The Coptic miracle

How Egypt's historic Christian church survived and thrived

On Feb. 15 2015, the world reacted with revulsion to the release of a video showing the savage execution of 21 men on a Mediterranean beach, near Sirte in Libya.

Wearing orange jumpsuits, with their hands tied behind their backs, the men were marched to their deaths by the masked, black-clad members of a terror group claiming allegiance to Daesh.

In the video, the camera panned along the line of faces as the leader of the terrorists delivered a rambling speech, condemning the “followers of the hostile Egyptian church.”

Twenty of the men were Egyptians, poor migrant Coptic Christians who had been forced by economic circumstances in rural Upper Egypt to leave their homes and families to seek work in Libya. They had been kidnapped in early January 2015.

The 21st man, a Ghanaian worker who had been captured with them, was a Christian, but not a Copt. Reportedly he was offered his freedom but chose instead to remain with the others, and shared their fate.

All 21 refused to deny their faith. Even as they were forced to their knees, not one of the men struggled, cried out or begged for mercy.

Instead, they remained almost shockingly composed, even as their captors forced them face down onto the sand and pressed knife blades to their throats.

Only then did they break their silence, to offer final, brief prayers in Arabic to Jesus Christ with their last breaths.

One week after the massacre, all 21 would be declared martyrs by Pope Tawadros II, leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.

The Copts, who trace their lineage back to ancient Egypt, and whose religion predates the birth of Islam and its arrival in the land of the Nile, have been a central part of the Egyptian story for two millennia.

Yet for many outside Egypt and the immediate region, the grim video would be their introduction to one of Christianity’s oldest churches, founded in Alexandria by Mark the Evangelist in about A.D. 49.

For the Copts themselves, inured to sacrifice and suffering after centuries of persecution, the horror on the beach was just another chapter in an ancient story that began as it was fated to continue, steeped in the Christian tradition of martyrdom.

A faith forged in martyrdom

Archbishop Angaelos, Coptic Orthodox Archbishop of London, on sacrifice.

Christianity arrived in Egypt early in the first chapters of the Christian story. According to scripture, Mary and Joseph fled to Egypt with the infant Jesus after Herod the Great, King of Judea, ordered the Massacre of the Innocents, the slaying of all male children aged 2 or under in Bethlehem.

An 18th-century French painting depicts the massacre of children in Bethlehem that drove Mary and Joseph to seek sanctuary for the infant Jesus in Egypt. (Getty Images)

During the reign of the Emperor Nero (A.D. 54 to 68), Mark the Evangelist, believed to have been born in the ancient Greek city of Cyrene, near present-day Shahhat in Libya, brought the teachings of Christ to Africa.

There, he founded the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, which would become one of the five episcopal sees, or areas of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, of Christendom, alongside Constantinople, Antioch, Jerusalem and Rome.

The Coptic language, which after centuries of Arabisation survives today in Egypt only in liturgical use in the church, is an evolution of the language spoken in Ancient Egypt. The name “Coptic” is thought to derive from the ancient Greek word for Egypt, Aigyptos, known to the Copts as Kyptos.

The Christian tradition of martyrdom, established so ruthlessly in Rome during the reign of Nero, pursued Mark to Egypt. In A.D. 68, he was martyred when a pagan mob tied a rope around his neck and dragged him through the streets to his death.

Close to 2,000 years separated the martyrdoms of Mark the Evangelist, the founder of the Coptic Church, and the deaths of the 21 in Libya, but each is bound to the other, not only as one of the countless individual threads that make up the tapestry of the Coptic experience, but also through connections that go beyond the commonality of their sacrifices.

After his martyrdom in A.D. 68, St. Mark’s bones remained in Egypt until 828, when at least some were stolen from Alexandria by Venetian merchants, who took the remains on the pretext that they were in danger of being destroyed by the Islamic authorities in the city.

Mark the Evangelist, who founded the Church of Alexandria. His symbol, the lion, just visible in this 17th-century painting, was appropriated by Venice after Venetians stole his bones in 828. (Getty Images)

The theft and subsequent arrival of the relics in Venice, which adopted Mark as its patron saint, is recorded in two 17th-century mosaics on the western facade of the Roman Catholic St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice.

In June 1968, in response to a request by the Coptic Pope Cyril VI on the occasion of the 1,900th anniversary of Mark’s martyrdom, the Roman Catholic Pope Paul VI returned to Egypt what the Vatican described as “part of the Evangelist’s relics.”

Back in Egypt, the arrival of the remains at Cairo airport on June 24, 1968, was greeted by the Coptic Pope, the heads of churches from around the world, and thousands of Egyptians, Christian and Muslim. Two days later, the inauguration of the new cathedral of St. Mark, where the chest containing the relics was laid to rest beneath the main altar, was attended by thousands of Egyptians, among them President Gamal Abdel Nasser.

On Feb. 15, 2018, exactly three years after the beheadings in Libya, a new church was dedicated to the memory of the martyrs in the village of Al-Aour in Minya Province, Upper Egypt, where 15 of the men had lived.

Relatives of the 20 Coptic migrant workers murdered by Daesh in Libya in 2015 pray over their remains at their funeral in 2018 at the Church of the Martyrs in Al-Aour. (Ibrahim Ezzat/AFP)

The construction of the Church of the Martyrs of Faith and Homeland was funded by the Egyptian government — a gesture of inclusive non-sectarianism much appreciated by Egypt’s Copts.

The remains of the men, buried in a mass grave not far from where they had been killed, had not been found until October 2017. In May 2018, the 20 Copts were flown back to Egypt, where they were met at Cairo airport by Pope Tawadros II, and laid to rest in the church dedicated to their memory. The Holy Synod of the Coptic Orthodox Church expressed “sincere thanks” to President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi and his government for their efforts in bringing about the repatriation.

In September 2020, Ghanaian Matthew Ayariga, whose remains had remained unclaimed in Libya, was reunited with his brothers in death at Al-Aour.

