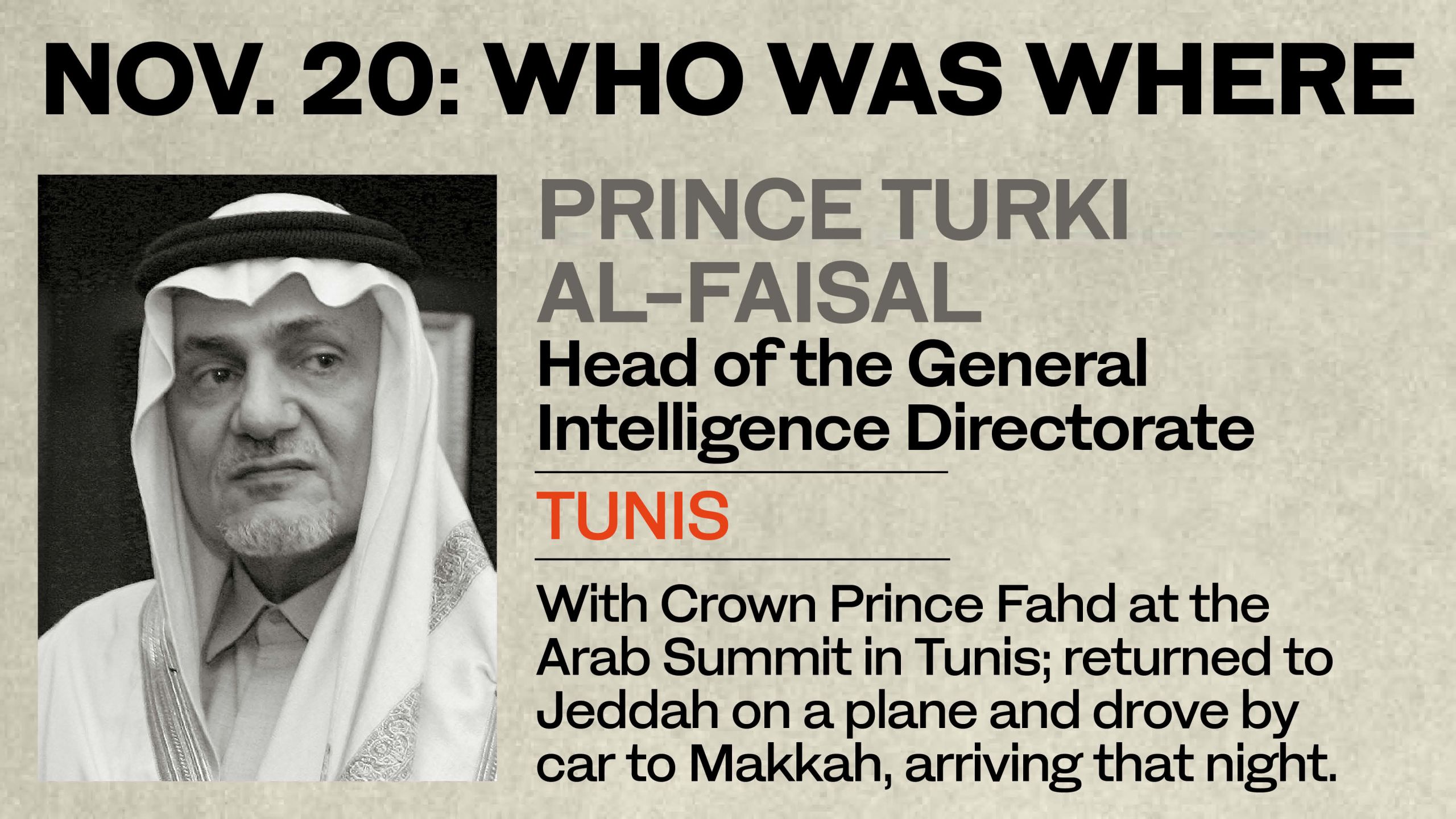

As a firebrand at the head of a small group of religious students based in a small village outside Madinah, Juhayman had been on the radar of the authorities for some time. According to Prince Turki Al-Faisal, who in 1979 was the head of Saudi Arabia’s General Intelligence Directorate, the group consisted of students from various religious seminaries who had put their faith in the eschatological figure of the Mahdi, the supposed redeemer of Islam.

“Their aim, according to their beliefs, was to liberate the Grand Mosque from the apostate rulers of the Kingdom and to liberate all Muslims by the coming of the so-called Mahdi,” Prince Turki said in an interview with Arab News.

“This whole concept of the Mahdi is a religious offshoot that is also present in other religions, such as Judaism and Christianity. It describes the Mahdi as a person who will bring salvation to the world, by the grace of God, and everybody, once he comes, will become a true Muslim, and no injustice will be done. Everybody will be in good health, prosperity and well-being.”

Over the centuries there has been no shortage of Muslims who have declared themselves to be the Mahdi, “the guided one.” Historically perhaps the most famous was Muhammad Ahmad, a Sudanese sheikh who in 1881 led an uprising against the Egyptian authorities in Sudan. His warriors seized Khartoum in 1885, massacring many of the inhabitants and beheading the British general Charles Gordon, an episode captured in the 1966 film “Khartoum,” starring Charlton Heston as Gordon and Laurence Olivier as the Mahdi.

But there is no mention of the Mahdi in the Qur’an, and scholars are divided over the meaning of the several passages in the hadith in which the figure is mentioned. The theologian and Qur’anic scholar Javed Ahmad Ghamidi has written that although in some interpretations the coming of the Mahdi is regarded as a sign of the imminent Day of Judgment, “the narratives of the coming of the Mahdi do not conform to the standards of hadith criticism set forth by the muhaddithun (hadith scholars).”

Some of these narratives are weak, and some are fabricated, while others refer only to the coming of “a generous caliph” and, “if they are deeply deliberated upon, it becomes evident that the caliph they refer to is (the 8th-century) Omar ibn Abdulaziz, who was the last caliph from a Sunni standpoint.”

This prediction of the Prophet, wrote Ghamidi, had therefore come to pass, and “one need not wait for any other Mahdi now.”

Regardless, Juhayman and his group were set on a path that would lead to tragedy, reaching out to potential recruits both inside and outside the Kingdom. “Through their correspondence and preaching, they managed to recruit a few individuals,” Prince Turki said.

One temporary recruit was the Saudi writer Abdo Khal, who in 2010 won the International Prize for Arabic Fiction for his novel “Throwing Sparks.” In an interview in 2017 with MBC television, he said that when he was 17 he was one of Juhayman’s men and had even helped to spread the group’s ideology by distributing leaflets.

“It’s true, I was going to be part of one of the groups that was going to enter the Haram,” he said and, were it not for the intervention of his elder sister, he might have found himself among those who were to seize the Grand Mosque.

“I was supposed to move out to (a mosque) where our group was gathering. We were supposed to be in seclusion at the mosque for three days, and we were supposed to leave with Juhayman on the fourth day.”

But his sister stopped him going to the rendezvous point, on the ground that he was too young to be sleeping away from home for three nights. Almost certainly, she saved his life. “And then, on the fourth day, the horrendous incident happened.”

Saudi journalist Nasser Al-Huzaimi, who at one point was also a member of Juhayman’s movement, has written about how the Salafist group, which formerly had been run by “mature and wise” leaders, had been taken over in 1977 by younger members, chief among whom was Juhayman.

“He became the leader and organizer of the group and recruited young members to obey him blindly,” Al-Huzaimi wrote in a series of articles published in the newspaper Al-Riyadh in 2002-2003.

“I do not deny that I was part of this uneducated group that obeyed (Juhayman) blindly and was startled by his personality and words.”

Like Khal, Al-Huzaimi had also helped to distribute seditious leaflets written by Juhayman, which were printed in Kuwait, smuggled into the country and stored in farms for distribution across the Kingdom. But he did not believe in the coming of the Mahdi, nor did he play a part in the attack on the mosque and the “atrocities that endangered us and our society.”

Writer Mansour Alnogaidan was only 11 years old when the siege happened, but like many Saudis of his generation, he felt the tug of various Salafi groups in his youth. Now general manager of Harf and Fasela Media, which operates counter-terrorism websites, he has done extensive research on the Makkah siege.

In an interview with Arab News, Alnogaidan said there were a number of reasons behind the 1979 incident, "including an existing idea and desire in the mind of Juhayman and his group that they were the successors of a Bedouin movement by the name of Ikhwan-men-taa-Allah.

“Some believed they had a vendetta against the Saudi government. Another issue was essentially the personal desires of certain people (such as Juhayman) who sought power and control. He wanted to satisfy something inside him.”

Writer Mansour Alnogaidan speaks about Juhayman's motivations.

Writer Mansour Alnogaidan speaks about Juhayman's motivations.

Juhayman and his group were on the radar of the security services. Over time, recalled Prince Turki, “there were many attempts by authorized religious scholars in the Kingdom to rectify the group’s beliefs by discussion, argument and persuasion.”

Occasionally individuals were taken in for questioning by the authorities “because they were considered to be potentially disruptive to society. Once they were taken in, however, they always gave affidavits and signed assurances that they would not continue with the preaching and so on.”

But “once they were released, of course, they returned to their previous ways.”

At some point in the closing months of the 13th Islamic century, Juhayman’s group identified one of their number, Juhayman’s brother-in-law Mohammed Al-Qahtani, as the Mahdi.

In the early hours of Tuesday, Nov. 20, 1979, as the inhabitants of Makkah and the pilgrims who had lingered after Hajj gravitated toward the Grand Mosque for the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to experience the dawning of a new century in Islam’s holiest place, the stage was set for the most unholy of outrages.

Carrying firearms within the Grand Mosque was strictly forbidden; even the guards were armed only with sticks. An armed assault on the precincts of the mosque — on the sacred values it enshrined for the world’s two billion Muslims — was unthinkable.

But on the first day of the Islamic new year of 1400, the unthinkable happened.

The village of Al-Mundassah, 35 kilometers outside Makkah, was Juhayman's last location before the attack on the Grand Mosque. Rashed Al-Shashai

Crowds on a pilgrimage surround the Kaaba in July 1889. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Crowds on a pilgrimage surround the Kaaba in July 1889. Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Pilgrims in the Safa-Marwa gallery in 1965. Keystone Features/Getty Images

Pilgrims in the Safa-Marwa gallery in 1965. Keystone Features/Getty Images

The Fatah Gate, near where Juhayman's group drove pickup trucks through an entrance used by construction workers. Haramain Archives

The Fatah Gate, near where Juhayman's group drove pickup trucks through an entrance used by construction workers. Haramain Archives

The village of Al-Mundassah, 35 kilometers outside Makkah, was Juhayman's last location before the attack on the Grand Mosque. Rashed Al-Shashai

The village of Al-Mundassah, 35 kilometers outside Makkah, was Juhayman's last location before the attack on the Grand Mosque. Rashed Al-Shashai

'Position the snipers! Close the doors!'

A hostile takeover during the dawn prayer

Prince Turki Al-Faisal describes how Juhayman Al-Otaibi and his group took people by surprise, including security.

Prince Turki Al-Faisal describes how Juhayman Al-Otaibi and his group took people by surprise, including security.

