The onset of the global crisis has shortened investors’ investment horizons, stoked preferences for liquid assets and dramatically shifted the regulatory regime in favor of developed market securities, particularly government bonds.

A less documented consequence was that investment banks in developed economies became poorer at making markets in EM securities. In fact, investment banks have been severely dis-intermediated by local EM banking and non-bank financial institutions since 2008/2009.

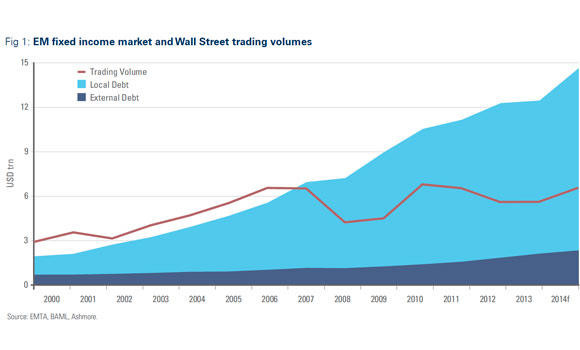

To illustrate the scale of Wall Street’s retreat from EM market-making, we have combined data on EM fixed income trading volumes from the Emerging Market Traders Association (EMTA), a key industry body, with the most comprehensive source of data available on the total size of the EM fixed income universe from BAML. The EMTA data covers mainly Wall Street banks and fund managers in developed economies.

Wall Street banks’ trading in EM fixed income has stagnated around 2007 levels. Wall Street banks today only turn over about 45 percent of EM fixed income in a year compared to more than 100 percent of the asset class per year in 2007.

While no one would question that the best liquidity for Gilts is in London, or that the best place to trade Aussie government bonds is in Australia, many investors still believe they have to go to London or New York to trade EM. This view is outdated. Today the best trading in Peruvian bonds is in Lima; Kuala Lumpur serves up the most liquid trades in Malaysian government bonds; and Sao Paulo is the place to be to trade Brazil local.

In short, EM fixed income market making has gone local. Investors must follow suit. We believe that it is a good thing that EM markets are becoming less beholden to Wall Street’s addiction to short-term momentum trading and the hysteria that accompanies it. Local trading is less risky, because local EM institutional investors today hold the vast majority of local EM bonds. This local liquidity provides a far more reliable ‘buyer of last resort’ backstop than Wall Street banks. Investors should demand that their managers target this local liquidity. “Going local” would also reduce index dependence. Only 15 percent of local bonds are in the most commonly used benchmark index (JP Morgan’s GBI EM GD index), mainly because Wall Street banks tend only to include countries and securities in their indices that they themselves trade (otherwise the banks would incur a cost in collecting pricing data, which they could not recover). Going local therefore means accessing not just greater trading volumes, but also escaping the greater and greater concentrations in index securities in favor of a much wider investment universe.

Middle East

Turning to matters Middle Eastern, the US and the UK have now embarked on a bombing campaign against Islamic State (IS) in Syria and Iraq, accompanied by bombers from several Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. For the US and the UK, which are respectively constrained on the home front by lameduck government and deep regional divisions and parliamentary party defections, a focus on foreign affairs is a welcome distraction. They also go some way to hide the impotence of Western leaders in terms of influencing events in Eastern Ukraine where it is increasingly clear that President Putin is securing a settlement very much to his liking.

Inevitably, the US-led coalition attacks have brought back stereotypes and misconceptions about the Middle East as a region of violence, uncertainty, destabilization and war. Not only are the geopolitical risks arising from IS exaggerated by the media and many analysts, in our view, but more significantly the region is very far from being a single entity under the rubric of the Arab world.

In fact, there is no one Arab World, which is also why there never has been one Arab Street view. The Arab world is as widely different as Europe is from North to South and from East to West. Investors would do well to recognize this differentiation.

For example, the uncertainty and violence of Syria, Iraq and Yemen stand in marked contrast to the situation in GCC states. A commonly held view is that the event in the former could easily spill over to the latter. Similar views prevailed during the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions of the Arab Spring. But such views ignore that Gulf leaders are well-experienced and adept in dealing with radical threats. The Gulf proved to be far more resilient than expected during the Arab Spring, helped in part by a substantial adjustment in social spending. Similarly today GCC countries have recognized the potential risk IS could pose and acted relatively swiftly. The decision to participate in the US-led raids has galvanized support and cohesion within the GCC. In fact, some would argue that through their unified action to support US-led operations, the GCC is more unified than in many years.

No doubt, Syria and Iraq face real challenges to the way their states are organized, and even to their borders, which were invented by French and British colonialists with little regard to the populations living there. Both countries are vulnerable, borderline ungovernable and, as such, their fates as nations are difficult to determine. Even so, despite all the violence in Iraq, for example, there has been no material disruption to Iraqi oil production in the south, because the conflicts that threaten Iraq are in the center and the perennial threat of a breakaway Kurdish state in the north.

The uncertainty about Syria’s future and Iraq’s unity and the more recent developments in Yemen should not lead investors to downplay the economic value and opportunities offered by other countries in the region. During the first week of the attacks there was no significant sell off in regional GCC stock markets. Instead, markets have reflected seasonality and technicals surrounding the annual Haj holiday.

The GCC economies continue to prosper on the back of strong government balance sheets, high public spending and low government debt. Saudi Arabia’s debt to GDP is expected to be less than 2.5 percent by year-end, one of the lowest in the world. Its economy in 2014 is set to grow at 4.5 percent in real terms this year and private sector growth is above 5.5 percent. Saudi Arabia’s foreign exchange reserves are close to 90 percent of its GDP. This means that Saudi Arabia has strong cushions even as oil prices dip below $100 per barrel.

The growth story in the UAE is also gaining momentum. Historically, the UAE has benefited from a perceived safe haven status. Abu Dhabi’s capital investments are growing strongly given a rapid pace of industrialization and provision of infrastructure. Dubai’s ability to position itself as a tourist, logistics and trade hub is noteworthy. Despite instances of exuberance in the property sector, the authorities have taken measures to contain excesses. Qatar, another GCC country, is this year expected to have the fastest growth in the Middle East.

And Kuwait’s economy has benefitted from sustained surpluses over the last few years that offer opportunities for development spending. Kuwait’s unemployment at 3 percent is one of the lowest in the region.

To many, Lebanon and Jordan could be seen as equally vulnerable to an impending crisis. However, Lebanon’s banking system continues to be liquid and stable, despite perennial budgetary shortfalls. Jordan is physically impacted by the crisis in Syria. The continuous inflow of Syrian refugees, low growth and dependence on foreign aid add to the country’s economic burden. Egypt’s worst days have probably passed even if plenty of challenges remain, a budget deficit above 11 percent of GDP being one of them. Nevertheless, Egypt’s equity market has rallied over 40 percent year to date.

In short, generalizations about the Middle East are easy and lazy. In reality, the nuances and intra-regional dynamics are both many and complex. Differentiation requires knowledge and understanding, but is likely to pay off for investors.

— John Sfakianakis is GCC director, Ashmore Group.

GCC economies thriving on back of high public spending, low debt

GCC economies thriving on back of high public spending, low debt