An 18th-century French painting depicts the massacre of children in Bethlehem that drove Mary and Joseph to seek sanctuary for the infant Jesus in Egypt. (Getty Images)

An 18th-century French painting depicts the massacre of children in Bethlehem that drove Mary and Joseph to seek sanctuary for the infant Jesus in Egypt. (Getty Images)

Mark the Evangelist, who founded the Church of Alexandria. His symbol, the lion, just visible in this 17th-century painting, was appropriated by Venice after Venetians stole his bones in 828. (Getty Images)

Mark the Evangelist, who founded the Church of Alexandria. His symbol, the lion, just visible in this 17th-century painting, was appropriated by Venice after Venetians stole his bones in 828. (Getty Images)

Relatives of the 20 Coptic migrant workers murdered by Daesh in Libya in 2015 pray over their remains at their funeral in 2018 at the Church of the Martyrs in Al-Aour. (Ibrahim Ezzat/AFP)

Relatives of the 20 Coptic migrant workers murdered by Daesh in Libya in 2015 pray over their remains at their funeral in 2018 at the Church of the Martyrs in Al-Aour. (Ibrahim Ezzat/AFP)

A church apart

At the dawn of Christianity, Alexandria, founded by Alexander the Great in about 332 B.C., was the greatest city of the Near East, a colossus of trade and political power and, as the Egyptian journalist and author Abdel Latif El-Menawy wrote in his 2017 book “The Copts,” “a crossroads of civilization, ... perhaps second only in grandeur to Rome.”

Alexander the Great, who founded and gave his name to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where Christianity would take root some 400 years later. (Getty Images)

The Church of Alexandria soon developed a fraught relationship with Rome, in both secular conflict with the imperial authorities and in spiritual battles with the Roman church. Both took a dim view of this new religion, seemingly beloved of the subversive, the pacifist and the poor.

Christians were most extensively repressed by the Roman empire during the reign of the Emperor Diocletian (A.D. 245-313), in what became known as the Diocletianic Persecution, an empire-wide purge of Christianity that saw Egypt hit particularly hard.

According to one report, between A.D. 303 and 311 more than 600 Christians were killed in Alexandria alone. In 311, in the final throes of the persecution, the Patriarch of Alexandria himself, Peter, was martyred by beheading.

Such was the impact of the persecution that the start of Diocletian’s reign became the year in which the calendar of the Church of Alexandria began.

Even more momentous for the future direction of Christianity in Egypt, however, was the Church’s split from Rome.

The divide began to open in 326, with the election of Athanasius I as the Coptic Bishop of Alexandria. Many of his battles with Rome concerned Arianism, a doctrine which decreed that Jesus Christ was not, in fact, divine, but subservient to God – anathema to the Church of Alexandria, resolutely hostile to any theological position that reduced the divinity of Christ or, worse, suggested separation between Christ and God.

Like the nascent faith of Christianity, the Roman Empire was tearing at its seams, and was finally fully partitioned in 395. Egypt, and Alexandria, fell firmly within the sphere of influence of the Eastern, or Byzantine, Empire, with its grand capital Constantinople.

Heated debates about the nature of Christ finally came to a head in 451 at the Council of Chalcedon. Held near Constantinople, this fourth ecumenical council of the Christian church was called by Marcian, the Roman emperor of the east, to settle the disputes about Christ’s divinity.

The Council of Chalcedon, held near Constantinople in 451, saw the Coptic Church split from the rest of Christendom in a dispute over Christ’s divinity. (Alamy)

Instead, it created a major schism in Christianity that persists to this day. The council concluded that Christ was both divine and human in nature, a ruling that, for the Copts, diluted Christ’s divinity and was heresy.

The council deposed Coptic Pope Dioscorus I, and the bishops who supported him, and the resulting rift saw the Coptic Church leave mainstream Christianity.

The Emperor Theodosius, Marcian’s successor, exiled Dioscorus from Alexandria. The citizens tried to prevent the Emperor’s chosen replacement as Coptic pope from entering the Church of Alexandria, prompting a massacre by Byzantine soldiers.

“Time and again in the early history of the Coptic Church, Egyptian Christians proved willing to protect their churchmen from the watchful eyes of their rulers and, in turn, their Patriarchs sought to protect their congregations from imperial persecution,” wrote El-Menawy.

“The very character of the church was forged in the cycle of oppression and resistance.”

Theological differences with Rome would remain the greatest preoccupation of the Coptic Church of Alexandria until the very eve of seismic events in the seventh century that would reshape the entire region.

In 630, the Roman emperor Heraclius dispatched another emissary to Alexandria to stamp out any remnants of religious separatism. The Coptic Pope, Patriarch Benjamin, was forced to flee to Upper Egypt, seeking sanctuary in one of the monasteries near Thebes.

The Roman Emperor Heraclius, whose reign saw the rise of Islam and the loss of Alexandria to the Rashidun Caliphate. (Alamy)

The internal forced exile of the pope had become something of a pattern which would continue right up to the 20th century.

But the Byzantine hold on Egypt would not last. As Heraclius fretted about disunity among Christians, a powerful new religious force was emerging in Arabia that would soon sweep all before it.

Alexander the Great, who founded and gave his name to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where Christianity would take root some 400 years later. (Getty Images)

Alexander the Great, who founded and gave his name to the Egyptian city of Alexandria, where Christianity would take root some 400 years later. (Getty Images)

The Council of Chalcedon, held near Constantinople in 451, saw the Coptic Church split from the rest of Christendom in a dispute over Christ’s divinity. (Alamy)

The Council of Chalcedon, held near Constantinople in 451, saw the Coptic Church split from the rest of Christendom in a dispute over Christ’s divinity. (Alamy)

The Roman Emperor Heraclius, whose reign saw the rise of Islam and the loss of Alexandria to the Rashidun Caliphate. (Alamy)

The Roman Emperor Heraclius, whose reign saw the rise of Islam and the loss of Alexandria to the Rashidun Caliphate. (Alamy)

The rise of Islam

In 640, one of Islam’s most capable generals, Amr ibn al-As, conquered Alexandria for the Rashidun Caliphate, and the following year the whole of Egypt was surrendered to the Muslims.

The Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, the Muslim general who conquered Alexandria for Islam. Believed to be the first mosque built in Egypt, in 642, it is said to have been raised on the site of the general's campaign tent. (Shutterstock)

Two centuries after their historic split from the Roman church, Egypt’s Coptic Christians now faced a new reality, one that would gradually see the erosion of their numbers, their language and the influence of their faith.

At the time of the Arab conquests, the majority populations in Syria, Egypt and Iraq were Christians, many of whom would convert to Islam in successive waves, even though, as El-Menawy noted, “the initial Islamic conquests were not accompanied by a fanatical urge to convert the world to Islam.”

At first, those who did embrace the new faith “were not compelled to convert, while the remaining Christians, represented by diverse denominations, lived as dhimmis, non-Muslim citizens of an Islamic state, though it was by no means a pejorative term in the early days of the Arab empire.”

Nevertheless, the speed and extent of the Arabisation of the conquered territories in terms of language, religion, government and culture was astounding.