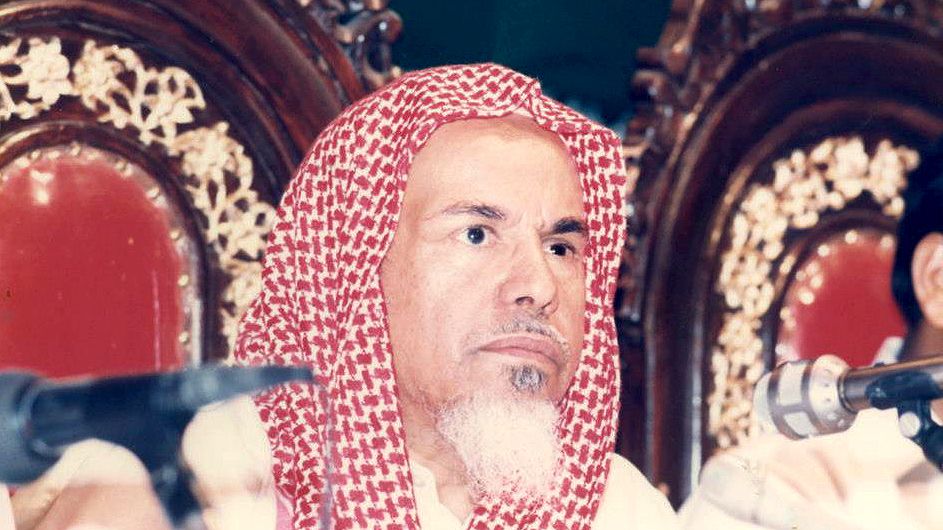

"While I was praying I saw dozens of armed men coming towards the Kaaba," said the imam, Sheikh Mohammed Al-Subayil, in a 2012 interview shortly before he died.

"While I was praying I saw dozens of armed men coming towards the Kaaba," said the imam, Sheikh Mohammed Al-Subayil, in a 2012 interview shortly before he died.

Tuesday, Nov. 20, 1979. The first shots rang out across the courtyard moments after the imam, 55-year-old Sheikh Mohammed Al-Subayil, had finished conducting fajr, the first prayer of the day and the first of the new century.

"While I was praying I saw dozens of armed men coming towards the Kaaba," said the imam, Sheikh Mohammed Al-Subayil, in a 2012 interview shortly before he died.

It was a little after 5:15 a.m. Moments earlier, the imam and the 100,000 or more worshippers in the Grand Mosque had been focused on their devotions in Islam’s holiest sanctuary.

Now the sanctity of a place sacred to Muslims all over the world was about to be desecrated by a gang of armed men determined to use violence to drive Saudi Arabian society back into the Middle Ages.

The call to the first prayer had summoned pilgrims from far and wide to the courtyard of the Grand Mosque. Worshippers stood side by side, forming a circular formation around the Kaaba as they welcomed the dawn of the new Islamic century.

Some were locals, others were visitors who had concluded their Hajj pilgrimage two weeks earlier and had delayed their departure to take part in this once-in-a-lifetime event, before bidding farewell to a place that for centuries had seen countless millions like them come and go.

But among their number was a group of fanatics the like of which the Holy Mosque had never seen before.

In rare interview footage preserved by the King Abdul Aziz Archive and Research Center, recorded in 2012, shortly before his death, Al-Subayil recalled the moment the awful truth dawned on him.

Having taken up the imam’s position in front of the Kaaba, Al-Subayil conducted the dawn prayers. At first, “I did not sense anything bad, but while I was praying I saw dozens of armed men coming toward the Kaaba,” he said. His confusion turned to consternation as gunshots rang out in the courtyard behind him.

The siege of the mosque had claimed its first victims — two unarmed police guards gunned down at their posts.

As chaos ensued and the worshippers began to disperse, some managing to flee from the mosque in the confusion before the gates were closed by the attackers, three armed men pushed their way through the crowd toward the imam. One, dressed in a short, ragged traditional dress, took the microphone and began issuing orders over the mosque’s loudspeakers.

“Get on the minarets! Position the snipers! Close the doors! Deploy the guards! Position the guards and sentinels in front of the doors!”

Hear the moment when Juhayman's men seized the imam's microphone, from Dirk van den Berg's documentary "The Siege of Mecca."

Hear the moment when Juhayman's men seized the imam's microphone, from Dirk van den Berg's documentary "The Siege of Mecca."

It was the ring-leader, Juhayman Al-Otaibi. Then he handed the microphone to another man, and what he had to say shocked the imam and all who heard it.

The Mahdi, in the shape of Mohammed bin Abdullah Al-Qahtani, had arrived to wipe the world of its evils and was here among the armed men who had seized the mosque and were now locking inside 100,000 pilgrims and residents. The speaker rejected the authority of the Saudi royal family and the ulema, the senior theologians of Islam, as illegitimate. Now everyone present, he said, must come forward to swear the oath of allegiance to the Mahdi.

“We have no sin except calling people to return to the Qur’an and hadith and apply their instructions even if that was against the government and high-ranking sheikhs,” the speaker said, according to a local Arabic newspaper. “The one to whom we will pledge allegiance today is Mohammed bin Abdullah, who is from Quraish. His father and his mother are Ashraf … they are descendants of Hussein bin Ali and (his wife) Fatima, may Allah be pleased with them, and all the qualities mentioned in the hadiths apply to him.”

The man himself, carrying an automatic weapon, then stepped forward. He stood near the Kaaba, as the false prophecy adopted by the renegades had predicted the Mahdi would. Juhayman’s men first took it in turns to swear their oath of allegiance and then began forcing the captive worshippers to follow suit.

In the confusion, the imam blended into the crowd and made his way to his office in the mosque. There, he called Sheikh Nasser bin Hamad Al-Rashid, president of the General Presidency for the Affairs of the Two Holy Mosques, and told him what was going on — and held the phone up so he could hear the gunshots that were ringing out.

Al-Subayil realized that the terrorists were allowing foreign pilgrims to leave the mosque, but were keeping anyone of a Saudi appearance hostage, so after lying low for about four hours he decided to try to escape.

“I went down to the door of the basement,” he recalled. Taking off his distinctive cloak, “I passed between the two gunmen who were in the lobby with my head down, and by hiding among Indonesian pilgrims I was able to get out.”

At first, the official response to the wholly unanticipated outrage was confused. “When these individuals took over the mosque, the first people to deal with them were the mosque police, who at that time were simply unarmed, and there to direct people where to go rather than to enforce security,” said Prince Turki.

