Saudi Arabia's

heritage treasures

The five historic sites inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List tell a story of universal importance

One of the objectives of the increasingly outward-looking nation of Saudi Arabia, set out in the ambitious Vision 2030 document and its plan to create a more diverse and sustainable economy, is to open up the Kingdom to visitors as a destination for heritage tourism.

Among the attractions long closed off to much of the world are many hundreds of historic sites.

Some date back to prehistory and comprise key chapters in the story of humankind’s evolution and migration out of Africa. The twin rock art complexes of the Hail region, parts of which are 10,000 years old, are “among the most fascinating and largest rock art sites of the world.”

Others provide mute evidence of the transformation of the Arabian Peninsula over millennia from a lush haven of greenery, lakes and rivers to a largely arid landscape.

Even as the world is facing accelerating climate change on a scale never witnessed before, these sites tell the extraordinary and timely story of how human beings have adapted to changing circumstances with determination and ingenuity.

Some of these sites were known to ancient Greek and Roman historians or to travelers in the 18th and 19th centuries. Others have been studied extensively by modern scholars and archaeologists from Saudi Arabia and around the world.

Very few, however, have been visited by tourists, and some are unknown even to Saudi citizens.

Now, all that is set to change, with a plan to make Saudi Arabia a major global destination, welcoming 100 million international and domestic visitors by 2030.

Part of that plan is to increase the number of visitable heritage destinations in the country from 241 to 447. Five of those sites, which have been recognized by UNESCO as being of “outstanding universal value,” are the jewels in the crown of Saudi Arabia’s past.

Inspired by a successful international effort to save numerous sites and monuments in the Nile Valley, threatened by Egypt’s plans to build the Aswan High Dam, UNESCO adopted the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World’s Cultural and Natural Heritage at its 17th session in Paris in 1972.

Saudi Arabia was one of the first state parties to adopt the convention, which it did in August 1978. Over the next decades, many sites in the Kingdom were identified and protected, and in January 2007, Saudi Arabia nominated its first site for inscription on the World Heritage List — Hegra, the rock-carved city of the Nabataeans.

Saudi Arabia was one of the first state parties to adopt the convention, which it did in August 1978. Over the next decades, many sites in the Kingdom were identified and protected, and in January 2007, Saudi Arabia nominated its first site for inscription on the World Heritage List — Hegra, the rock-carved city of the Nabataeans.