In 706, the Arab governor Abdullah ibn Abdel Malik ordered the use of Arabic as the only language of officialdom. Between the 10th and 13th centuries, the Coptic language, a direct continuation of Ancient Late Egyptian, began to fade out of everyday speech, and Arabic became Egypt’s lingua franca.

Coptic survived only in the services and religious schools of the Church, and retreated to the monasteries, where it survives to this day as a liturgical language, in much the same way as Latin is still used by the Catholic Church.

At first, Copts served the Islamic ruling class as senior administrators, treated in accordance with the Covenant of Omar, the Islamic treaty which laid out the rights and restrictions for non-Muslim Abrahamic religions under Islamic rule.

However, despite these stipulations, Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs mistreated minorities. Kurrah, the governor of Egypt under the Umayyad Caliph, Al-Walid I (705-715), decreed that monks should be branded on their hands with the name of their monastery and the date of their branding, or face having one of their limbs cut off.

Although in the early decades of the Islamic occupation most Egyptians chose to remain Christian, Arab colonists began to settle in the region and, in time, the steady trickle of conversions to Islam became a flood.

By the 10th century, the number of Egyptians conversant in Coptic had become alarmingly small and, to preserve their religion, Coptic bishops had begun to preach in Arabic.

At times, the use of Arabic was enforced. Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, the sixth Fatimid Caliph (996-1020), forbade the speaking of Coptic in public, at home and even inside churches and monasteries. Those caught conversing in the language had their tongues cut out.

The 11th-century Fatimid Caliph, Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, who ordered that anyone who spoke Coptic should have their tongue cut out. (Alamy)

But if there was a single major factor that drove conversion to Islam in Egypt, it was taxation.

The jizya was a divinely ordained tax levied on non-Muslims in any Muslim-ruled land, in lieu of them doing military service and in recompense for their protection by Muslim armies.

Unsurprisingly, as more and more dhimmis began to adopt Islam, a problem arose – revenues dependent upon large pools of tax-paying unbelievers began to dry up.

The answer was more taxes, prompting a series of rebellions in the eighth and ninth centuries until, in 831, a major uprising erupted in the Nile Delta. The Peshmurian Copts in the north held out the longest, but were finally crushed. The survivors were “exiled, imprisoned or enslaved throughout the empire,” wrote El-Menawy, and a turning point in relations between Muslims and Christians had been reached.

“Tired of the revolts, which had by this time become a burden on the empire, the Arabs replaced all the Coptic leaders of Egypt villages and provinces with Muslims, reinforcing Muslim domination of the country.”

Yet, when the Crusaders arrived in the region, 500 years after the initial Arab conquest, the Copts showed no sympathy or willingness to cooperate with their fellow Christians.

Arab rule in Egypt ended in 1250 when the Mamluks, a Muslim warrior class made up originally of slaves from the Caucasus, overthrew the ruling Ayyubid dynasty. Egypt remained in Mamluk hands until 1517, when a new power emerged in Asia Minor. Egypt became an Ottoman province, to be ruled by Turks for the next 300 years.

The Mamluks, a feared dynasty of Muslim warriors, formerly slaves and originally from the Caucasus, controlled Egypt for 300 years before they were succeeded by the Ottomans in 1517. (Getty Images)

It was under the Macedonian-born Ottoman governor, Mohammed Ali, who ruled Egypt virtually as his own kingdom in the first half of the 19th century, that the modern country of Egypt would begin to take shape.

It would do so, however, under the auspices of a new imperial overlord, the largest empire the world had ever seen.

The Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, the Muslim general who conquered Alexandria for Islam. Believed to be the first mosque built in Egypt, in 642, it is said to have been raised on the site of the general's campaign tent. (Shutterstock)

The Mosque of Amr ibn al-As, the Muslim general who conquered Alexandria for Islam. Believed to be the first mosque built in Egypt, in 642, it is said to have been raised on the site of the general's campaign tent. (Shutterstock)

The 11th-century Fatimid Caliph, Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, who ordered that anyone who spoke Coptic should have their tongue cut out. (Alamy)

The 11th-century Fatimid Caliph, Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, who ordered that anyone who spoke Coptic should have their tongue cut out. (Alamy)

The Mamluks, a feared dynasty of Muslim warriors, formerly slaves and originally from the Caucasus, controlled Egypt for 300 years before they were succeeded by the Ottomans in 1517. (Getty Images)

The Mamluks, a feared dynasty of Muslim warriors, formerly slaves and originally from the Caucasus, controlled Egypt for 300 years before they were succeeded by the Ottomans in 1517. (Getty Images)

Divide and rule

By 1882, although nominally an Ottoman province until 1914, Egypt had come fully under the control of the British, whose occupation would last until 1956.