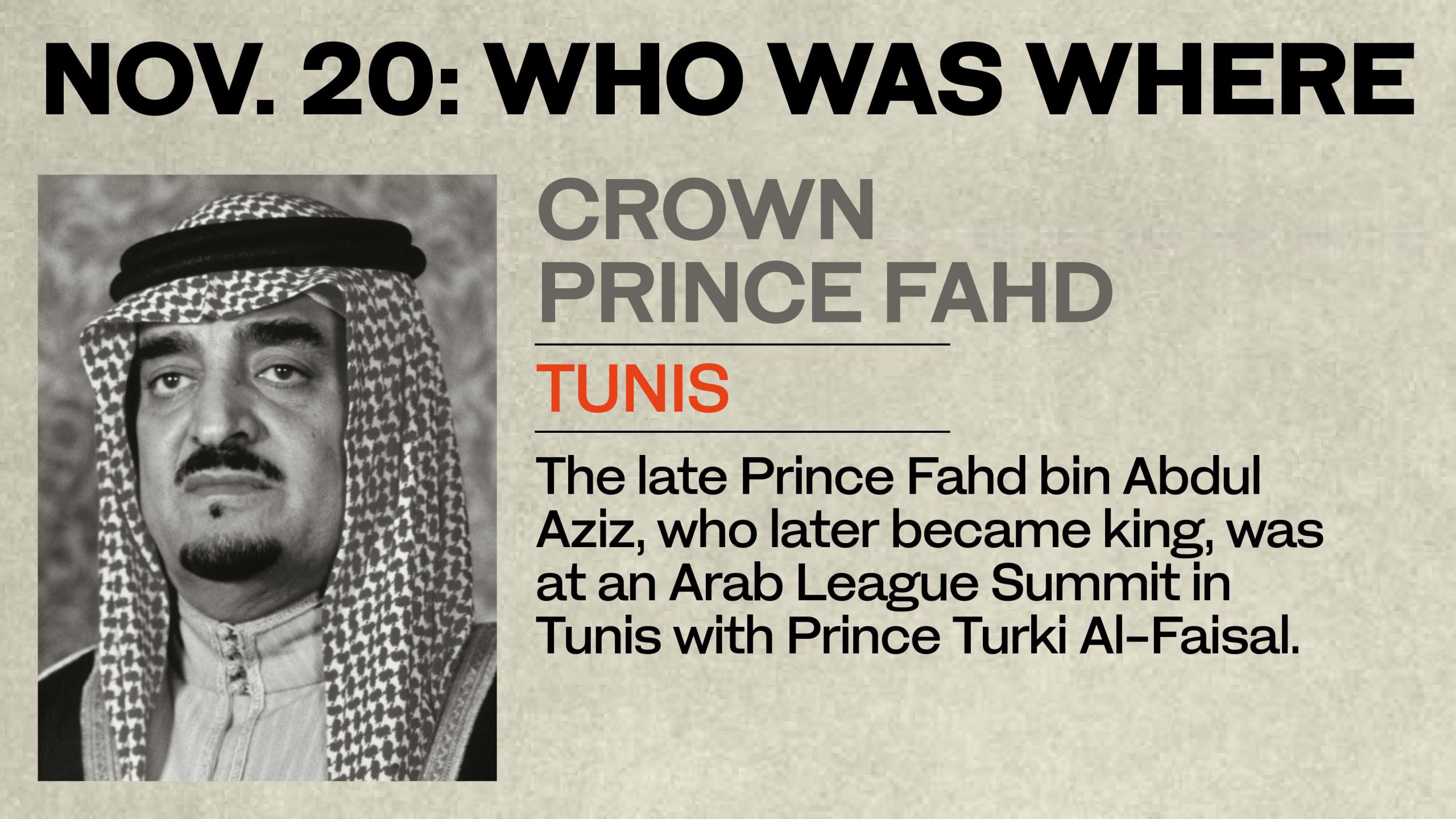

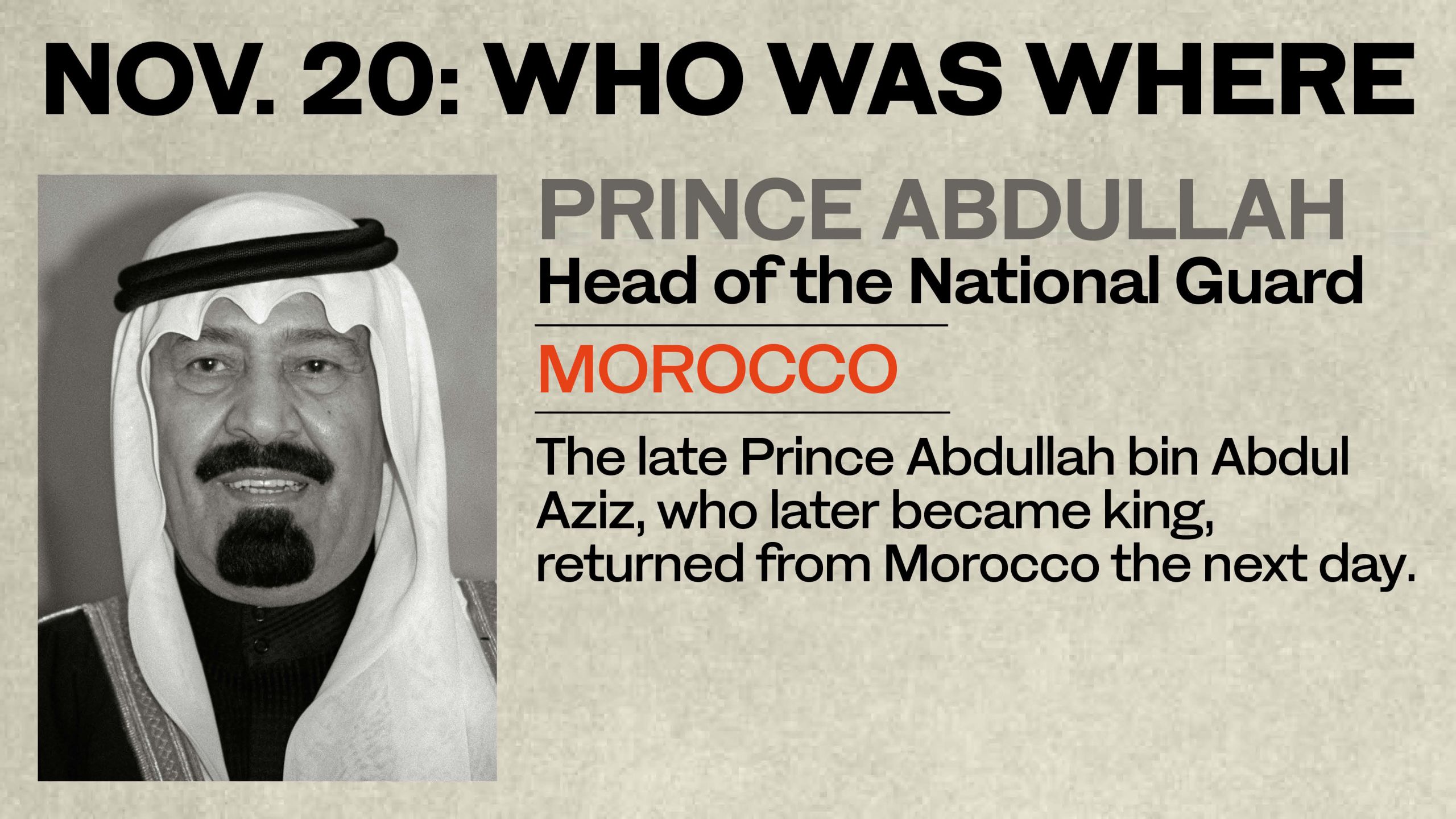

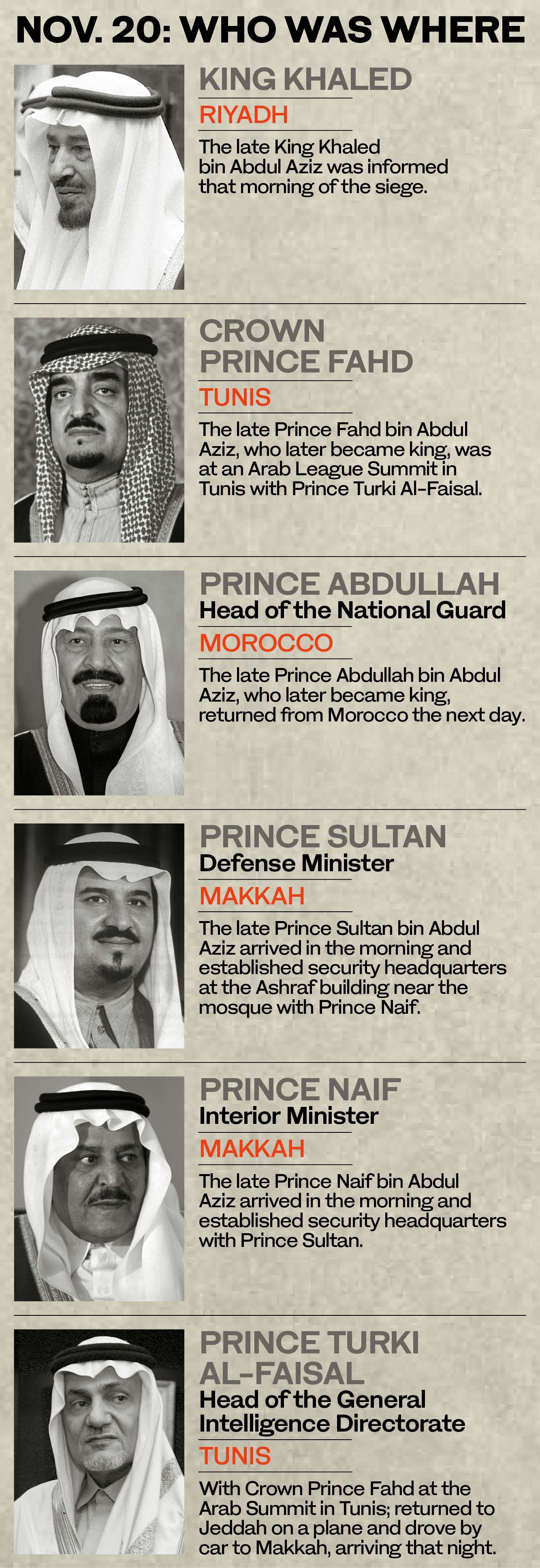

“Everybody inside and outside the mosque was taken by surprise,” recalled the prince, who at the time of the attack was in Tunis, attending an Arab League summit with Crown Prince Fahd bin Abdul Aziz. Prince Abdullah bin Abdul Aziz, then head of the National Guard, was in Morocco.