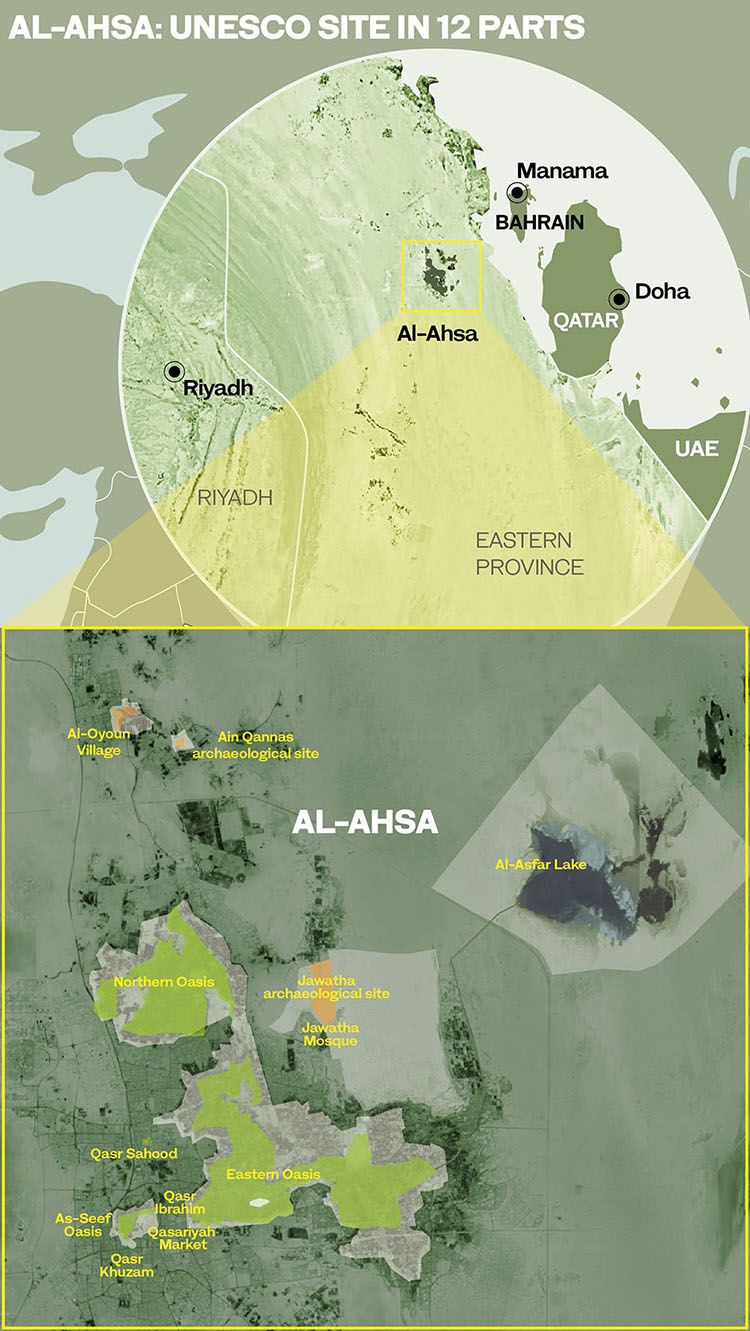

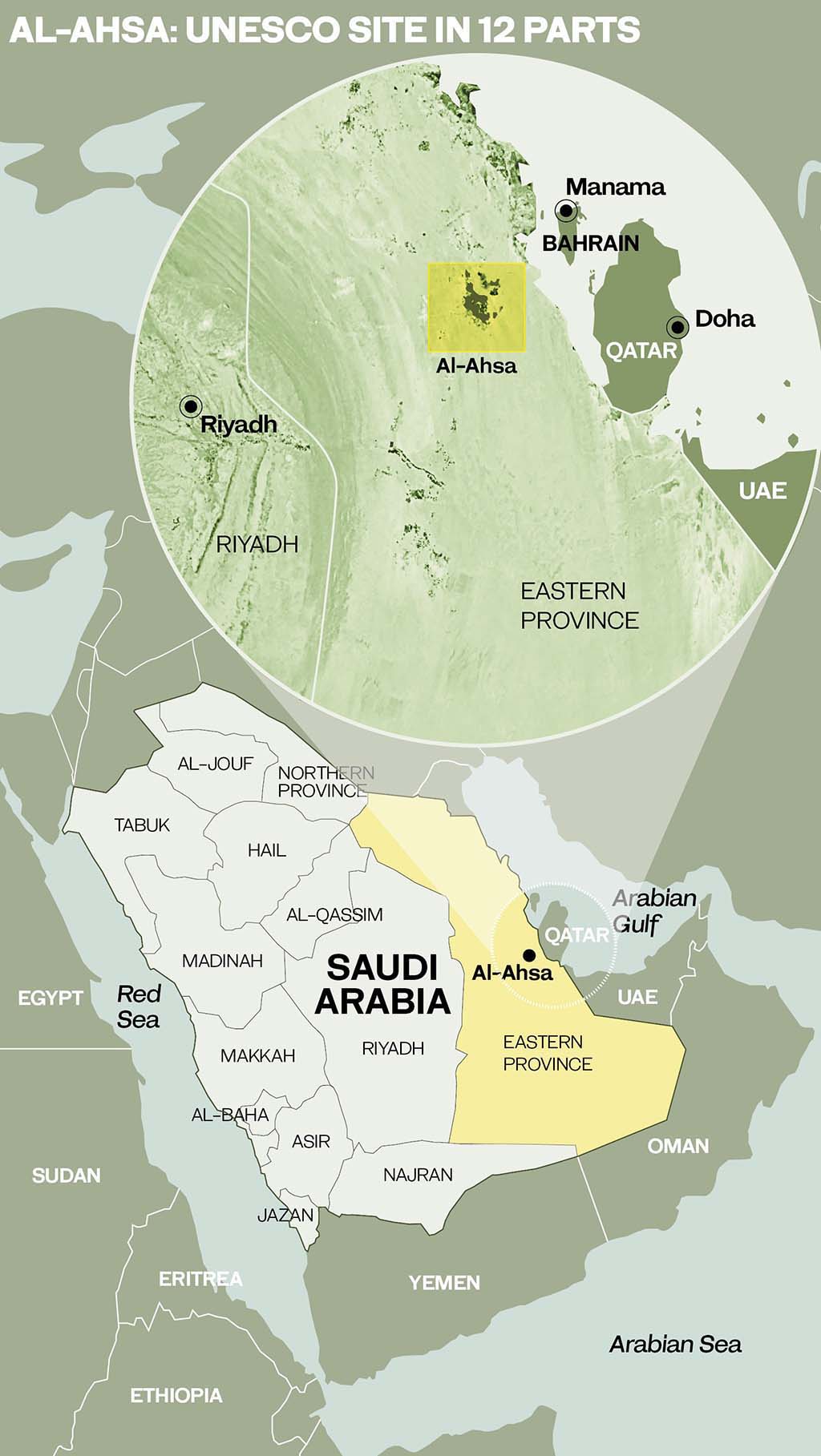

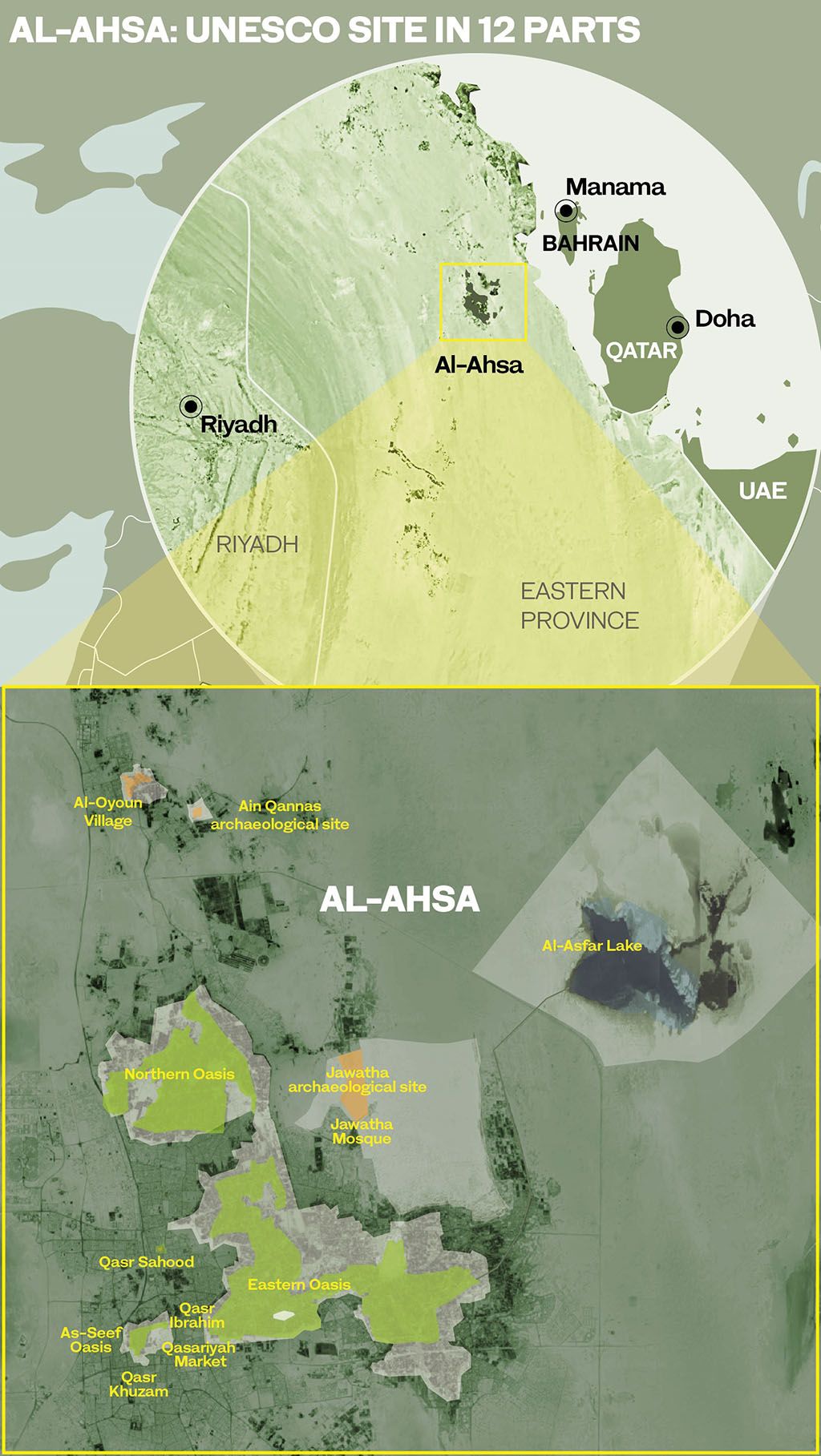

Four other sites have subsequently been adopted by UNESCO — the most recent was Al-Ahsa, the world’s oldest and largest oasis, listed in 2018 — and work is now under way on nominating more sites.

The stories of how the Prophet Muhammad received and spread the word of God in the seventh century, and of how King Abdul Aziz Al-Saud, known as Ibn Saud, forged a nation from a multitude of disparate and warring tribes in the early 20th century, are as familiar as they are epic.

Less familiar, however, is the story of the deeper foundations of the region, upon which the modern state of Saudi Arabia was built and whose origins date back 10,000 years or more.

Together, Saudi Arabia’s five UNESCO sites tell that story — from the wonders of the world’s largest collection of prehistoric petroglyphs, the mysterious rock-carved tombs of the ancient Nabataean city of Hegra and the world’s largest and oldest oasis, to the mud-brick settlement that is the birthplace of the modern Saudi state and the unique houses of old Jeddah, for centuries the gateway to the holy city of Makkah.

Hail: Rock art

Messages from an ancient past

On March 2, 1972, NASA’s Pioneer 10 probe blasted off from Cape Canaveral, bound for a brief rendezvous with the planet Jupiter and a one-way voyage to the edge of the solar system and the infinity beyond.

On board was a simple aluminum plaque, measuring just 22 by 15 centimeters. Created by the cosmologist Carl Sagan, it bore a series of simple pictorial messages designed to convey basic details about the nature and location in the universe of human life to any intelligent extraterrestrial being that might one day encounter the probe.

In both its design and intent, there is a striking similarity between the plaque and the designs carved by ancient peoples into the rocks of Saudi Arabia’s Hail region, a stunning collection of thousands of petroglyphs that together tell the story of almost 10,000 years of human history.