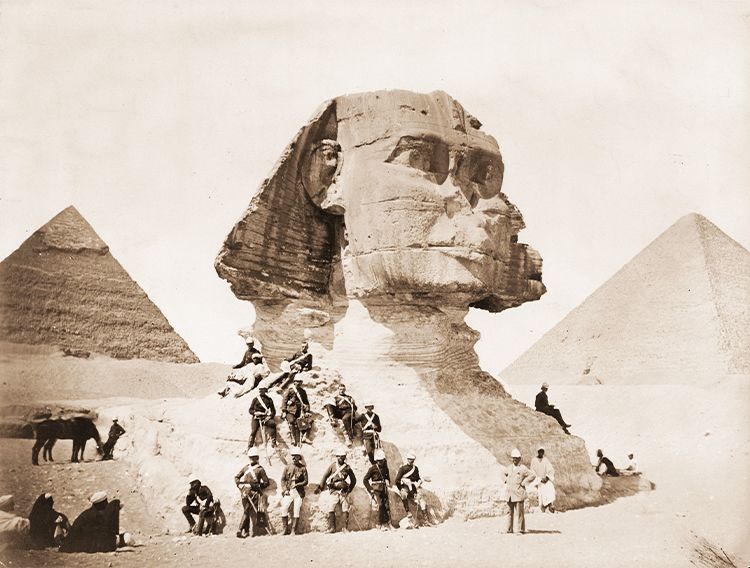

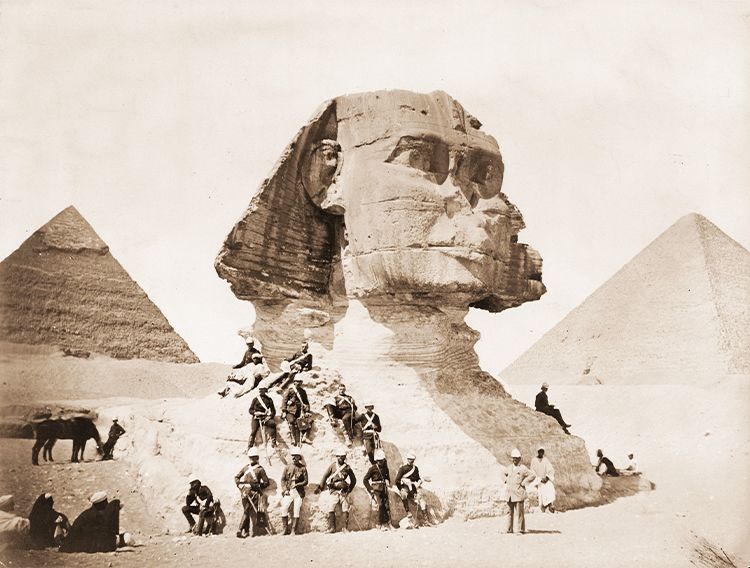

British troops pose by the Great Sphinx of Giza after the bombardment of Alexandria by Royal Navy ships in 1882, which destroyed large parts of the ancient city. (Getty Images)

Historians record the early 19th century in Egypt as a time of harmony between the Copts and the Muslim majority. Examples of this abounded, with the government making grants to Coptic theological schools and, when Copts failed to win seats on local councils, stepping in to appoint some, to ensure Copts were represented.

In 1855, the jizya tax was abolished and under the modernizing Ismail Pasha, the grandson of Muhammad Ali and the Ottoman Khedive (viceroy) of Egypt from 1863 to 1879, Copts were recruited to the advisory Council of Representatives and other arms of Egypt’s bureaucracy.

There were, writes El-Menawy, “numerous examples illustrating the affinity between the two faiths, particularly during religious celebrations. It was often the case that Copts would help build mosques while Muslims helped restore churches.” Muslims and Copts “shared many of the same virtues, qualities, and perspectives on life.”

And yet, “as the 20th century progressed, the two poles of the nation began to pull apart.”

It was no coincidence that the increasing disunity coincided with the period of British rule in Egypt, which began in 1882 and followed the classic colonial strategy of “divide and rule, the deliberate sowing of discontent between Muslims and Copts.”

As a result, “from the beginning of the 20th century, the national movement against the British occupation intensified, while at the same time, an artificial chasm between Muslims and Copts opened up.”

The sham trial and hanging by the British of four Egyptians from the village of Denshawei in 1906 strained relations between Copts and Muslims. In 1909 Coptic prime minister Boutros Ghali, who presided over the trial, was assassinated by a nationalist.

Increasingly, revolutionary forces began to coalesce against the British occupation on nationalist grounds, especially after the First World War, which took a heavy toll on Egypt.

“The impact of the First World War on Egypt was very large,” said Michael Akladios, founder and director of Egypt Migrations, a Coptic cultural and archival project set up in Canada in 2016 to preserve the stories of Egypt’s migrants.

“It brought to light the fragility of British power, and highlighted the need to break the yoke of British control in Egypt.”

Run by the British as a colony in all but name, buildings, goods, animals and citizens were all requisitioned for the war effort. At least 1.5 million Egyptians were conscripted into the Egyptian Labor Corps, enduring horrendous conditions in Palestine and Gallipoli and on the Western Front in France.

After the war, the Egyptians were ready to govern themselves. The British, however, arrested nationalist leaders, sending them into exile, and further provoking the population to riot and unrest.

Finally, in 1919, a revolution erupted, temporarily uniting Muslims and Copts in common cause. Under the leadership of the Muslim minister Saad Zaghloul, the revolutionaries adopted the slogan “Unity of Crescent and Cross.”

Although Copts accounted for only about 10 percent of the population, their aspirations were enmeshed with those of their Muslim fellow countrymen and women. The sheikhs of Al-Azhar called for revolution in the churches, and the priests preached uprising in the mosques.

On Feb. 28, 1922, after years of unrest in every corner of Egyptian society, the British government issued the Unilateral Declaration of Egyptian Independence, recognizing Egypt as an independent sovereign state.

Archbishop Angaelos, Coptic Orthodox Archbishop of London, on hate.

Christians and Muslims were declared equal citizens, but Egyptian independence was conditional. Britain retained its influence in Egyptian public life, kept large numbers of troops in the country and retained control of the all-important Suez Canal.

Worse, said Akladios, as the rise of fascism in Europe during the 1930s began to taint and radicalize politics in Egypt, “the British-controlled monarchy, in order to cement its power in this tense political climate, began to align with the Islamist majority.”

The most obvious product of this was the modification in 1934 of the Ottoman Imperial Reform Edict of 1856, which had introduced widespread reforms across society in a bid to eliminate discrimination against religious and ethnic minorities, including the Copts. The so-called Al-Ezabi Decree rowed back on these reforms, and introduced 10 conditions that had to be met before any application to build a Christian church could be submitted.

“These 10 conditions were really about limiting Copts’ ability in the public sphere, limiting church building, and limiting assignments in political positions and in government posts, and really began the process of marginalizing Copts within Egyptian society,” said Akladios.

Yet the monarchy’s power was further eroded by the rising tide of nationalism during the Second World War. Once again the country was flooded with British troops, and between 1941 and 1943 was transformed into a battlefield in the struggle to defeat Germany’s Afrika Korps.

For many Egyptians, the facade of independence became all too apparent in February 1942 when, at the height of a crisis in the Egyptian government, King Farouk surrendered to British demands, albeit at gunpoint. With Abdeen Palace in Cairo surrounded by troops and tanks, the 10th ruler of Egypt from the Muhammad Ali dynasty agreed to appoint a prime minister chosen by the British.

It was, however, the loss of the 1948 war against the Jews in Palestine that proved the last straw for a group of young Egyptian army officers, who blamed the defeat on Farouk.

By 1952, nationalist and anti-royalist sentiment in Egypt, stoked by years of British occupation and resentment over issues such as the control of the Suez Canal, had reached boiling point.

On July 23, 1952, the so-called Free Officers staged a coup and ousted the king. For the Copts, another dangerous period of change was under way.

Leadership of the new government was quickly assumed by one of the leaders of the coup – Gamal Abdel Nasser, who became president in 1956 with massive popular support, among both Copts and Muslims.

The appointment of Gamal Abdel Nasser as president in 1956 was welcomed by Copts and Muslims alike, but his policies saw the beginning of the Coptic exodus from Egypt. (Getty Images)

Nasser held tremendous sway among the Copts, as illustrated by the praise offered by the late Pope Shenouda III. The president, he said, “was thinking of a nation with no discrimination between Copt and Muslim. He was thinking of the country, not of the sects and religions.”