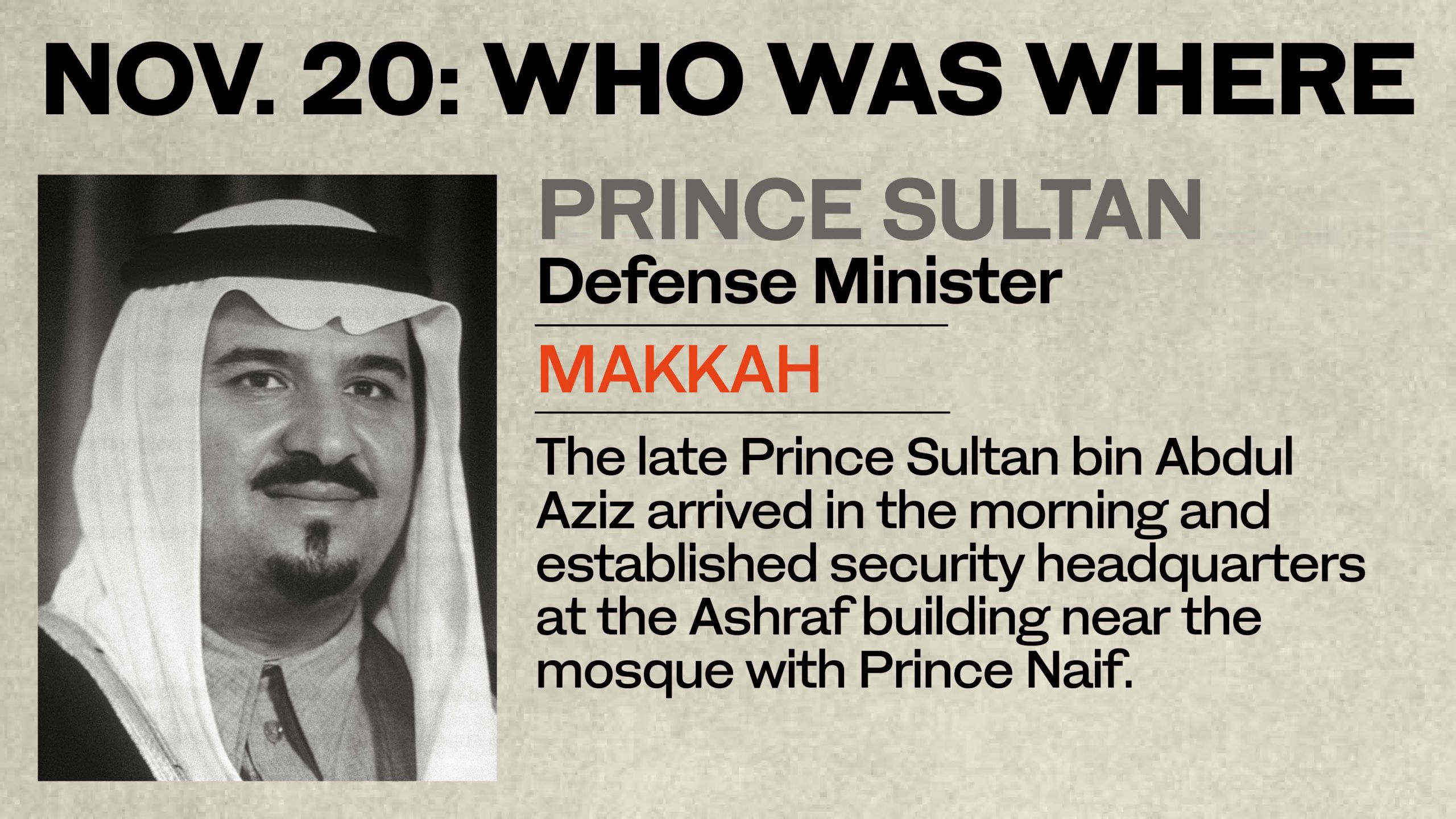

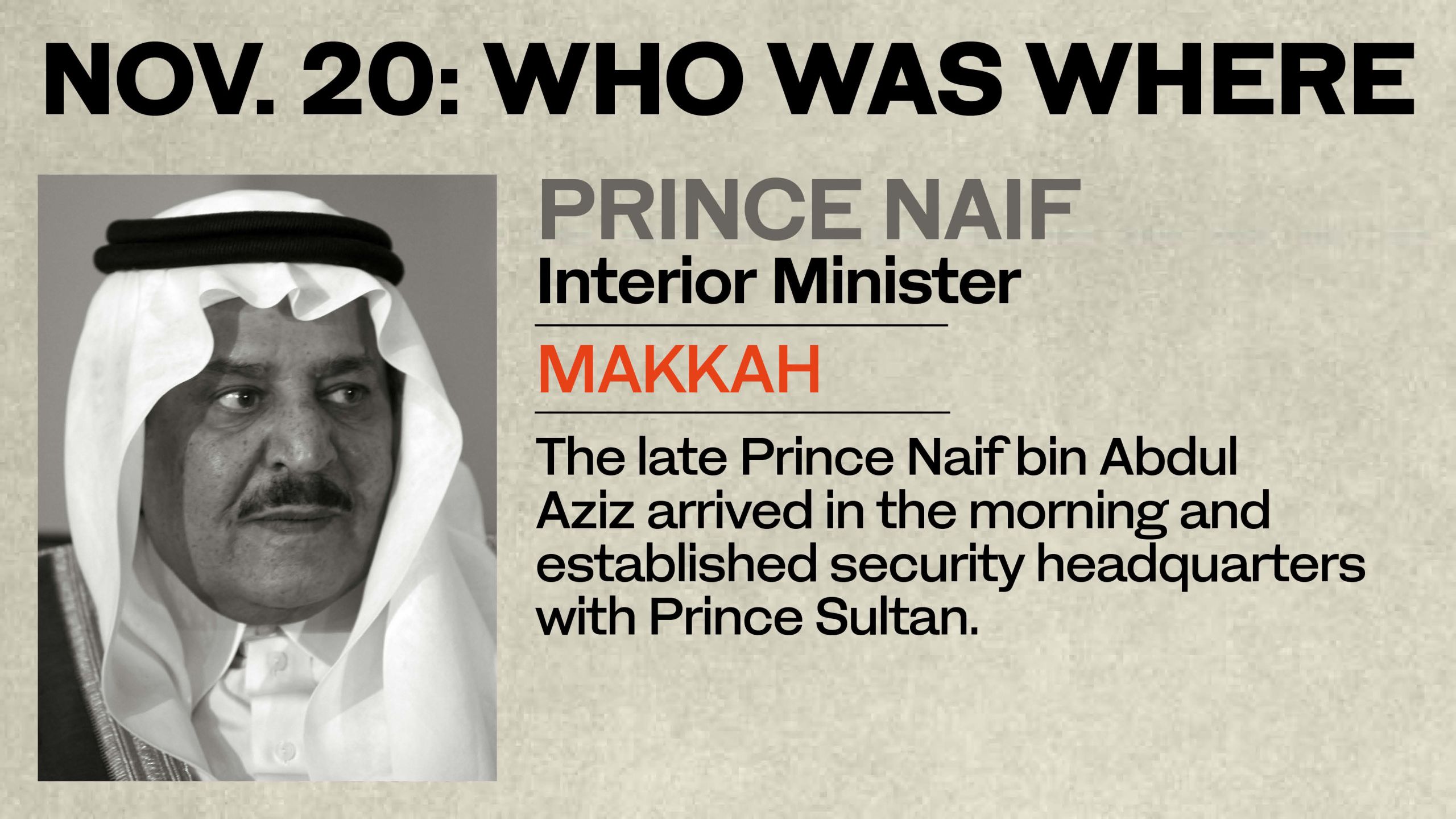

An early-morning phone call from Sheikh Nasser, the senior cleric in charge of Makkah and Madinah, woke King Khaled to the news that the mosque had been seized. The king immediately ordered two senior members of the government, Defense Minister Prince Sultan bin Abdul Aziz, and Interior Minister Prince Naif bin Abdul Aziz, to assess the situation on the ground.

By 9 a.m. they had joined Makkah’s regional governor, Prince Fawwaz bin Abdul Aziz, in the holy city. Prince Turki, meanwhile, was on the first plane back to Jeddah. In Makkah the National Guard and the Saudi Army had begun arriving at the mosque in force.

Juhayman’s group, Prince Turki recalled, “had not been given attention security-wise because they were not thought to be a cause for danger, because of their small number and also because nobody believed that anyone would fall for this idea of a Mahdi.”

Exactly how much of a danger they posed, however, had become brutally clear by about 8 a.m., when a lone police officer approaching the mosque in a jeep was wounded by sniper fire. Minutes later, a fusillade of fire from snipers posted on rooftops and in minarets greeted more officers who arrived on another side of the mosque, killing eight and wounding 36 more.

See the deadly gunfire from the minarets in footage obtained from "The Siege of Mecca."

See the deadly gunfire from the minarets in footage obtained from "The Siege of Mecca."

The behavior of the militants appalled all who witnessed it. According to Sheikh Hammoud Oqayl, the imam of Riyadh’s Malazz Mosque, whose interview by a local newspaper on Dec. 4, 1979, was quoted in Arab News, witnesses claimed that the attackers had used hostages as human shields and opened fire on curious citizens who gathered on the hills overlooking the mosque. A young boy was killed by the indiscriminate fire.

They also shot at anyone who tried to recover the bodies of the dead outside the mosque. In one incident, one of Juhayman’s snipers in a minaret had been shot dead by the security forces outside the mosque and was callously pushed to the ground from the balcony by his compatriots. One of the soldiers “valiantly moved forward to move the body of the dead man from the battlefield,” reported Arab News on Dec. 5. “He was shot, and his body fell on that of the dead renegade.”

It later emerged that weapons, ammunition and food had been smuggled into the mosque before the siege, and in the most macabre fashion. Some guns had been hidden in large construction containers. But others, taking advantage of the tradition of Islamic funeral prayers conducted by the imam within the sacred mosque, had been concealed in coffins.

“Using coffins of the dead to smuggle arms into the Grand Mosque — who could have thought of exploiting this?” said Rashed Al-Shashai, an artist who as a young boy heard tales of the siege from his grandfather, who worked at the mosque and narrowly avoided being taken hostage.

“How could they take advantage of this? Even if there had been hundreds of people searching (people at) the gates of the mosque, it is impossible for anyone to search the dead in front of his family.”

Inside the mosque, fear and confusion reigned. Juhayman’s men had begun allowing some of the hostages to leave, but it was clear that they had no intention of freeing any Saudis. Many were forced to swear allegiance to the so-called Mahdi.

With others, Al-Shashai’s grandfather moved toward the north of the mosque. As the infamous Mahdi “sermon” blared out of the speakers and occasional shots rang out, they hid behind pillars and looked for a way out.

Hear one of the messages of Juhayman's group blaring out from the speakers.

Hear one of the messages of Juhayman's group blaring out from the speakers.

“They had one of two choices,” said Al-Shashai. “Either they believe in the salvation of Juhayman or believe in their own salvation, search for it themselves and get out of the dilemma they found themselves in.”

They chose the latter and continued moving from one pillar to the next, heading toward the northern end of the Safa-Marwa gallery. It was here that several people, including Al-Shashai’s grandfather, were able to make their escape.

“At the end of the corridor they found a mosaic design on the windows, and in its center was a large Islamic design of an eight-pointed star. Through this star, those who were thin and small-built were able to escape. This star was their salvation.”

To this day the star, a symbol of salvation, is a motif Al-Shashai uses in his art.

Saudi artist Rashed Al-Sashai's "Salvation 2" is inspired by the same octagram-shaped opening in the Safa-Marwa gallery through which his grandfather escaped.

Saudi artist Rashed Al-Sashai's "Salvation 2" is inspired by the same octagram-shaped opening in the Safa-Marwa gallery through which his grandfather escaped.

Saudi artist Rashed Al-Shashai tells the story of his grandfather's escape on Nov. 20, 1979.

Saudi artist Rashed Al-Shashai tells the story of his grandfather's escape on Nov. 20, 1979.

By now the courtyard of the Grand Mosque, normally teeming with worshippers by this time on the first day of the new year, was eerily empty. Juhayman’s men had forced men, women and children into the corridors of the mosque, and the silence was broken only by the crack of bullets as snipers fired on the surrounding security forces.

Late that evening, Prince Turki arrived in Jeddah after his flight from Tunis and drove the 70 kilometers to Makkah. His destination was the Shoubra Hotel, just south of the mosque’s King Abdul Aziz Gate, where senior members of the authorities were gathering. Waiting there to brief him with other officials and members of the royal family were Defense Minister Prince Sultan and Interior Minister Prince Naif.

Prince Turki stepped out of his car and approached the hotel. As he put his hand out to open the door a bullet flew past him and shattered the glass. Miraculously, he was unharmed and hurried inside the building.

Almost certainly the bullet had been fired by a sniper positioned in one of the twin 89-meter-tall minarets that flanked the King Abdul Aziz Gate — a straight shot over open ground of no more than 150 meters. The head of Saudi Arabia’s General Intelligence Directorate had had a very lucky escape. Within a short time, a command center was set up in the tallest building near the mosque, the Al-Ashraf Tower north of the Marwa Gate.

'Forces of the angels'

The battle to recapture Makkah's Grand Mosque

Watch Saudi troops enter the mosque in this footage from Dirk van den Berg's "The Siege of Mecca."

Watch Saudi troops enter the mosque in this footage from Dirk van den Berg's "The Siege of Mecca."

A Saudi Army vehicle in a state of alert outside the Grand Mosque. Asharq Al-Awsat

A Saudi Army vehicle in a state of alert outside the Grand Mosque. Asharq Al-Awsat

Demonstrators in 1979 outside the American Center in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, alleging American and Israeli involvement in the takeover of the Grand Mosque. Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

Demonstrators in 1979 outside the American Center in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, alleging American and Israeli involvement in the takeover of the Grand Mosque. Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

The basement after Juhayman's men were captured: The twisted ceiling fan and bullet-riddled walls show the extent of the struggle.

The basement after Juhayman's men were captured: The twisted ceiling fan and bullet-riddled walls show the extent of the struggle.

A Saudi trooper in a gas mask showing a basket of dates from the militants' stocks in the Qaboo. Asharq Al-Awsat/Haramain Archives

A Saudi trooper in a gas mask showing a basket of dates from the militants' stocks in the Qaboo. Asharq Al-Awsat/Haramain Archives

Saudi soldiers search through the rubble in the basement of the Grand Mosque. Muhammad Ibrahim/Asharq Al-Awsat

Saudi soldiers search through the rubble in the basement of the Grand Mosque. Muhammad Ibrahim/Asharq Al-Awsat

Royal Saudi Air Force helicopter pilot Col. Mahdi Al-Zwawi was in Riyadh when in the early hours of new year’s day he was recalled to his base in Taif, some 90 kilometers from Makkah.

He took the next available commercial flight and by 6 a.m., still in the dark about what had happened at the Grand Mosque, was on his way. “In those days we did not have social media,” he said. “There was nothing peculiar at Riyadh airport, and I did not sense that something of high importance had happened.”

"My colleagues and I, and I guess every citizen, wished to go and sacrifice himself in defense of the Grand Mosque," said Col. Mahdi Al-Zwawi. Supplied

"My colleagues and I, and I guess every citizen, wished to go and sacrifice himself in defense of the Grand Mosque," said Col. Mahdi Al-Zwawi. Supplied

His first clue that something out of the ordinary was going on came when he arrived at Taif regional airport and noticed there were no taxis. Mere hours after the mosque had been seized, the extent of the insurrection was still unclear and for security reasons taxis had been prevented from entering airports.

A car was sent by his squadron to pick him up. When he arrived at the nearby RSAF base he found that “everybody was confused — nobody knew what exactly was going on.”

Eventually, the truth became clear and Al-Zwawi and his fellow pilots were shocked — and eager to do what they could. “We learnt that a terrorist group had entered the Grand Mosque and started killing pilgrims,” he recalled.

“This is the country of security and safety, the country of Islam. Our rulers’ favorite title is ‘Servant of the Two Holy Mosques’ and we are like them — servants of the visitors of God.

“Then all of a sudden, a group from among us would kill and beat them — why? For what? What was the guilt of any pilgrim?”