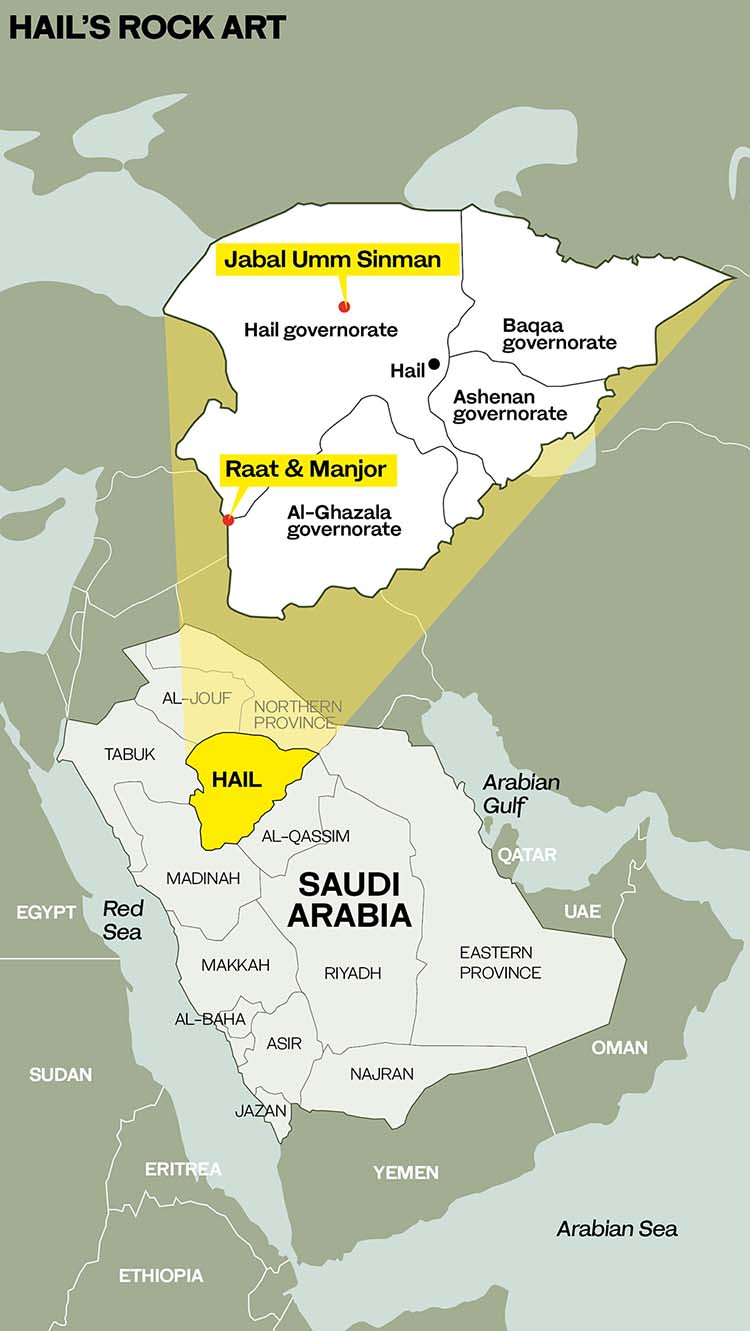

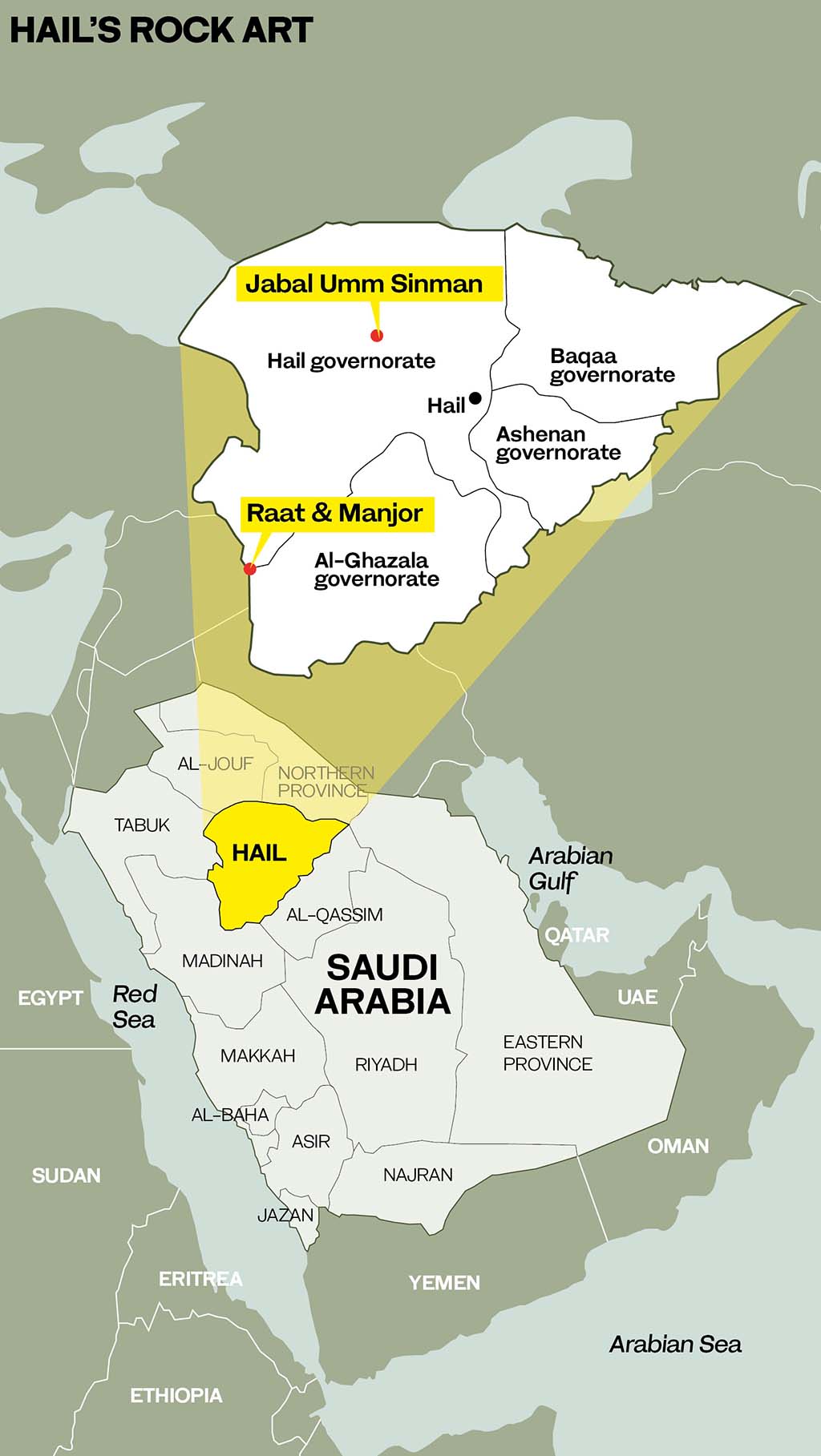

Adopted by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site of “outstanding universal value” in 2015, the world’s largest and most impressive collections of Neolithic petroglyphs, or rock carvings, can be found at two sites some 300 kilometers apart in the Hail province of Saudi Arabia.

The first is at Jabal Umm Sinman, a rocky outcrop to the west of the largely agricultural modern town of Jubbah, some 90 kilometers northwest of the city of Hail and 680 kilometers from the capital Riyadh. The town’s origins as an oasis date back to the dawn of Arab civilization, when the hills of Umm Sinman overlooked a freshwater lake, eventually lost beneath the sands of the surrounding Nefud desert some 6,000 years ago.

It was on these hills, in the words of the UNESCO nomination document, that the ancestors of today’s Saudi Arabians “left the marks of their presence, their religions, social, cultural, intellectual and philosophical perspectives of their beliefs about life and death, metaphysical and cosmological ideologies.”

The second site, which remarkably was discovered only 20 years ago, is at Jabal Al-Manjor and Jabal Raat, 220 kilometers southwest of Jubbah and near the village of Shuwaymis.