Yet the policies of the revolution, particularly those of nationalisation and socialism, including land reforms, did little to help the Copts. There was no suggestion that the laws targeted Christians, but they severely hamstrung the Egyptian bourgeoisie, of which the Copts were appreciable constituents.

Even before the revolution, said Akladios, “Copts were being slowly pushed out of Egyptian politics, establishing their own benevolent societies and turning more inward toward the church. Immediately following the revolution, graduate Copts began to emigrate, going to the UK, Canada and the US, because they were hitting ceilings within the schools and professions.”

Yet in 1970, with the sudden end of the Nasser era following the president's untimely death at the age of 52, and the appointment of Anwar Sadat as his successor, Copts were once again plunged into a period of deep uncertainty.

British troops pose by the Great Sphinx of Giza after the bombardment of Alexandria by Royal Navy ships in 1882, which destroyed large parts of the ancient city. (Getty Images)

British troops pose by the Great Sphinx of Giza after the bombardment of Alexandria by Royal Navy ships in 1882, which destroyed large parts of the ancient city. (Getty Images)

The sham trial and hanging by the British of four Egyptians from the village of Denshawei in 1906 strained relations between Copts and Muslims. In 1909 Coptic prime minister Boutros Ghali, who presided over the trial, was assassinated by a nationalist.

The sham trial and hanging by the British of four Egyptians from the village of Denshawei in 1906 strained relations between Copts and Muslims. In 1909 Coptic prime minister Boutros Ghali, who presided over the trial, was assassinated by a nationalist.

The appointment of Gamal Abdel Nasser as president in 1956 was welcomed by Copts and Muslims alike, but his policies saw the beginning of the Coptic exodus from Egypt. (Getty Images)

The appointment of Gamal Abdel Nasser as president in 1956 was welcomed by Copts and Muslims alike, but his policies saw the beginning of the Coptic exodus from Egypt. (Getty Images)

"President of the faithful"

On March 9, 1971, about five months after Nasser’s death, the Coptic church experienced its own seismic shift with the death of Pope Cyril VI and the accession of Pope Shenouda III.

A charismatic leader, Shenouda would make numerous efforts to connect the Coptic church with the global communion, and in 1973 became the first Coptic pope to visit the Pope of Rome since 451.

Back home, however, it quickly became clear that Sadat’s determination to reject Nasserism and secularism would create a hostile atmosphere in Egypt for the Copts. Sadat announced he was “president of the faithful ones” and, to co-opt the Islamists, he emptied the prisons of Salafist prisoners.

“Under Sadat, religion was increasingly replacing nationalism as the foundation of the country,” Samuel Tadros, a research fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Freedom, wrote in his 2013 book, “Motherland Lost: The Egyptian and Coptic Quest for Modernity.”

“Christianity was ridiculed daily in the press. It was only inevitable that this would alienate Copts, who were increasingly fearful for their future. Clashes soon took place. More violence became only a matter of time.”

In 1972, pamphlets distributed across Alexandria falsely accused Shenouda of aggressively proselytising to convert Muslims to Christianity, as part of an alleged plot to make Egypt a Christian nation once again.

Egypt was a tinderbox. All it needed was a spark, which duly arrived in 1972 when an arsonist tried to set fire to a small Christian church in the village of Al-Khanka, a suburb of Cairo. The following Sunday, Coptic protesters massed in Cairo. Led by priests, the crowd marched to Al-Khanka, and held a defiant Mass in protest. Anti-Copt demonstrations erupted, and Coptic houses and shops were burnt to the ground. The government blamed “foreign agitators” for the unrest.

On Oct. 6, 1973, a coalition of Arab states led by Egypt launched a surprise attack on Israel in a bid to recover the Sinai Peninsula and the Golan Heights. Although to this day regarded in Egypt as a victory, the war failed in its main ambition, to return Sinai to Egypt.

Sadat was left with no option but to look to the West, a dramatic change of direction that meant transforming Egypt into a Western market economy, making peace with Israel and suppressing the Islamist currents he had so far encouraged.

Although he would be successful at implanting Egypt firmly within the Western sphere of influence, Sadat failed utterly to constrain the rise of the jihadists, and Islamist resistance began to harden.

Violence against Copts began to escalate. In 1979, arsonists attacked a church in Cairo, and on Jan. 6, 1980, Coptic Christmas Eve, sectarian clashes erupted across the country and several churches were burnt down.

Sadat continued to indulge hard-line Islamists and had few qualms about using Islam to cement his dictatorial powers. When he brought forward a constitutional amendment to allow him to stand for the presidency for more than the two-term limit, he sweetened the proposal with an amendment making the Shariah the basis for all law in Egypt.

The Coptic Pope, Shenouda III, was forced to seek sanctuary in the desert as President Sadat played the Islamist card. (Getty Images)

The Coptic Pope, Shenouda III, was forced to seek sanctuary in the desert as President Sadat played the Islamist card. (Getty Images)

The news terrified the Copts. For some years the government had been making noises about applying the punishment derived from the Shariah for apostasy – the death penalty.

Coptic fears only mounted when, on May 14, 1980, Sadat stood up in Parliament and declared: “I am a Muslim president of an Islamic country.” In an extraordinary speech, wrote Tadros, “he accused the pope of seeking to establish a Christian state in the south of Egypt in Asyut, and accused Copts of aiming to provoke foreign powers against Egypt.”

Relations between Sadat and Shenouda broke down totally.

In March 1981, the pope delivered an angry speech from the pulpit of St. Mark’s, in which he attacked the idea of adopting the Shariah as the basis for laws imposed on non-Muslims.

Three months later, in June 1981, an outbreak of sectarian violence in Cairo’s El-Zawya El-Hamra district left more than 80 Copts dead, and in August three more died in a bomb attack on a church.

The following month, Sadat rescinded the 1971 presidential decree recognizing Shenouda as the Patriarch of Alexandria. The pope was forced into internal exile in the Wadi El-Natrun desert, as many of his predecessors had been since antiquity.

A month later, on Oct. 6, 1981, Sadat was dead, assassinated by a gang of jihadists at a military parade, a victim of the very forces that he himself had unleashed.

A dangerous time to be a Christian

Vice-President Hosni Mubarak, who was wounded during the assassination of Sadat, survived the attack to become Egypt’s fourth president. He introduced a certain degree of political freedom and liberalization of Egyptian politics, and gradually Shenouda was allowed in from the cold.