The news, he said, was shocking, “not only for us, but also for all Muslims around the globe. I felt that we were all tied up (in this), each one of us ... My colleagues and I, and I guess every citizen, wished to go and sacrifice himself in defense of the Grand Mosque.”

Al-Zwawi’s wish was very nearly granted.

The authorities, scrambling for intelligence so that they could put together a response, ordered his helicopter unit to fly constant reconnaissance flights during daylight hours over the mosque, a hazardous task that they would keep up for the next two weeks.

Flying at about 300 meters over the mosque for the first time, Al-Zwawi was struck by the unprecedented absence of worshippers in the great courtyard. Later on, flying lower, “we saw people in the minarets trying to shoot at us.” At one point he spotted two heavily armed women crossing the courtyard, wearing traditional dress but carrying automatic rifles.

During one reconnaissance flight, Al-Zwawi noticed that his high-frequency long-range radio had stopped working. After he returned to base and reported the fault, a technician called him over. A sniper had hit and destroyed the radio “and the bullet was 12 to 15 centimeters away from the fuel tank. So, a slight move from the sharpshooter would have been fatal for us and for the aircraft. But, thank God, we were saved.”

Col. Mahdi Al-Zwawi, a native of the city of Makkah and a retired Air Force helicopter pilot, describes what he saw flying reconnaissance missions during the siege.

Col. Mahdi Al-Zwawi, a native of the city of Makkah and a retired Air Force helicopter pilot, describes what he saw flying reconnaissance missions during the siege.

Back in Makkah, the information gathered by Al-Zwawi’s squadron was being added to intelligence gleaned on the ground as the authorities began to piece together the picture of what was happening.

“Most important was to try to keep a clear head as to what is to be done, and as much as possible to minimize the negative or the fatal consequences of the shooting of weapons, as had happened on the first day,” Prince Turki told Arab News.

“Some deaths had already occurred inside the mosque, but also (among the) security forces, who tried to liberate it.”

The most pressing task was “to try to get information about what was happening inside the mosque. Fortunately, some of the people who had left before the doors were closed described what had happened and gave estimates as to the number of people inside.”

Those numbers, which ranged from 50 to 100 insurgents, proved to be an underestimate — no one person who had escaped from the sprawling site of the mosque, a warren of rooms and spaces over many levels, could possibly have seen all the intruders.

What all agreed on, however, was that the terrorists were well armed and had plenty of ammunition and food — clearly, they had come prepared for a long siege.

And there was something else.

“They also had with them family, wives and children, whom they brought into the mosque with them,” recalled Prince Turki. “That added another complication as to what should or should not be done.”

The first order of business for the authorities was to summon members of the ulema, the primary theologians of Islam, to a meeting with the king in Riyadh.

The Prophet had been clear — fighting in the mosque was strictly forbidden. Before force could be used to retake it, the ulema would have to deliver a fatwa declaring it lawful.

While the ulema deliberated, the next two days were spent in feverish planning, bringing in armored vehicles and other hardware, and tracking down accurate plans of the mosque.

“That took some time,” recalled Prince Turki. Many of the plans had to be unearthed from archive storage in Makkah and Jeddah.

At 5 a.m. on Wednesday, Nov. 21, the second day of the siege, Riyadh Radio broadcast a short announcement by the Interior Ministry, stating that a group of armed “renegades to the Islamic religion” had infiltrated the mosque and “presented one of their number to the crowds of Muslims inside the Holy Mosque to lead the dawn prayers, claiming that he was the promised Messiah.”

Word about events in Makkah had, however, already been leaked to the international media via Washington sources, and on the siege’s second day the front page of The New York Times carried the wholly erroneous — and highly dangerous — headline: “Makkah mosque seized by gunman believed to be militants from Iran.”

Following events in Iran, where the shah had been overthrown and replaced by a fundamentalist Islamic republic headed by the revolutionary cleric Ayatollah Khomeini, the Islamic world was a potential time bomb. On Nov. 4, just 16 days before the mosque was seized, Iranian revolutionaries had attacked the US embassy in Tehran, taking captive 52 Americans who would be held hostage for 444 days.

Inevitably, conspiracy theories about the events in Makkah began to circulate, fueled not only by The New York Times’ coverage but also by Khomeini, who publicly offered the alternative speculation that “this act has been perpetrated by the criminal American imperialism so that it can infiltrate the solid ranks of Muslims.”

A New York Times headline erroneously attributed the attack to Iran.

A New York Times headline erroneously attributed the attack to Iran.

Demonstrators in 1979 outside the American Center in Rawalpindi, Pakistan, alleging American and Israeli involvement in the takeover of the Grand Mosque. Granger Historical Picture Archive / Alamy Stock Photo

On Wednesday, Nov. 21, a mob in Pakistan infuriated by Khomeini’s statement stormed the US embassy in Islamabad, burning it to the ground. Two US servicemen and two Pakistani members of the embassy staff died in the attack. On Dec. 2, similar unrest inspired by Khomeini’s false allegations flared up in Tripoli, where the US embassy was burned and all personnel were withdrawn from Libya for the next 25 years.

On Thursday, Nov. 22, Interior Minister Prince Naif moved to quash the rumors with a categorical statement: “Neither the United States, Iran, nor any other countries have had anything to do with the attack on the Holy Kaaba.” The attack had been carried out solely by “a gang that deviated from the path of Islam.”

Back in Makkah, after attempts over several days to gain access to the mosque through a number of entrances proved unsuccessful, the decision was made to force entry through the Marwa Gate at the north end of the Safa-Marwa gallery. The 380-meter-long covered passageway that connects the two hills between which pilgrims must travel seven times as part of Hajj rituals was wide enough to accommodate armored personnel carriers.

By this time, command of the operation to retake the mosque had been given to Brigadier general Faleh Al-Dhahri, commander of the Saudi Army’s King Abdul Aziz Armored Brigade, who had been asked by Prince Naif to head to Makkah with special equipment from his base at Tabuk. The Marwa Gate doors would be blown open by members of Prince Turki’s own Directorate of Intelligence, allowing the armored brigade to storm in.

A Saudi Army vehicle in a state of alert outside the Grand Mosque. Asharq Al-Awsat

There was, as Prince Turki recalled, a grim irony in the deployment of the armored brigade, which was based more than 800 kilometers away in the northwestern town of Tabuk. “One of the beliefs of these people, along with their belief in the Mahdi and that he would be declared in the mosque, and so on, was that the forces of the devil that would oppose the Mahdi would come from Tabuk.

“It just shows you how incredible the situation was. Eventually forces did come from Tabuk, but they were not forces of the devil but of the angels.”

Abdulaziz Al-Dhahri, the son of Brigadier general Al-Dhahri, allowed Arab News access to his father’s notes documenting the retaking of the mosque.

At the end of the first day of the siege, the first units of the armored brigade transported troops to the walls of the Grand Mosque to probe the defenses, but the snipers made it impossible for them to leave the vehicles.

Abdulaziz Al-Dhahri speaks about his father's role in retaking the mosque.

Abdulaziz Al-Dhahri speaks about his father's role in retaking the mosque.

On day two, however, sharpshooters from the special forces deployed in high buildings around the perimeter of the mosque were able to neutralize at least some of the enemy snipers. Under this overwatch troops were able to approach and inspect every one of the mosque’s entrances. All bar one was found to have been effectively barred by the insurgents — the Marwa Gate at the northern end of the Safa-Marwa gallery.

By late Wednesday, the plans to retake the mosque were in place.

At 3:30 a.m. the following day, Nov. 22, Saudi artillery began targeting the mosque, not with high explosives but with “flash-bang” shells designed to disorientate the militants. Under cover of this bombardment, troops were able to reach the eastern side of the Safa-Marwa gallery. They were hoping to breach the Al-Salam Gate, halfway along the gallery, but were beaten back with the loss of several lives.

Later, Saudi forces succeeded in breaching the Marwa Gate at the northern end of the gallery with explosives, but were cut down as soon as they entered the mosque.

On Friday, Nov. 23, for the first time in centuries, no sermon was preached from the Grand Mosque. By the end of the day, however, the text of the fatwa sought by the king was finally agreed by the ulema. Only if the militants declined an opportunity “to surrender and lay down their arms” could force be used against them in the mosque, a decision that was grounded in Verse 191 of Al-Baqarah, the second chapter of the Qur’an: “And do not fight them at Al-Masjid Al-Haram until they fight you there. But if they fight you, then kill them. Such is the recompense of the disbelievers.”

Now the Kingdom’s hands were untied and the full force of Brigadier general Al-Dhahri’s armored brigade could be unleashed. First, to comply with the fatwa, a call to surrender was broadcast over loudspeakers. When it was ignored, rockets were fired at the minarets, neutralizing the snipers, and artillery blasted an opening in the side of the Safa-Marwa gallery. M113 armored personnel carriers rumbled in through the opening and through the already-destroyed Marwa Gate.

It was not until midday on Saturday, Nov. 24, after hours of desperate fighting and many losses among the troops, that the gallery was finally cleared — but the battle for the mosque was far from over. Driven from the upper levels, Juhayman and the surviving insurgents, along with some hostages and prisoners they had captured, had retreated into the Qaboo, the warren of more than 225 interconnected chambers under the mosque.

Here, equipped with food, water and plenty of ammunition, they would hold out for more than a week, fighting off the security forces with everything from bullets and Molotov cocktails to burning rugs. At one stage the assaulting troops tried to flush out the insurgents with tear gas but this, according to an account in the book “The Siege of Makkah,” based on interviews with Saudi soldiers, “proved a complete fiasco.”

The author of the book, Yaroslav Trofimov, an Asia-based reporter for The Wall Street Journal, reported that the militants blocked the narrow underground passageways with mattresses and wrapped water-soaked headdresses around their faces. The gas, meanwhile, rose back up to the surface, causing more problems for the security forces than the militants.

Juhayman’s men also had a tactical advantage. Several of them had studied at the Grand Mosque and knew every centimeter of the maze. After several attempts throughout the following Monday and Tuesday to penetrate the Qaboo, it became clear that fighting room to room would cost too many lives, and so it was decided to try to drive out the militants with an altogether different type of gas.

On Sunday, Dec. 2, three advisers from France’s elite Groupe d’Intervention de la Gendarmerie Nationale (GIGN) flew into Taif, bringing with them supplies of a chemical called dichlorobenzylidenemalononitrile. CB, for short, was a gas designed to seriously restrict breathing, and which was fatal if breathed in for too long. The French agents, who were not Muslims, could not enter Makkah, but they trained members of the General Intelligence Directorate in how to use it, equipping them with gas masks and chemical suits.

Brigadier general Faleh Al-Dhahri describes the operation's final stage in a TV interview.

Brigadier general Faleh Al-Dhahri describes the operation's final stage in a TV interview.

On the morning of Monday, Dec. 3, holes were drilled in the floor of the mosque and canisters of CB, attached to explosive charges, were dropped into the basement maze. Because of the layout of the interconnected rooms, the tactic was only partially effective and it took more than 18 hours of bitter, bloody fighting before the final stronghold was breached on Dec. 4.