Many rocks, such as this one near Shuwaymis, carry images of the bezoar, a wild goat that is rare in Arabia today but was once common across the peninsula. (Saudi Tourism)

Jubbah, with 14 clusters of petroglyphs, was already regarded as the most significant site in the Arabian Peninsula. The discovery of the neighboring site near Shuwaymis, with a further 18 clusters, compounded the Hail region’s claim to possessing one of the world’s most significant collections of rock art, “visually stunning expressions of the human creative genius by world standards, comparable to the messages left by doomed civilizations in Mesoamerica or on Easter Island … of highest outstanding universal value.”

Together, the twin sites tell the story of over 9,000 years of human history, from the earliest pictorial records of hunting to the development of writing, religion and the domestication of animals including cattle, horses and camels.

As the UNESCO documents record, these sites justify their inscription on the World Heritage List not only because of their “spectacular environmental setting in the midst of a desert,” but also because they feature “large numbers of petroglyphs of exceptional quality attributed to between 6,000 and 9,000 years of human history, followed in the last 3,000 years by very early development of writing that reflects the Bedouin culture, ending in Quranic verses.”

Furthermore, the Jubbah and Shuwaymis sites comprise, among numerous other rock art and archaeological features, “the world’s largest and most magnificent surviving corpus of Neolithic petroglyphs.”

Neolithic rock art is found at many locations across Eurasia and North Africa, “but nowhere in such dense concentration or with such consistently high visual quality.”

Created in an age before writing and painstakingly pecked, chiseled and engraved out of the sandstone rocks of the region, the rock art is a simple but vivid record of human existence that, like Sagan’s plaque meant for aliens, conveys the basic details of life on Earth at a moment in time.

Dr. Majid Khan, who, as one of the world’s leading experts on the rock art of Saudi Arabia, played a major role in the nomination of the twin sites for recognition by UNESCO, said the petroglyphs are as good as a written diary of humankind’s adaptation to the challenges of survival in an environment that changed dramatically over thousands of years.

“The rock art of Jubbah represents all phases of human presence from the Neolithic period — 10,000 years before the present time — until the recent past,” said Khan, who has published numerous books and papers on the subject and is a consultant to the antiquities department of the Saudi Ministry of Culture.

“The types of animals depicted suggest change in climate and environment. Large ox figures, for example, indicate a cool and humid climate, while the absence of ox figures and the appearance of camel petroglyphs represent hot and dry conditions.”

Over millennia, the heart of Arabia was transformed from a savannah-like wetland, through which lions roamed and rivers ran, until by about 3,000 B.C. it had become the arid desert landscape familiar today, in which wadis, wells and precious, scattered oases became the keys to life.

The forebears of today’s Arabs clung on stubbornly to existence as the climate and the landscape changed around them. The astonishing petroglyphs that can be seen at Jubbah and Shuwaymis tell a story of human determination, ingenuity and adaptation in the face of a slow-moving but ultimately inexorable environmental disaster.

As the nomination document submitted to UNESCO by Saudi Arabia makes clear, the triumph of these early Arabs against near-impossible odds carries a special message of hope today for a world facing the looming prospect of climate change.

“The cultures that were responsible for the petroglyphs have adapted to changing climate and severely fluctuating water availability,” reads the UNESCO citation.

“As a library recording the interaction of successive societies with their volatile environment, subjected to desertification, lowering of aquifer, volcanic eruptions and the irreversible changes that characterize Arabia today, the rock art provides a unique testament.”

The art, “an exceptional record of human interaction with a deteriorating environment,” is nothing less than “a comprehensive demonstration of … resilience and determination in the face of catastrophic changes.”

At both Jubbah and Shuwaymis, the presence of the human beings who so dramatically left their mark on the world they left behind can be felt not only through their art but also through the crude tools discarded at the sites — hammer stones fashioned by, and last held in, human hands thousands of years ago.

Today, so long after they were created, no one can know for sure if the rock drawings were meant as messages for a distant future or whether they were intended to serve both pragmatic and spiritual purposes only for the people who created them.

Sandra Olsen, an American archaeologist who has studied the rock art at Jubbah and Shuwaymis in great detail, said some were perhaps territorial markers, while others may have been connected to the celebration of victories, the bounty of wildlife, the worship of long-forgotten gods or, in some cases, the product of the simple, essentially human need to leave a record of one’s existence — to affirm that “I was here.”

“As archaeologists, we mustn’t inflict our own cold, scientific, non-religious thoughts too much on what these people were doing, and we also shouldn’t try to over-interpret their religious beliefs,” she told Arab News.

“But I think it’s fairly safe to say that there are religious and spiritual purposes behind a lot of the art.”

US archaeologist Sandra Olsen on the secrets of Hail's rock art. (Richard T. Bryant)

At Shuwaymis and Jubbah, frozen in time, these ancient ones are shown herding camels and cattle and hunting prey including lion, leopard and ostrich, armed with bows and arrows and aided by domesticated hunting dogs, portrayed as restrained on leashes. These images, showing what appear to be Canaan dogs, an originally wild and hardy breed tamed in ancient times by the Bedouin and still in existence today, are believed to be the oldest visual representation of humankind’s working relationship with “man’s best friend.”

There are also images of dancers, which, to Olsen’s delight, seemed to come alive when she and her team began using a range of different techniques to photograph the rock art between 2009 and 2011.

“We did half of our work at night, using a couple of different techniques, and when you focus the light just right you can see the images so much better at night than during the daytime.

“We had campfires, and when the firelight flickered on the rock art, it looked animated, like the figures were moving or dancing. It’s difficult to prove how the artists wanted their work to be seen, but I can tell you it’s much better seen by firelight than under a bright sun.”

One rock face at Jubbah bears witness to the adoption in the region of one of the key inventions of early humankind — the wheel, shown on a horse-drawn chariot and depicted not in profile, but as a schematic viewed from above.

This, Olsen believes, may have been a warning to outsiders. “It’s a style that is found from Sweden to Mongolia, all across the Eurasian steppes and down into Central Asia, India, North Africa and Arabia. I think it’s shorthand that means ‘This is our territory. We have chariots, we’ve conquered this land, and you’d better watch out.’”

But much of the art, she believes, was about celebrating and maintaining traditions. “You have to think about where they were located,” she said. “Some were placed like billboards, so everyone could see them. Others are in little niches, off the beaten path and perhaps more secret.”

In either case, much time and effort would have been dedicated to the creations, executed during a period in history when merely surviving would have been a full-time job. Intriguingly, said Olsen, there are also half-finished pieces, which seem to indicate that the artists behind them “sometimes just had to get up and leave and never quite got back to that spot.”

The fate of the artists who failed to return to their unfinished work can never be known. “Usually they would have returned, they would have traveled on certain routes, following large herds of animals through their migrations because they were hunters or because they had sheep, goats and cattle, and they had to move with them all the time.”

Although of course familiar to Bedouin tribespeople since time immemorial, the ancient carvings at Jubbah have only been known to antiquarians since their accidental “discovery” in the 19th century by two of the first Western travelers to visit the oasis. In 1879, Lady Anne Blunt, founder of an Arabian horse stud in England, passed through Jubbah with her husband, Wilfrid, on their way to purchase steeds in Hail.

Lady Anne Blunt, who came to Hail in 1879 with her husband Wilfrid in search of Arab steeds for their stud in England, was the first westerner to record the rock art at Jubbah. (Alamy)

On the rocks above the town, Wilfrid, an amateur archaeologist searching for evidence of early inscriptions, found instead what his wife dismissed in a memoir as “a few of those simple designs one finds everywhere on the sandstone, representing camels and gazelles.”

Those “simple designs” would later be recognized by UNESCO as being part of “the biggest and richest rock art complexes not only in Saudi Arabia, but in the Arabian Peninsula and the Middle East generally,” comparable with “the most fascinating and largest rock art sites of the world.”