The presidency of Hosni Mubarak saw Pope Shenouda returned to his rightful position, but Copts would be caught up in the turmoil that followed his overthrow in 2011. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

In January 1983, president and patriarch exchanged messages, wishing each other season’s greetings for the Coptic Christmas, which falls on Jan. 7.

By this time, many politicians, journalists and religious leaders were openly calling for Shenouda’s restoration, and finally, in 1985, Mubarak issued a decree declaring Shenouda III Pope of Alexandria and Patriarch of the St. Mark Episcopate.

But fresh trouble was brewing for the Copts.

Mubarak’s ineffectual state left a vacuum for Islamists to exploit. Although at the outset of his presidency relations between Copts and Muslims were calm, tension was always present, and there was the constant fear that, one day, the frayed bonds between Christian and Muslim would break.

The Muslim Brotherhood's magazine El-Daawa published endless articles against Copts, the gist of which was that they should “be content with their privileged position as dhimmis until, of course, they ultimately saw the light and converted to Islam,” wrote Samuel Tadros.

Instead, the story went, “the Copts were attempting to change the face of Egypt by building more churches than they actually needed. Copts were a fifth column that aimed to subvert the country. Rumors of Copts stockpiling weapons were widespread.”

On New Year’s Day in 2011, a bomb attack on the Two Saints Church in Alexandria left 23 dead and 97 injured.

Mourners at the funeral of Pope Shenouda III on March 20, 2012. More than a million passed by his body in St Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

There were many causes behind the general revolution that erupted in Egypt on Jan. 25, 2011, but the sense of anger among Copts at the government that followed the bombing quickly escalated into general protests involving both Christians and Muslims.

By Feb. 11, Mubarak was gone and “many Copts were deeply uncertain as to what the future would bring,” wrote El-Menawy. “The general breakdown in law and order that accompanied the fall of Mubarak was certainly not conducive to their safety.”

It was, he added, “a dangerous time to be a Christian in Egypt.”

It was also a sad time. On March 17, 2012, with Egypt’s future still in the balance, Pope Shenouda, whose papacy had been so entwined with the Mubarak presidency, died at the age of 88.

Coptic Pope Tawadros II on the true motive behind attacks on Copts.

Shenouda’s death provoked a wave of grief. More than a million people came to pay their respects in St. Mark’s Cathedral in Cairo, where his unshrouded body sat in state. Messages of condolence were sent by Pope Benedict XVI and US President Barack Obama, and in Egypt tributes were paid by every major political faction, from the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces to the Muslim Brotherhood.

In October 2012, a small boy, blindfolded, stood in front of a packed congregation in St. Mark’s Cathedral. After much prayer and singing of hymns, the boy had his hand placed in a glass chalice, and pulled out a paper ribbon. Written on it was the new pontiff’s name, Tawadros, and the whole cathedral erupted in applause and cheers.

“Tawadros is the 118th leader of the church,” announced Anba Pachomios, the acting pope. “Many blessings and congratulations to you.”

Mohamed Mokhtar Gomaa, dean of the faculty of Islamic and Arabic studies at Al-Azhar University and Egypt’s future Minister of Religious Endowments, congratulates Tawadros II after his enthronement as Coptic Pope in Saint Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo, on Nov. 18, 2012. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

In much the same way had the Coptic pope been selected for centuries.

The presidency of Hosni Mubarak saw Pope Shenouda returned to his rightful position, but Copts would be caught up in the turmoil that followed his overthrow in 2011. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

The presidency of Hosni Mubarak saw Pope Shenouda returned to his rightful position, but Copts would be caught up in the turmoil that followed his overthrow in 2011. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

Mourners at the funeral of Pope Shenouda III on March 20, 2012. More than a million passed by his body in St Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

Mourners at the funeral of Pope Shenouda III on March 20, 2012. More than a million passed by his body in St Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

Mohamed Mokhtar Gomaa, dean of the faculty of Islamic and Arabic studies at Al-Azhar University and Egypt’s future Minister of Religious Endowments, congratulates Tawadros II after his enthronement as Coptic Pope in Saint Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo, on Nov. 18, 2012. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

Mohamed Mokhtar Gomaa, dean of the faculty of Islamic and Arabic studies at Al-Azhar University and Egypt’s future Minister of Religious Endowments, congratulates Tawadros II after his enthronement as Coptic Pope in Saint Mark’s Cathedral, Cairo, on Nov. 18, 2012. (Khaled Desouki/AFP)

Dark before the dawn

In June 2012, following a period of rule by an interim military government, Mohammed Morsi was elected president of Egypt, only to be deposed by a military coup in July 2013, in the wake of mass protests at his Islamist agenda.

In 2014, when coup leader Gen. Abdel Fattah El-Sisi was elected president with 97 percent of the vote, Pope Tawadros II sent him a congratulatory message. His election, said the pope, was “an expression of a pure popular will, and the church prays to God to provide you with assistance in overcoming the challenges facing the homeland, to realize the hopes and aspirations of all Egyptians.”

Both pope and president assumed leadership at a time of sudden change, and both believed passionately in interfaith dialogue. El-Sisi would go on to be the first president to attend a Coptic Mass in Egypt, speaking at a Christmas service and wishing the congregation a merry Christmas.

But the threat of violence continued to haunt Tawadros and the Copts.

In the wave of Islamist anger that followed the toppling of Morsi, Christians were targeted with vandalism and violence. In August 2013, no fewer than 43 churches were completely destroyed and 207 other properties attacked.

Then, in February 2015, came the horror on the beach in Libya. So hideous was the crime that El-Sisi visited the Coptic cathedral in Cairo to offer his condolences, condemning the “heinous act of terrorism” and declaring seven days of national mourning.

The day after the beheadings, the president dispatched Egyptian Air Force F-16 jets to exact vengeance in a series of raids on Daesh targets in Libya.

In 2017, St. Peter and St. Paul’s church in Cairo was bombed, killing 29. Months later, on Palm Sunday in April, Pope Tawadros himself was targeted in a Daesh bombing of two Coptic churches. One bomb struck a church in Tanta, the other St. Mark’s Cathedral in Alexandria. Tawadros was unharmed, but 45 people were killed and 126 injured.

In a clip from the shocking video released by Daesh on Feb. 15, 2015, the 20 migrant Coptic workers captured in Libya are led to their deaths on a beach near Tripoli.

The following May, 28 Copts were killed and 25 wounded when a busload of pilgrims travelling to the Monastery of St. Samuel the Confessor, 135 kilometers south of Cairo, was attacked by gunmen. Children were among the victims.

The year ended with the deaths of 11 people in an attack on a church in Helwan.