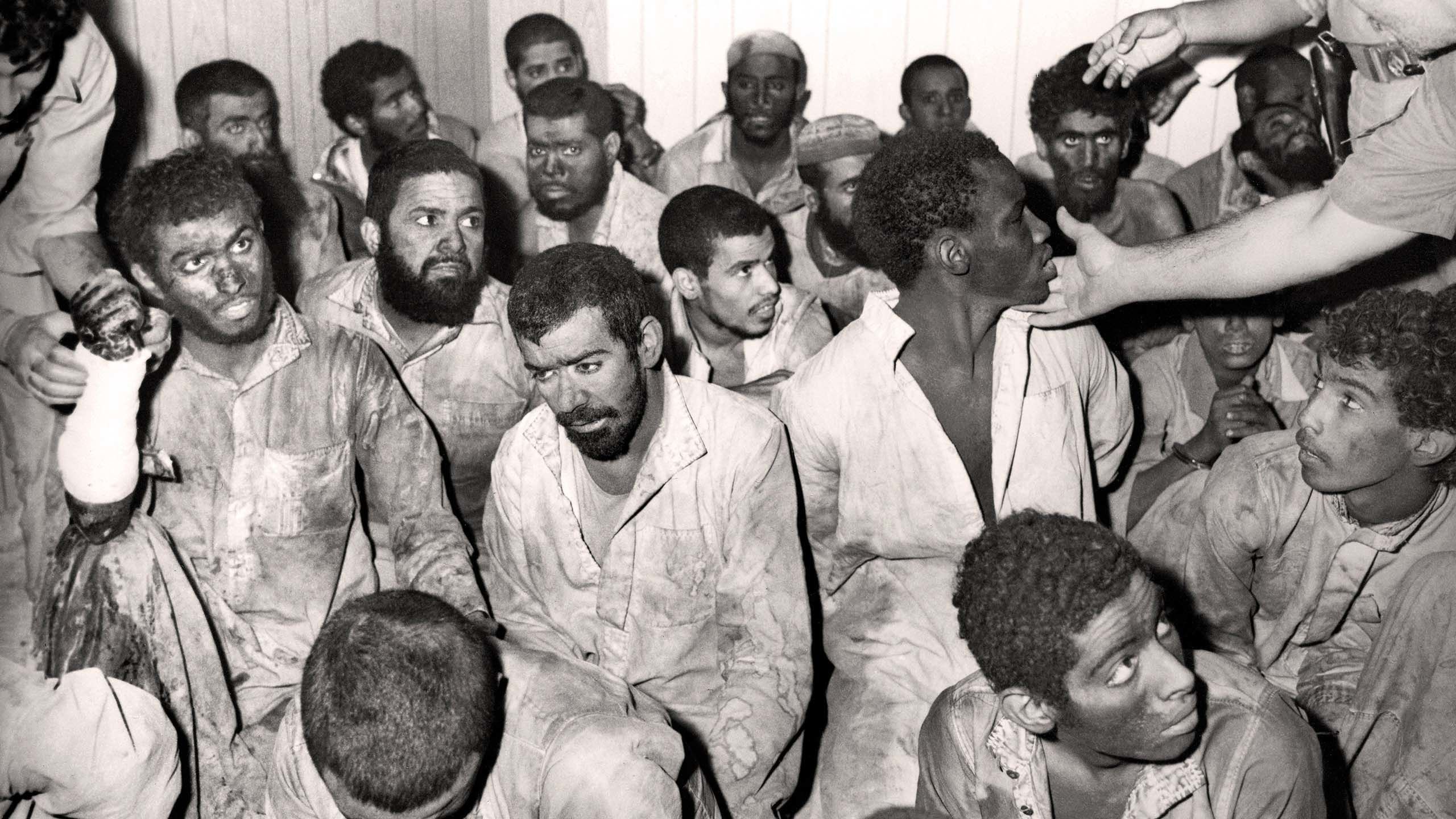

In a room about two meters square were found cowering 20 thoroughly defeated militants, exhausted, hungry and covered with the grime of battle. The morale of the surviving militants may have been gradually weakened when Al-Qahtani was presumed killed on the third day or fourth day of the fighting, believes Al-Dhahri. As the days passed without seeing him, they could no longer hold on to the belief that the Mahdi could not be killed.

“His death changed the morale of the gunmen,” he said. “Afterwards, Juhayman killed or punished anyone who backed out of the operation.”

The troops found the last of the surviving insurgents huddled together, surrounded by the dates, water and labneh (a soft cheese made from strained yogurt) they had smuggled into the mosque along with their weapons. Among them was Juhayman.

Joining the last group to infiltrate, Brigadier general Al-Dhahri recognized him. Mindful of the need to extract as much information as possible from the man who had caused such upheaval and loss of life, he assigned a special squad to ensure his protection and safe passage into captivity.

It was Interior Minister Prince Naif who announced that the siege was over.

“Resistance in the tunnels of the mosque has been totally eliminated,” Arab News reported him saying, adding “the remnants of the corrupt heretics who attacked the Holy Mosque are all either killed or captured.”

In a television address to the nation that evening, during which pictures of Juhayman and the other captured renegades were broadcast, he praised the valor of the troops who had liberated the mosque. Those who had died were “better than all of us because they died in the service of God and the defense of his places.”

The operation, reported in Arab News on Wednesday, Dec. 5, had “ended about 1:30 a.m., almost exactly 15 days after it had begun just after early morning prayers at the Holy Haram on Nov. 20.”

Saudi soldiers search through the rubble in the basement of the Grand Mosque. Muhammad Ibrahim/Asharq Al-Awsat

A Saudi trooper in a gas mask showing a basket of dates from the militants' stocks in the Qaboo. Asharq Al-Awsat/Haramain Archives

Prince Naif had announced on Wednesday morning that as soldiers searched through the rubble, they had discovered the body of Mohammed Al-Qahtani, and a gruesome photograph of the body of the man that the rebels had claimed to be the Mahdi was broadcast on TV the following evening. Exactly how he died remains unclear. Some reports said that he had been dismembered by a grenade on the third day of the fighting and had died in agony over several days before his body was eventually identified by Saudi troops.

Prince Turki, however, is in no doubt that “the so-called Mahdi was shot by Juhayman ... I think they didn’t want him to be captured, according to their beliefs.”

On the Tuesday, hours after the siege had ended, a reporter who provided an eyewitness account for Arab News was allowed to visit the mosque. Outside, he reported, nearby houses that had been evacuated remained empty and guarded by troops. He passed “the shell of a burned-out Jeep, filled with bullet holes.”

Inside, “evidence that a fight had raged was everywhere.” Gates and walls had been demolished and “traces left by the bullets and shells could be seen on walls, doors, and in the few fragments of windows left intact. Even lamps, air-conditioners and fans were twisted into rubble.”

Evidence of the fighting, he reported, “could be seen all over the minarets, including broken columns on their outsides, victims of the battle.”

Allowed briefly into the underground maze where the insurgents had mounted their last stand, “I almost fainted in the thick smoke which was still hanging in the air after the early morning assault on the last renegades.”

As he moved through the tunnels, “I was shocked to see that not even copies of the Holy Qur’an had been spared by the attackers. They had ripped them from the bookshelves of the mosque and set fire to many of them, and there were portions of the holy books lying throughout the basement.”

According to the Dec. 4 interview with Sheikh Hammoud Oqayl, the imam of Riyadh’s Malazz Mosque, quoted in Arab News, he cited witnesses saying the attackers had used the pages of the holy book to burn the faces of their dead compatriots in a bid to frustrate their identification by the authorities.

Accompanied by one of the assault commanders — it was feared the besieged insurgents might have left boobytraps — the reporter moved deeper into the warren. In an account that ran on the front page of Arab News on Dec. 6, he wrote: “Columns which had been delicately laced with marble were now stripped of that glistening mineral and everywhere bent and pockmarked with bullets.”

Flanking the corridors in the basement were “the tiny cubicles where the renegades had hidden out during the final days of the siege, each equipped with a mattress and baskets of dates and plastic bottles of water.”

As he re-emerged into the daylight, the courtyard of the mosque was teeming with members of the security forces. “And then I noticed, in the center of it all, stood the Holy Kaaba — untouched by I don’t know what kind of miracle.”

“I gave thanks to God that the incident was over.”

Prince Turki Al-Faisal explains the plan to take back the Grand Mosque.

Prince Turki Al-Faisal explains the plan to take back the Grand Mosque.

The militants unmasked

Swift justice, followed by a long and painful aftermath

Watch King Khaled's arrival with other senior royals at the reopened mosque.

Watch King Khaled's arrival with other senior royals at the reopened mosque.

Although the siege was over, the repercussions were only just beginning.

On the evening of Wednesday, Dec. 5, King Khaled addressed the nation, thanking God for His support in crushing the “seditious act of sacrilege” and denouncing the renegades and “their sacrilegious act of desecrating the House of God, terrorizing innocent worshippers and shedding blood in the Holy Places.”

As Arab News reported the following day, the King said that it was the duty of every Muslim “to keep the Holy Land secure, pure and safe. We are honored by God to serve the Holy Places.” He went on, reported the paper, to praise “the spirit of the people of Saudi Arabia and their support for the government by word and deed which makes us very proud of them indeed.”