According to Robert Bednarik, an Australian archaeologist and rock-art expert who worked with and co-authored a number of papers with Dr. Majid Khan and who visited the Shuwaymis site within months of its discovery, its 8,000-year-old Neolithic panels “are among the most spectacular rock art in the world.”

Indeed, as he wrote in the newsletter of the Australian Rock Art Research Association shortly after the Saudi sites were inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2015, “the most outstanding Neolithic rock art known, comprising many thousands of painstakingly made magnificent figures, is that of the Shuwaymis sites.”

Although there is at least one larger complex among the 2,000 or more rock-art sites in Saudi Arabia, stretching from 50 to 130 kilometers north of the city of Najran, in the Kingdom’s southwest, “in terms of visual grandeur, Shuwaymis is unsurpassed.”

Remarkably, the secrets carved into rocks at Jabal Al-Manjor and Jabal Raat near the village of Shuwaymis remained unknown even to the Saudi authorities until 2001 — a testimony to the remoteness of their location in the inaccessible Harat Khaybar lava fields on the eastern flanks of the Hejaz mountain range.

The story of the discovery of what is now recognized as one of the largest and most important collections of ancient rock art in the world was told in a 2002 edition of Aramco World.

In March 2001, a Bedouin told local schoolteacher Mahboub Habbas Al-Rasheedi about rock carvings he had seen while grazing his camels. Al-Rasheedi and his brother spent days exploring the area and “stumbled into a proliferation of rock art tableaux,” including images of humans, cheetahs, hyenas, dogs, cattle, ibex, horses, camels and ostrich.

The story, said Khan, is correct. “I met the Bedouin, Al-Rasheedi and the director of archaeology in the Hail region, who took us to the sites for further investigations and research,” he said.

What that revealed, according to a range of dating techniques, including analysis of the patina that forms on rocks over vast periods of time and the cultural artifacts found at the sites, was that “Shuwaymis is the oldest rock art site in the Kingdom, dating from 14,000 years before the present time.”

For Khan, who has visited and worked on both sites many times, “it was the most emotional moment of my 40 years of research when the sites were registered on the World Heritage list.”

Many rocks, such as this one near Shuwaymis, carry images of the bezoar, a wild goat that is rare in Arabia today but was once common across the peninsula. (Saudi Tourism)

Many rocks, such as this one near Shuwaymis, carry images of the bezoar, a wild goat that is rare in Arabia today but was once common across the peninsula. (Saudi Tourism)

Lady Anne Blunt, who came to Hail in 1879 with her husband Wilfrid in search of Arab steeds for their stud in England, was the first westerner to record the rock art at Jubbah. (Alamy)

Lady Anne Blunt, who came to Hail in 1879 with her husband Wilfrid in search of Arab steeds for their stud in England, was the first westerner to record the rock art at Jubbah. (Alamy)

Graphic renderings by the artist Amanda Zimmerman bring out the details of the rock art. A figure known as The King and a warrior depicted at Jubbah. (Photos by Richard T. Bryant)

A hunter depicted with a bow and what might be a throwing stick at Jubbah.

This scene at Shuwaymis shows a man armed with a bow hunting with dogs.

This powerful carving at Jubbah shows a figure known as The Queen.

A Shuwaymis hunting scene is a reminder that lions once roamed a green Arabia.

AlUla: Hegra

Ancient city of the Nabataeans

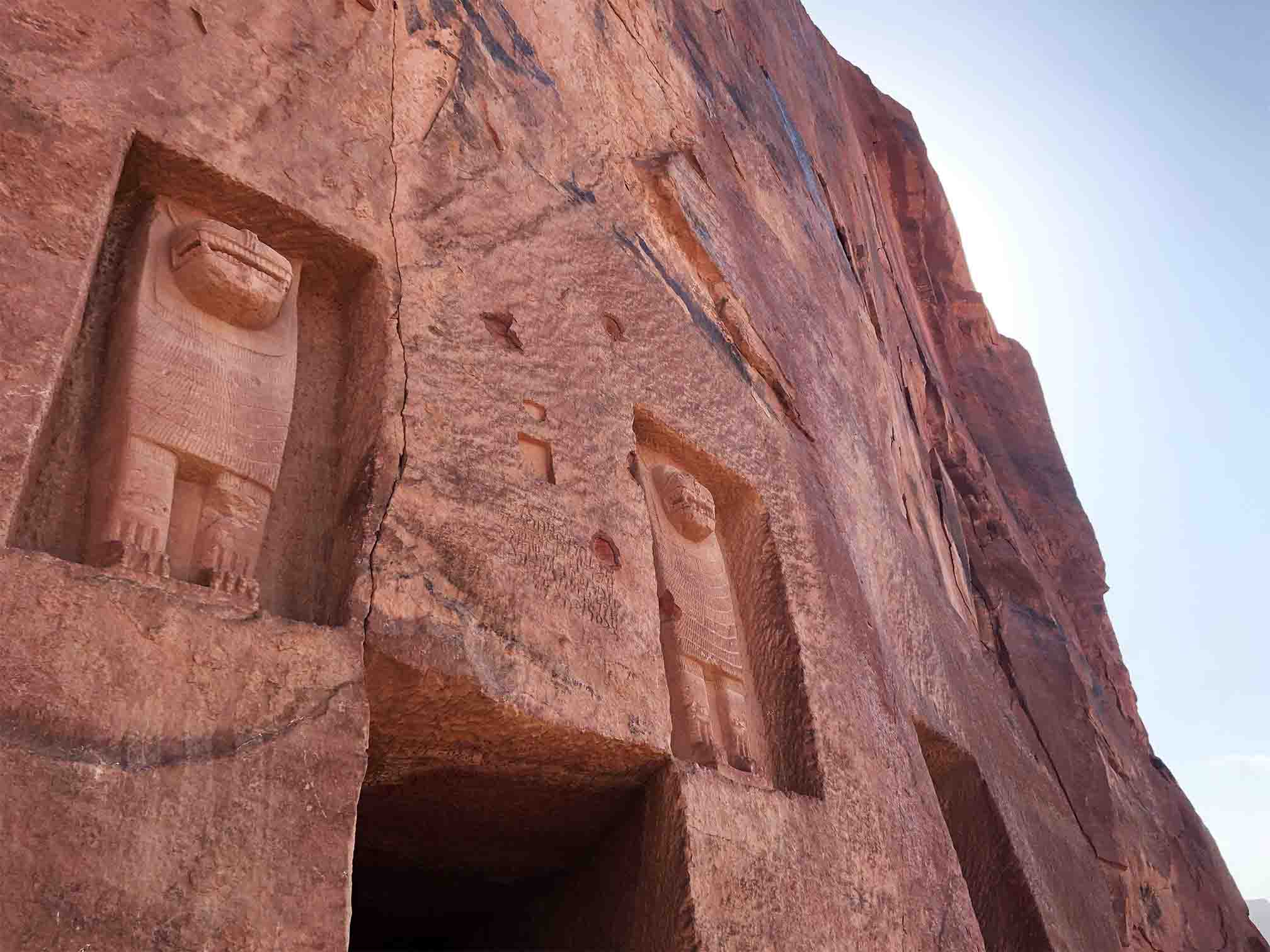

Petra, the ancient rock-carved city in modern-day Jordan, is famed throughout the world for its monumental ruins, left behind by the lost civilization of the Nabataeans.

But Petra tells only half the story of this mysterious people whose empire of trade at its peak 3,000 years ago dominated Arabia for about two centuries.

Like many countries, Saudi Arabia’s borders are currently closed because of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and are expected to stay closed until May 17. Before the outbreak, however, the Kingdom, long closed to the outside world, was in the process of opening up to global tourism. When the pandemic has passed, the world will be invited to travel 500 kilometers south from Petra to discover the wonders of Hegra, its sister city, carved from the rocks in a remote valley that was once at the crossroads of international trade.