Over the past decade, Egypt has been consistently among the top three or four countries with the most entrants in the US Green Card lottery scheme, known officially as the Diversity Visa Program, designed to attract a diverse range of immigrants to America.

Fadi Mikhail, a British-born Coptic iconographer whose art bridges cultures.

It is not possible to identify the number of Copts among the Egyptian entrants to the lottery. But after the series of attacks in 2017, the number of Egyptians seeking a Green Card rose sharply, surpassing 1 million for the first time in 2018, and climbing to 1.39 million in 2019 and a record 1.42 million the following year.

Today, Egyptians remain at the head of the line for Green Cards. In 2021, 11.8 million people around the world were vying for the 50,000 visas on offer. The largest number from a single country – 872,505 – came from Egypt, and in the event the largest number of Green Cards issued that year – 6,002 – went to Egyptians.

Yet while each series of events such as those in 2017 has prompted some Copts to leave Egypt, fear of persecution has never been the only motivation for Coptic emigration, according to anthropologist Candace Lukasik, assistant professor in philosophy and religion at Mississippi State University and the 2019-2020 inaugural research fellow in Coptic Orthodox Studies at Fordham University.

“Emigration ebbs and flows,” said Lukasik. “After 2011 it increased, and again in 2013 and 2017. Yes, the Copts who leave Egypt are leaving because of the uncertainty of where the country is going, but also because they want a better life.”

Today, there are an estimated 15 million Copts in Egypt, about 10 percent of the country’s population, but as many as 2 million now live abroad, chiefly in the US, Canada, Australia and Europe.

Wherever they have put down roots, Coptic communities have flourished, and Egyptian-born Coptic Christians have achieved global success and fame in many fields.

High-profile Copts include heart surgeon Magdi Yacoub, who was born into a Coptic family in Bilbeis, Egypt, in 1935 and after graduating from Cairo University moved to Britain to pursue a career as a cardiothoracic surgeon and became world famous for pioneering techniques in heart valve repair and heart transplants.

Egyptian politician and diplomat Boutros Boutros-Ghali was born into a Coptic Christian family in Cairo in 1922. The grandson of Boutros Ghali, prime minister of Egypt until his assassination in 1910, he served as Egypt’s foreign minister from 1977 to 1991 and from 1992 to 1996 he was Secretary-General of the United Nations.

After Boutros-Ghali died in a Cairo hospital in 2016, aged 93, the prayers at his funeral were led by the Coptic pope, Tawadros II.

Another Copt who needs no introduction in the West – although his Coptic origins are not widely known – is Hollywood actor Rami Malek, star of films including the most recent Bond movie, No Time To Die. Born in California, he is the son of Coptic Orthodox parents who migrated from Cairo to the U.S. in the 1970.

Many Copts have made their mark around the world, among them the Hollywood actor Rami Malek, born in California the son of Coptic Orthodox parents who migrated from Cairo to the U.S. in the 1970s. (AFP)

The first Coptic parish in North America, St. Mark’s, was established in Toronto in 1964. It was followed shortly afterwards by the parish of St. Mark’s in New Jersey, which was founded in the late 1960s and saw the building of the first Coptic church in the West.

There are now at least 197 Coptic churches in the US, scattered across 40 states, and 27 in Canada.

One of the oldest Coptic communities in the West was founded in the 1950s in the UK, where the first Coptic liturgy in Europe was conducted in London on Aug. 10, 1954.

In 1978, Pope Shenouda III travelled from Egypt to the UK to consecrate St. Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Church in Kensington, London, the first Coptic Orthodox church in Europe.

Since then, the church in the UK has gone from strength, with in excess of 20,000 faithful across 32 parishes.

The foundation stone for the Cathedral of St. George in the Hertfordshire town of Stevenage, which was inaugurated in 2006, was laid by Pope Shenouda III on Aug. 18, 2002.

The dazzling icons that adorn the cathedral were painted by Fadi Mikhail. Born in England, the son of Coptic parents who emigrated from Egypt in the Seventies, so his father could better pursue his career as a doctor, Mikhail's art bridges two cultures.

Coptic icons painted by British-born Copt Fadi Mikhail, whose parents emigrated in the 1970s, can be seen in churches in Egypt and abroad.

He studied in Los Angeles under the renowned Egyptian iconographer Isaac Fanous before graduating from the Slade School of Fine Art in London. Today he produces icons for Coptic churches around the world and has a parallel career as a successful artist in the western style, with his work showcased in British galleries.

Although many Coptic communities around the world consist largely of professionals – in the UK, for example, many Copts are medical doctors who came to further careers that hit glass ceilings in Egypt – the US Green Card lottery program has attracted applicants from poorer, working-class Copts.

Because of this, said Lukasik, “I would argue that the Coptic community in the US is more economically diverse than many other Coptic communities around the world.

“Over the past 10 years more and more Copts have applied for the Green Card lottery, and maybe they don’t even do it themselves. There are many communities that I've spoken with (in Upper Egypt) with stories of churches entering their entire congregation into the lottery.”

Michael Akladios agrees that it is a mistake to characterise all Coptic emigration from Egypt as the product of fear or persecution. His family emigrated to Canada when he was 8, joining his father’s siblings who had already settled in Toronto, and the move was “economically motivated.”

“People move all over the world, and it’s always been the same for young professional Copts, too,” he said.

In the 1950s, an earlier generation “did their Ph.D.s in the UK, or in Switzerland, or even in the Soviet Union and the Czech Republic in the 1960s, and then ended up maybe going back to Egypt for a while before emigrating permanently to New York or Toronto. The movement has always been complicated and largely economically motivated,” Akladios said.

“Yes, persecution is an element. But I think we need to realize that the Copts are more than their churches; they're also human beings with needs and families and support systems and networks, and they make decisions as pragmatic migrants just like anybody else.”

In a clip from the shocking video released by Daesh on Feb. 15, 2015, the 20 migrant Coptic workers captured in Libya are led to their deaths on a beach near Tripoli.

In a clip from the shocking video released by Daesh on Feb. 15, 2015, the 20 migrant Coptic workers captured in Libya are led to their deaths on a beach near Tripoli.

Many Copts have made their mark around the world, among them the Hollywood actor Rami Malek, born in California the son of Coptic Orthodox parents who migrated from Cairo to the U.S. in the 1970s. (AFP)

Many Copts have made their mark around the world, among them the Hollywood actor Rami Malek, born in California the son of Coptic Orthodox parents who migrated from Cairo to the U.S. in the 1970s. (AFP)

Coptic icons painted by British-born Copt Fadi Mikhail, whose parents emigrated in the 1970s, can be seen in churches in Egypt and abroad.