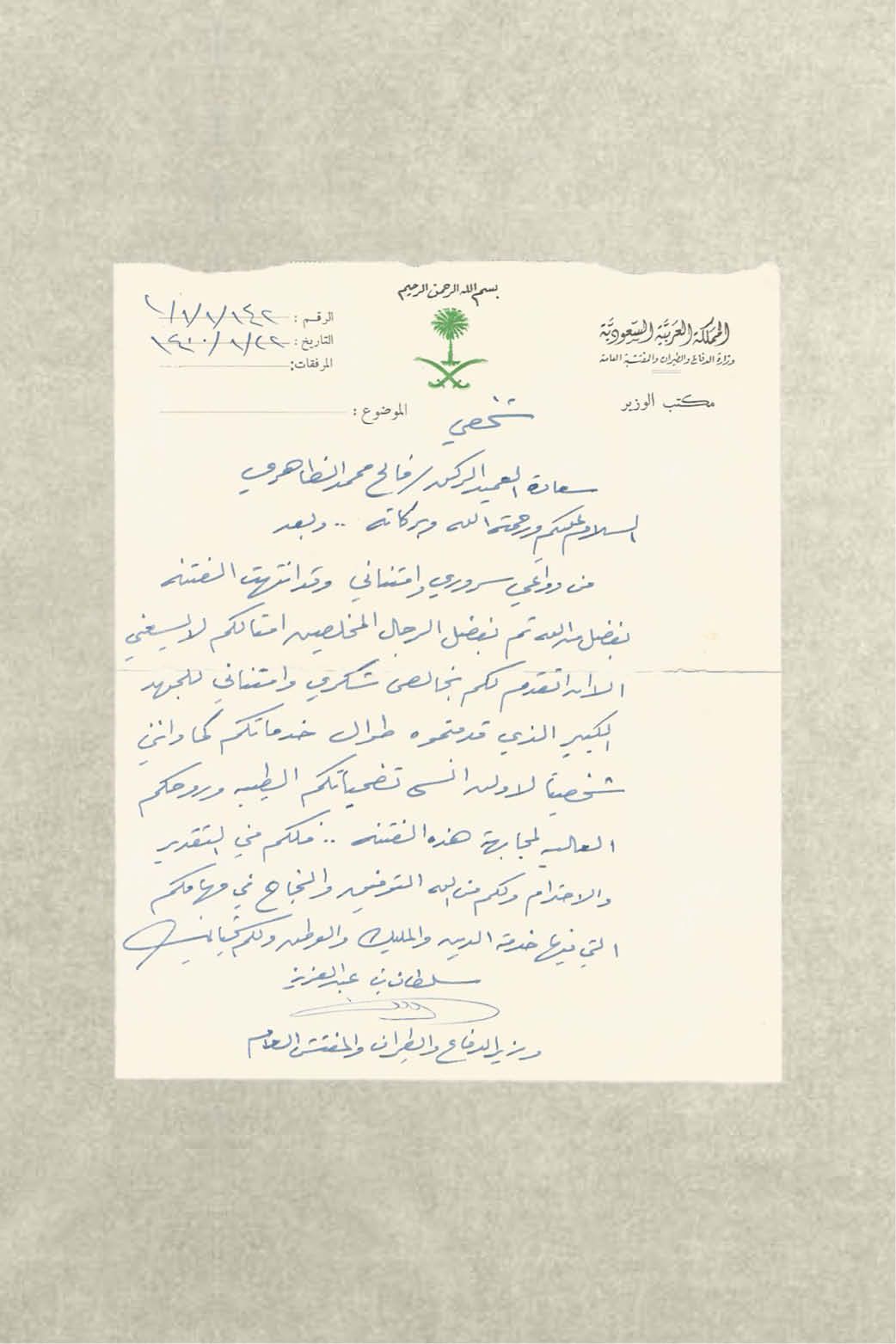

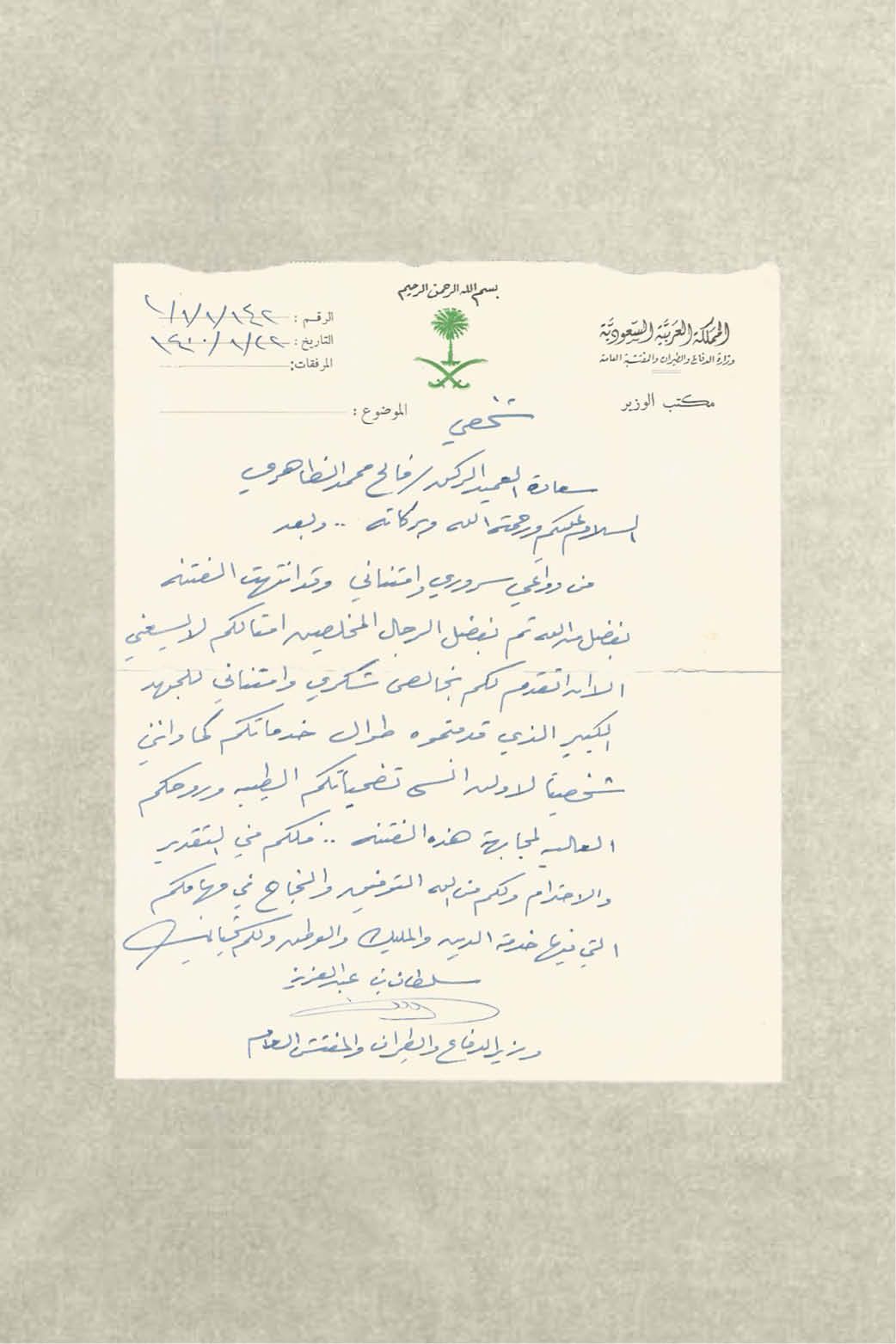

A letter from the late Prince Sultan bin Abdul Aziz to Brigadier general Faleh Al-Dhahri, thanking him for his service and valor.

By a tremendous effort, although bullet holes were still evident in walls and columns around the compound, within two days of the end of the siege the mosque had been returned to a fit state for worship to be resumed.

On Thursday, Dec. 6, King Khaled led joyful worshippers into the courtyard of the mosque, where he kissed the Hajjar Al-Aswad, walked ceremoniously seven times around the Kaaba and sipped Zamzam water from the holy spring.

The following day, the call to Friday noon prayer brought thousands of worshippers to the mosque for the first time in three weeks. Many had camped out all night for a historic ceremony that was broadcast via satellite to other Islamic states.

Then came the reckoning.

The price paid for the liberation of the mosque was a high one — both in number of lives lost and in the dramatic reversal of modernization to which it led, blighting Saudi society for generations to come.

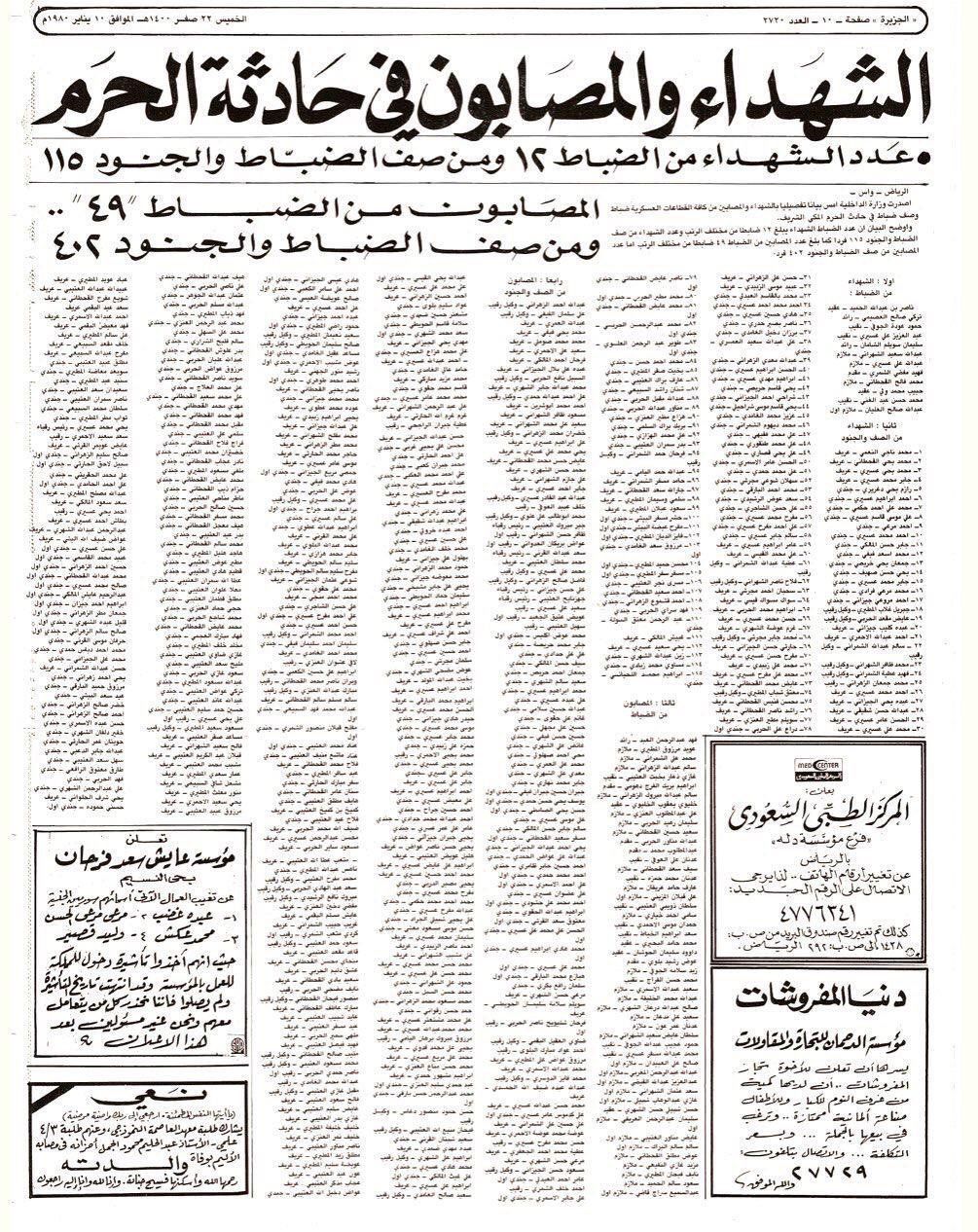

The death toll included 127 members of the forces. Another 451 of their colleagues had been wounded.

Inevitably, although large numbers of hostages had been either released, escaped or were freed by the security forces, some had been caught in the crossfire. The final official toll was 26 dead, including Saudi nationals and pilgrims from Pakistan, Indonesia, India, Egypt and Burma. More than 100 were wounded.

Of the 260 attackers, 117 were dead — 90 died where they fought and 27 others later succumbed to their wounds in hospital.

Saudi newspaper Al-Jazirah carried a list of dead and injured troops.

Saudi newspaper Al-Jazirah carried a list of dead and injured troops.

Justice for the captured survivors was swift. On Jan. 9, 1980, the Saudi Interior Ministry announced that 63 captives had been executed in eight different cities. This, recalled Prince Turki, was “to show that this is a Saudi issue, that the whole country is engaged, not (only) one specific area.”

The executed were 41 Saudi citizens, 10 Egyptians, seven Yemenis, three Kuwaitis, a Sudanese and one Iraqi. The government was at pains to point out that none of the foreigners involved in the attack had acted at the behest of their own governments, but out of misguided personal religious conviction.