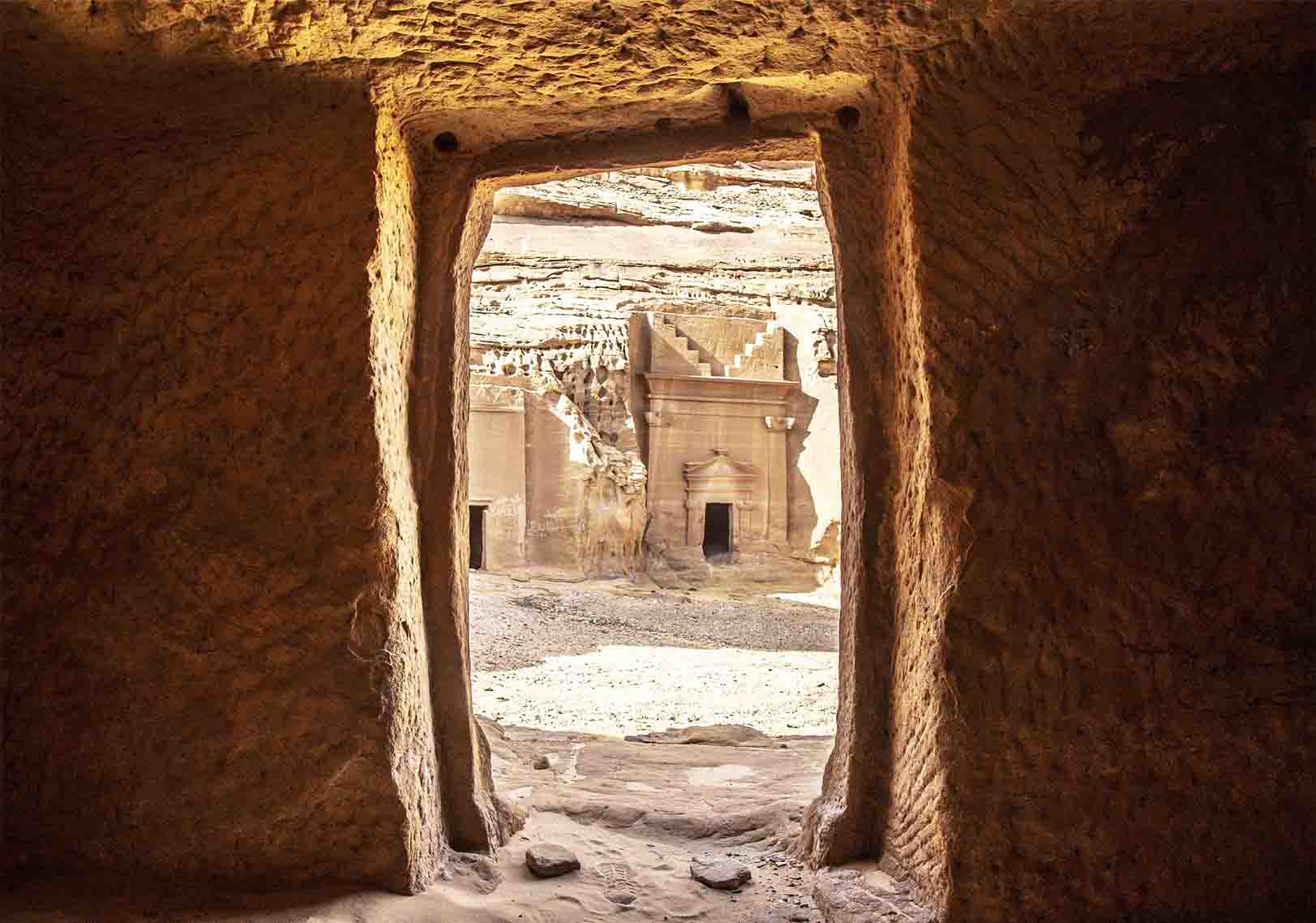

Some 200 kilometers inland from the Red Sea, Hegra is situated on a large plain southeast of the Hijaz Mountains, studded with hills of sandstone, isolated or grouped together to form massifs that have been dramatically sculpted by northwesterly winds, which have blown through the region every spring and early summer for millennia.

Of the 100 or more tombs carved into the rocks of Hegra, the majority are adorned with decorated facades while a third carry Nabataean inscriptions. (Saudi Ministry of Tourism)

In addition to creating the monumental canvases upon which the Nabataeans carved their story, the winds have also formed strange and evocative shapes, such as the three-story rock 10 kilometers northeast of the modern town of AlUla, sculpted over millions of years to resemble an elephant.

Most of the monuments and inscriptions visible at Hegra date from the first centuries B.C. and A.D. 75, but shards of pottery and other objects found recently at the site suggest that human settlement there began possibly in the third or second century B.C.

The earliest known historical reference to the Nabataeans was written in about 311 B.C. by Hieronymus of Cardia, a Greek general and contemporary of Alexander the Great who took part in a series of failed attempts to defeat them.

Hegra, a place of superstition avoided by the Bedouin, was later known as Madain Saleh — or the city of Saleh — a place associated with an account in the Qur’an of a vain attempt by the Prophet Saleh to convert the Thamudi, a tribe in the AlUla Valley, from their idolatrous ways.

Archaeologists believe that it was the perception of Hegra by the Bedouin as a cursed place, unsafe for settlement by the living, that over the centuries has helped to preserve much of its fabric.