Coptic icons painted by British-born Copt Fadi Mikhail, whose parents emigrated in the 1970s, can be seen in churches in Egypt and abroad.

A new republic?

Regardless of the problems they have faced, wrote El-Menawy, “many Copts see no home for themselves (other) than Egypt and will remain there, as will their children, and their descendants for centuries to come.”

He concluded: “Whatever the future brings for the Coptic Church, the Copts will remain a vibrant and integral tributary to Christianity in the world today, just as they are an essential fact of the culture, the history and the nation of Egypt.”

Archbishop Angaelos, Coptic Orthodox Archbishop of London, on forgiveness.

Eight years into the presidency of El-Sisi, that appears increasingly to be the position adopted by the Egyptian state and, encouraged by messages and acts of interfaith inclusivity from the top, there have been significant expressions of ecumenical fellowship.

In January 2021, Egypt’s Grand Mufti Shawki Allam issued a fatwa permitting Muslims to work as paid laborers in the construction of Christian churches.

The following month the Coptic archdiocese of Qena contributed funds toward the completion of Al-Nuamani Mosque in Deshna, which was being built adjacent to the St. George Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in the city.

Then, on Jan. 6, 2022, President El-Sisi joined Pope Tawadros for Christmas Mass in the Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ in Egypt’s New Administrative Capital. In a short speech, the president spoke of a “new republic” in Egypt, “that accommodates everyone without discrimination.”

Under the leadership of Pope Tawadros II, seen here with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman during his visit to St Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Cairo in March 2018, the Coptic church has forged friendships with leaders of all faiths.

This republic, he added, would be based on “dreams, hopes, science and hard work,” and would be “built by all Egyptians.”

Just over a month later, Copts celebrated what may yet prove to be a pivotal moment when the first Coptic Christian was sworn in as head of Egypt’s Supreme Constitutional Court, the highest judicial authority in the country.

Egypt’s National Council for Human Rights greeted the announcement of the appointment of Judge Boulos Fahmy Eskandar on Feb. 9, 2022, as a “historic giant step in the field of civil and political rights to assure that each Egyptian is afforded their full rights without any discrimination.”

During a visit to the Vatican in April 2017, Pope Tawadros II signed a joint declaration with Pope Francis, pledging to “strive for serenity and concord through a peaceful co-existence of Christians and Muslims.” (AFP)

For Michael Akladios, the appointment by El-Sisi of a Copt as the 19th judge to preside over the court since it was established in 1969 was “a promising step on the road to greater Coptic inclusion and representation in Egypt's public sphere.”

Although it was “still too early to judge what ramifications this appointment will have for Coptic communities in Egypt and across its diasporas,” the appointment was nevertheless “symbolic of the state's continued big gestures for cementing national unity as a prevailing feature of the character of the nation.

“In my community, the news was met with much gladness.”

Copts around the world are watching events in Egypt with cautious optimism. Among them is Archbishop Angaelos, the head of the church in the UK.

Pope Tawadros and Bishop Angaelos of the Coptic church in Britain meet Queen Elizabeth II during a private audience at Windsor Castle in May 2017. (Getty Images)

Born in Cairo in 1967, Angaelos emigrated as a child with his family to Australia. There, he obtained a degree in political science, philosophy and sociology and, after postgraduate studies in law, in 1990 returned to Egypt, where he became a monk and joined the historic monastery of St. Bishoy in Wadi El-Natrun.

He served as papal secretary to Pope Shenouda, his “spiritual father,” until 1995, when he was sent to the UK as a parish priest. In 1999, he was made a general bishop of the Coptic Orthodox Church and on Nov. 18, 2017 was enthroned as the first Coptic Orthodox Archbishop of London.

There are, Angaelos said, “still challenges” for followers of the faith. “But one of the most important things for Copts today, in Egypt and abroad, is that over the past decade we have seen a much greater, harmonious existence between Christians and Muslims.”

Copts, he said, have welcomed the gestures of fellowship from the Egyptian government, such as El-Sisi joining the pope for Christmas Mass in the Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ in January.

“Gestures are nice,” he said. “But gestures are not the things that reassure people. What has reassured them more is the actions they have seen. For example, for decades we were obliged to build churches illegally in Egypt, and now there is a move to legalize and legitimize all of these places of worship.

“We have seen a greater openness to engagement with the church; we have seen the President and the upper echelons of the government making efforts to do things differently, and they have had their fruits.”

Ultimately, Angaelos believes, the acceptance of Copts as equal partners in El-Sisi’s “new republic built by all Egyptians” will bear fruit for all of Egypt.

“There is a well-known hypothesis that a nation with freedoms and respect for all its people is a successful nation, because it draws on the gifts and the abilities of all its people, not just a section of them,” he said.

“So the more Egypt becomes all-encompassing and all-embracing, holding everyone equally accountable, but also protecting everyone equally, the more we will see a thriving nation. And everyone will benefit from that.”

Under the leadership of Pope Tawadros II, seen here with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman during his visit to St Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Cairo in March 2018, the Coptic church has forged friendships with leaders of all faiths.

Under the leadership of Pope Tawadros II, seen here with Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman during his visit to St Mark’s Coptic Orthodox Cathedral in Cairo in March 2018, the Coptic church has forged friendships with leaders of all faiths.

During a visit to the Vatican in April 2017, Pope Tawadros II signed a joint declaration with Pope Francis, pledging to “strive for serenity and concord through a peaceful co-existence of Christians and Muslims.” (AFP)

During a visit to the Vatican in April 2017, Pope Tawadros II signed a joint declaration with Pope Francis, pledging to “strive for serenity and concord through a peaceful co-existence of Christians and Muslims.” (AFP)

Pope Tawadros and Bishop Angaelos of the Coptic church in Britain meet Queen Elizabeth II during a private audience at Windsor Castle in May 2017. (Getty Images)

Pope Tawadros and Bishop Angaelos of the Coptic church in Britain meet Queen Elizabeth II during a private audience at Windsor Castle in May 2017. (Getty Images)

Credits

Writer: Jonathan Gornall

Research: Alex Webster, Leen Fouad

Editor: Tarek Ali Ahmad

Creative director: Simon Khalil

Designer: Omar Nashashibi

Graphics: Douglas Okasaki

Video producer: Mohammed Qenan

Video editor: Hasenin Fadhel, Abdulrahman Fahad bin Shulhub

Picture researcher: Sheila Mayo

Copy editor: Les Webb

French editor: Zeina Zbibo

Social media: Jad Bitar, Daniel Fountain

Producer: Arkan Aladnani

Editor-in-Chief: Faisal J. Abbas