Fifteen executions took place in Makkah; 10 were executed in Riyadh; seven each in Madinah, Dammam, Buraidah and Abha; and five each in Hail and Tabuk. The death sentences of 19 militants were reduced to prison terms of varying lengths. Of the 23 women and children captured, the women were sentenced to two years’ imprisonment in a correctional facility, while the children were enrolled in child protective services.

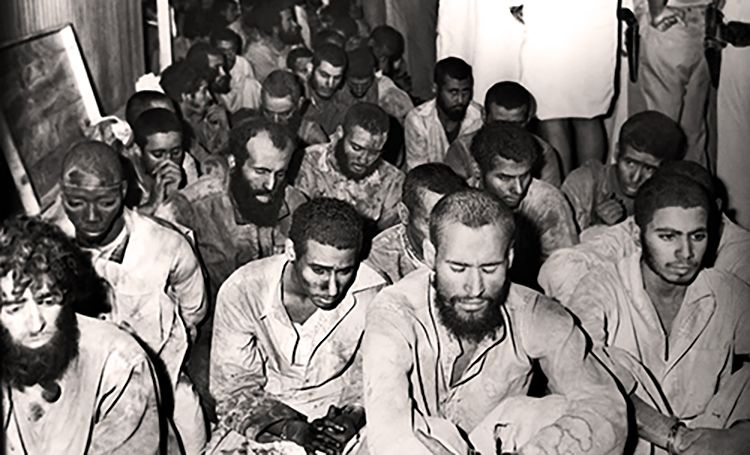

Footage of the captives was broadcast on TV.

Footage of the captives was broadcast on TV.

Their leader, Juhayman, met his end in Makkah on Jan. 9.

Prince Turki recalls meeting the wounded rebel leader in hospital after his capture. “When I came in, he looked up at me and he said, ‘Sir, I’m very regretful for what I did, and please, can you intercede for me with King Khaled, to forgive me?” My answer to him was, ‘You don’t deserve forgiveness, having done what you did,’ and that was the end of it.

“Imagine — after having committed this horrendous crime, not just against us humans, but against God and the holy place of God, and killing so many innocent people.”

A photo of the body of Mohammed Al-Qahtani, the supposed Al-Mahdi.

There was little public sympathy for the plight of the insurgents. Journalist Khaled Almaeena, who was in Makkah for four days of the siege, expressed the general revulsion at what had happened.

“I was horrified that a group of people who looked like a ragtag crowd of bandits could do so much damage,” he recalled.

“When they were captured and the camera swept over them, we wondered what had driven them. What kind of people were they and where had their dangerous ideas come from? Their minds had been corrupted, as well as their ideology ... It was all totally alien to Islam.

“How could they attack and harm people who were worshipping God and then move around the Kaaba itself? It was all something abnormal and beyond imagining.”

So much so, in fact, that the leadership reappraised Saudi Arabia’s embrace of modernization, deciding, as a paper published in the International Journal of Middle East Studies concluded in 2007, that “only a reinforcement of the powers of the religious establishment and its control on Saudi society would prevent such unrest from happening again.”

In 2008 Yaroslav Trofimov, author of the book “The Siege of Makkah,” said that it was clear that “the net losers” of the siege were “the forces of secularism and liberalism within Saudi Arabia.”

“After 1400 (1980), something was broken,” Saudi-born writer Mansour Alnogaidan told Arab News. “What happened? In my opinion, Saudi Arabia lacked the political minds that could support the leadership and explain that the Kingdom could remain as it was: A conservative country that was proud at once to serve the Two Holy Mosques and be open to the world, while being careful of a new seed that could lead to what Juhayman Al-Otaibi’s ideology produced.”

Writer Mansour Alnogaidan speaks about how the siege impacted Saudi Arabia.

Writer Mansour Alnogaidan speaks about how the siege impacted Saudi Arabia.

The sudden clampdown and change, of course, was not lost on the wider world. On Feb. 2, 1980, barely two months after the end of the siege, under the headline “Saudis shy away from westernizing,” The New York Times reported that the seizure of the Grand Mosque had “appeared to unnerve the normally assured Saudi leadership briefly,” and that steps were being taken to appease the Kingdom’s more conservative elements.

“While the extremism of the attackers prevented real public sympathy from developing,” reported the paper, “some of their demands, such as halting soccer, television and the education of women, are not unattractive to fundamentalists who have been upset by infusions of western technology and customs.

“Mindful of the Islamic militancy … in Iran,” the paper added, the government was enforcing “some of the restrictive old laws.”

There had, for example, “been a crackdown on the employment of women” and the publication of photographs of women. A picture of the American actress Bette Davis, claimed the Times, was reported to have been “obliterated in the Arab News.”

Almaeena, a former editor-in-chief of Arab News who was working for Saudi Arabian Airlines at the time, witnessed the siege and had no doubt that it changed the climate in Saudi Arabia. Juhayman, he said, “lost the battle but won the war.”

“At that time Jeddah was a laid-back city,” he recalled. “I used to go to movies with my mother. Women were not told to cover up. In those days you had Saudi singers, women also, and then you had Saudi TV and radio shows, (with) women and men, and things were going on well.”

After the siege, all that changed. “They stopped women from appearing on TV — my wife used to read the news on TV. You could not even get (the famous Lebanese singers) Fairouz or Samira Tewfik to come on TV, and this was a big shock for a country that was used to music.”

Worse was to come. “We should be very frank,” said Almaeena. “The religious police started harassing people, started coming and interfering in our lives, asking questions. It was like the Spanish Inquisition ... a shadow fell over the country.”

Prince Turki said that lessons were certainly learnt by the state. “The first lesson is that you must be wary of any ideas and attempts to change the basic beliefs and tenets of Muslim practice,” he said. “These people adopted a very extreme ideology that came out of imagination and obscure thinking, and did not connect to anything that normal human beings and Muslims in particular have, either in practice or in study or in anything like that.

“And the second thing that we must learn from this is that we must be wary of any attempts to use Islam as a tool for any political activity. Islam as a religion is a code of conduct. It is a system of justice. It is a beneficial core of mercy and bonding between Muslims through the zakat and other issues. As a political system the authority of the ruler, the imam of the community, is supreme, so any khawrij, or ideas, that would go to challenge these core principals of Islam should not be taken lightly.”

Today, Saudi Arabia’s leadership is working to reverse the years of social regression triggered by the siege of the Grand Mosque. “We are returning to what we were before — a country of moderate Islam that is open to all religions and to the world,” Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman told the Future Investment Initiative conference in Riyadh in 2017. “We will not spend the next 30 years of our lives dealing with destructive ideas. We will destroy them today.”

In another interview in 2018, the crown prince acknowledged that for decades after the events of 1979, the form of Islam practiced in Saudi Arabia had been unnecessarily strict and intolerant.

“After 1979, that’s true,” he told the CBS News “60 Minutes” program in his first interview with a US television network, but “this is not the real Saudi Arabia. I would ask your viewers to use their smartphones to find out. Google Saudi Arabia in the 70s and 60s, and they will see the real Saudi Arabia in the pictures.

“We were victims, especially my generation that suffered from this a great deal.”

Before the Iranian Revolution and the siege of Makkah rocked the Muslim world, said the crown prince, “we were living a very normal life like the rest of the Gulf countries.”

“Women were driving cars. There were movie theaters in Saudi Arabia. Women worked everywhere. We were just normal people developing like any other country in the world until the events of 1979.”

Like many Saudis, the journalist Almaeena is grateful to the crown prince for the steps he is taking to modernize Saudi society. “The religious police have been put back in their barracks, and for this I would give him 10 out of 10. They are not out there harassing people. We are living more normal and more relaxed lives.”

In a breathtakingly short time, he said, “things have changed a great deal. Women are more confident and they can go out. Now women drive from Jeddah to Yanbu, and they even drive alone. Women go to gyms.”

Almaeena, who describes himself as a conservative, said that there is “a difference between westernization and modernization. Islam is a modern religion and we want to modernize, not westernize.”

He regrets that his own children “grew up in an environment that was totally alien to me. I learned Islam from my mother who never covered her face.”

It has taken decades for Saudi Arabia to recover its tolerance and respect for personal freedom and now, as the Kingdom moves rapidly back to the future, for all of its citizens the sky is the limit.

For Almaeena, one of the most powerful and inspiring symbols of the new liberalization is the iconic image of the Saudi climber Raha Moharrak, who in 2013 was photographed on the summit of Mount Everest, proudly holding high her nation’s flag.

Moharrak, the youngest Arab and the first Saudi woman to climb the world’s tallest mountain, has said: “I really don’t care about being the first, so long as it inspires someone else to be second.”

Now, 40 years after the events that set back Saudi Arabia’s progress and development by decades, her countrymen and women are finally free once again to reach for their own personal summits.

A letter from the late Prince Sultan bin Abdul Aziz to Brigadier general Faleh Al-Dhahri, thanking him for his service and valor.

A letter from the late Prince Sultan bin Abdul Aziz to Brigadier general Faleh Al-Dhahri, thanking him for his service and valor.

The executed were 41 Saudi citizens, 10 Egyptians, seven Yemenis, three Kuwaitis, a Sudanese and one Iraqi. AFP

Caption

A photo of the body of Mohammed Al-Qahtani, the supposed Al-Mahdi.

A photo of the body of Mohammed Al-Qahtani, the supposed Al-Mahdi.

Prince Turki Al-Faisal recalls his encounter with Juhayman and reflects on the lessons learned from the attack on the Grand Mosque.

Prince Turki Al-Faisal recalls his encounter with Juhayman and reflects on the lessons learned from the attack on the Grand Mosque.

For Saudi National Day this year, Arab News looked at 1979 and how two events – the Iranian Revolution and the attack on the Grand Mosque – set the Kingdom back.

For Saudi National Day this year, Arab News looked at 1979 and how two events – the Iranian Revolution and the attack on the Grand Mosque – set the Kingdom back.

Credits

Writers: Jonathan Gornall, Rawan Radwan, Siraj Wahab

Research: Noor Nugali, Mohammed Al-Kinani, Sarah Sfeir

Editors: Mo Gannon, Tarek Mishkhas

Design: Simon Khalil, Omar Nashashibi

Graphics: Douglas Okasaki, Omar Nashashibi

Photo research: Sheila Mayo

Video editor: Ali Noori

Videographers: Mohammed Alqahwi, Waddah Mudarris, Mohammed Al-Baigan

Photography: Huda Bashatah, Basheer Saleh

Copy editors: Sandra White, Sharif Nashashibi

Social media: Mohammed Qenan

Translation: Jamal Wakim,Joy Geryes, Mohamed Kheir, Anan Tello, Joelle Sleiman, Charbel Merhi, Rua'a Alameri

Sources: .; King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies; American University of Beirut Library; 'The Siege of Mecca" by Yaroslav Trofimov; 'The Siege of Mecca" by Dirk van den Berg (www.mecca1979.com); Asharq Al-Awsat; Al-Riyadh; Assafir; Al-Amal; Al-Riyadh; Al-Jazirah; Okaz; Al-Watan

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas

More Deep Dives