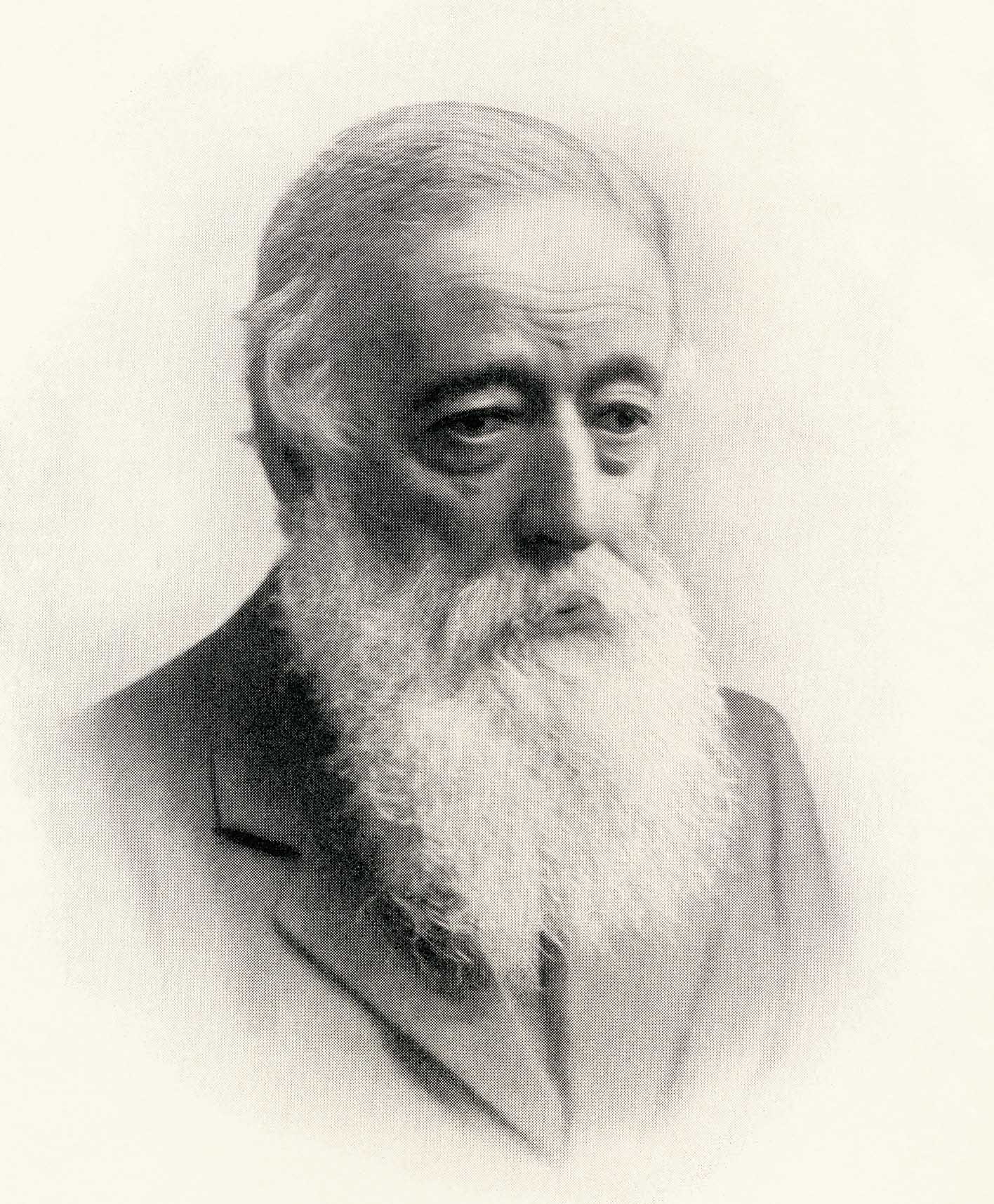

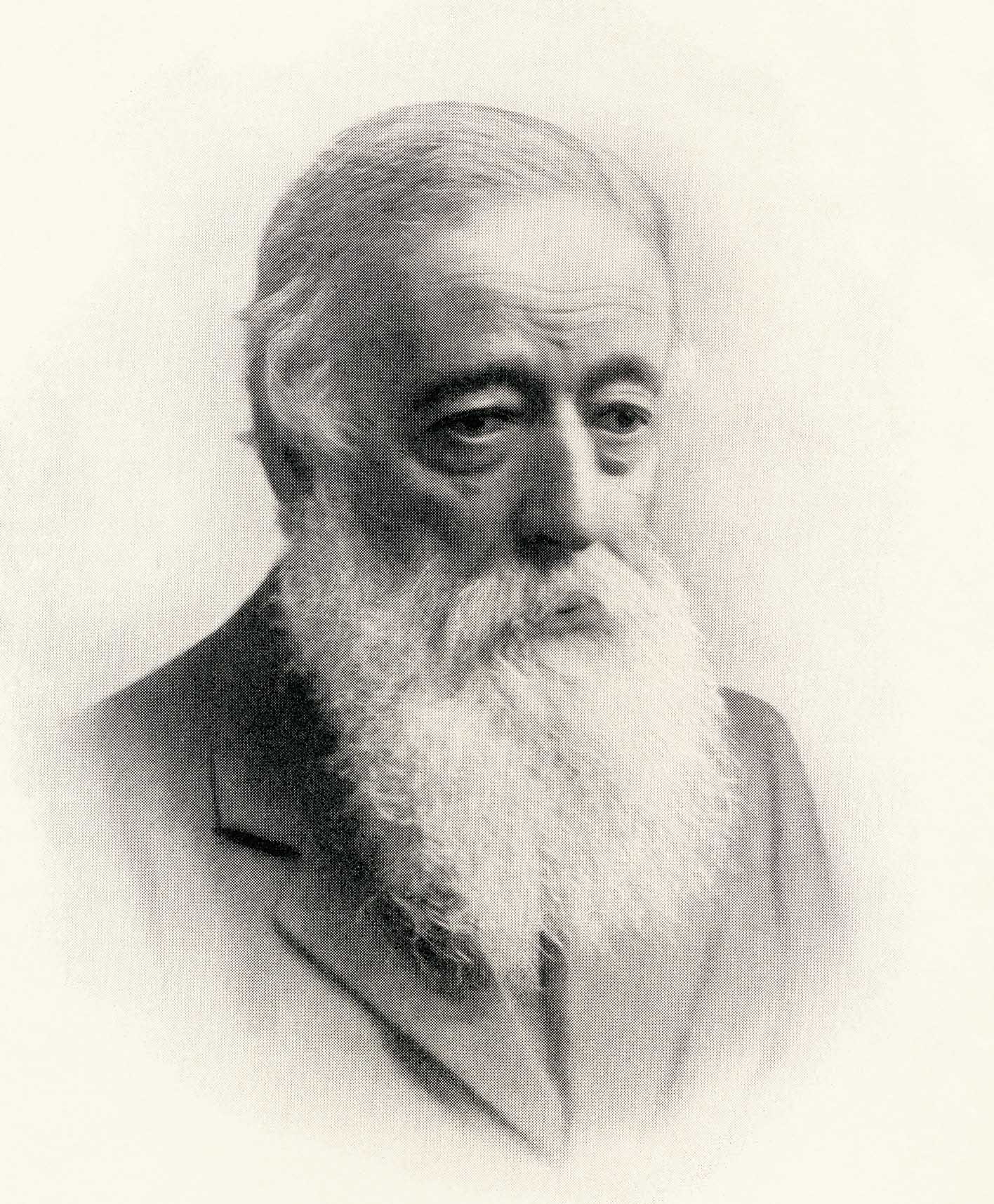

Hegra was “discovered” in the 1880s by the British explorer Charles Montagu Doughty, the first Westerner to visit the site. In his book “Travels in Arabia Deserta,” published in 1888, he recalled stumbling upon the lost monumental necropolis — a carved citadel of the dead, hewn out of the towering sandstone rock faces that surrounded the site of an old city.

British explorer Charles Montagu Doughty, the first Westerner to reach Hegra, recorded his impressions of the Nabataean tombs in his book “Travels in Arabia Deserta,” published in 1888. (Getty Images)

“Little remains of the old civil generations of el-Héjr, the caravan city,” Doughty wrote. “Her clay-built streets are again the blown dust in the wilderness. Their story is written for us only in the crabbed scrawlings upon many a wild crag of this sinister neighbourhood, and in the engraved titles of their funeral monuments, now solitary rocks, which the fearful passenger admires, in these desolate mountains.”

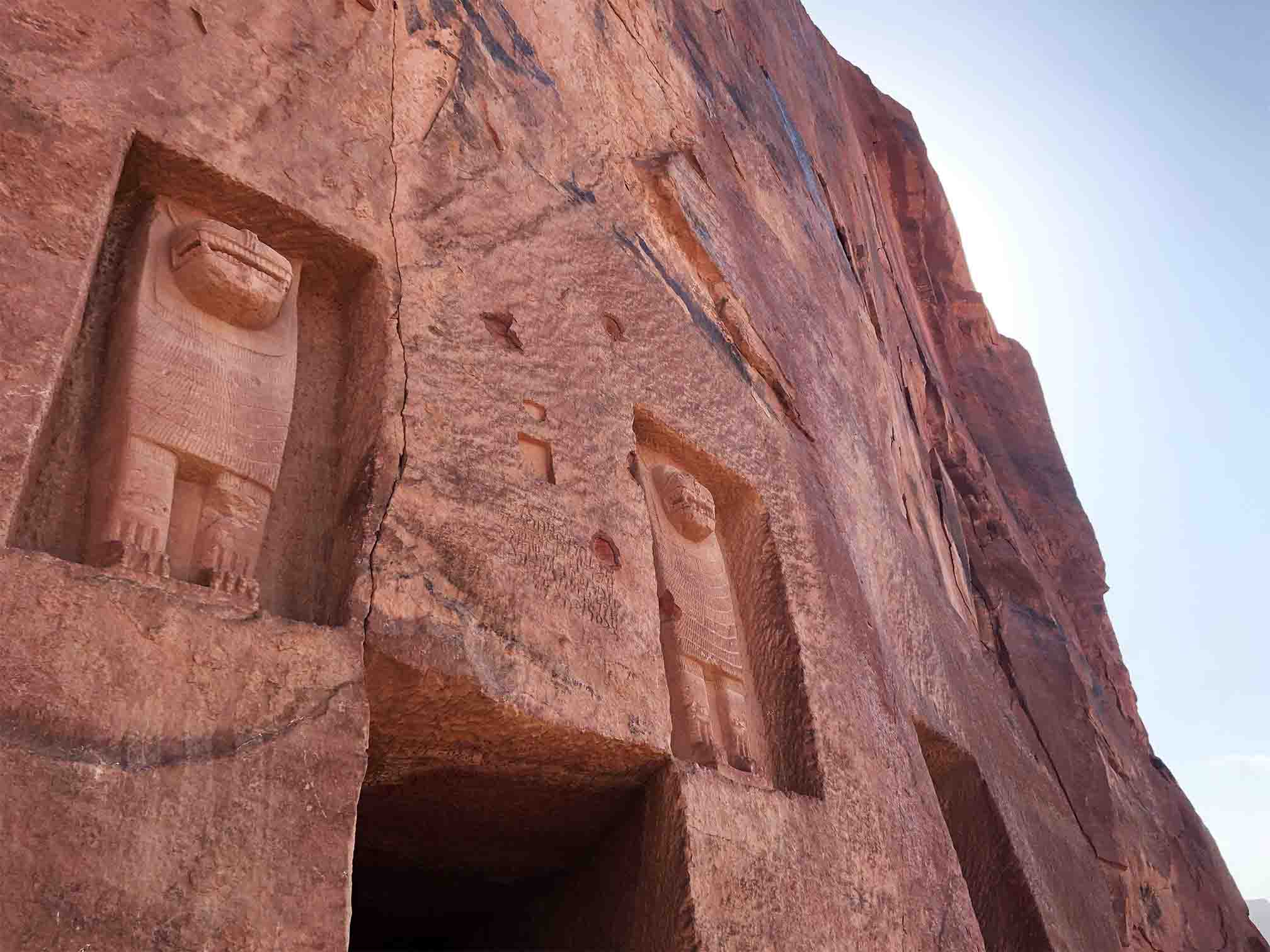

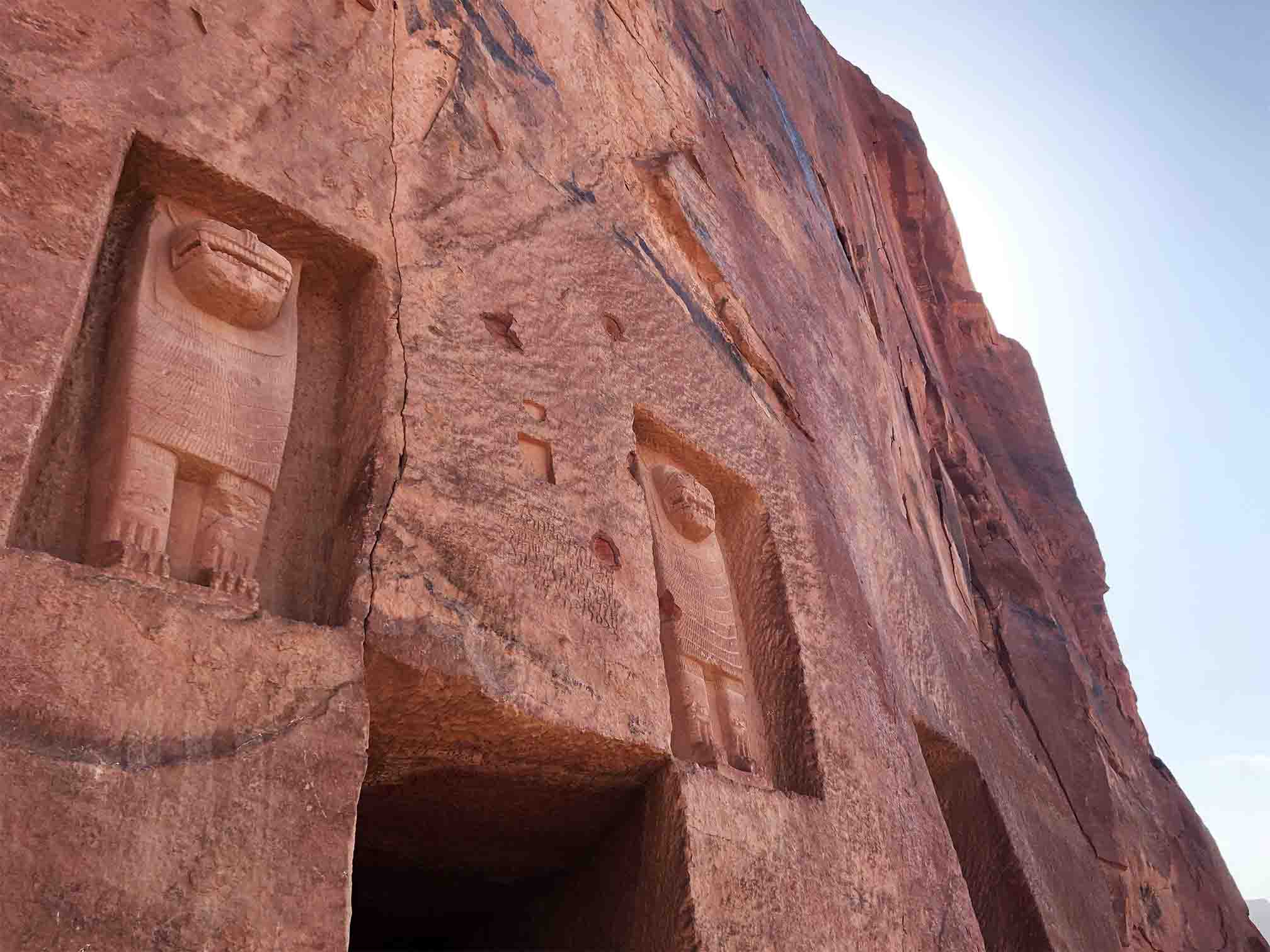

There are more than 100 monumental tombs carved out of the rocks at Hegra, dating from about the first century B.C. to A.D. 75. Of the four main necropoles, Qasr Al-Bint, home to 31 tombs, is visually the most dramatic, both from a distance and up close. The exterior facades of many of the tombs feature carved monsters, eagles, and other small, sculpted animals and human faces.

As at Petra, many of the tombs feature spectacular carved facades. However, unlike at Petra, many of the facades carry Nabataean inscriptions, in many cases naming the dead and offering a unique insight into the lives of the people who once called Hegra home.

Carved monsters, human faces, eagles and other small sculpted animals decorate some of the tombs at Hegra. (Saudi Ministry of Culture)

In addition to the rock tombs, more than 2,000 other burial places are scattered across the site.

Thirty-one tombs dating from A.D. 1 to 58 are carved into Qasr Al-Bint, one of the spectacular necropoles at Hegra. (Getty Images)

Close by is the Jabal Ithlib — at 100 meters, the highest sandstone outcrop on the site. Here there are no tombs, but this was nevertheless a religious area, studded with niches, altars and sacred stone carvings, many of which bear inscriptions. Hewn out of the interior of the rock is a “triclinium,” a three-sided room where worshippers would gather for ritual meals.

Carved monsters, human faces, eagles and other small sculpted animals decorate some of the tombs at Hegra. (Saudi Ministry of Culture)

Little can be seen today of the homes of the Nabataeans at Hegra. Made from sun-dried mud bricks, they have long disappeared beneath the sands, although geophysical surveys carried out between 2002 and 2005 revealed tantalizing evidence of underground structures. Parts of the city wall can still be made out.

Hegra is situated in a large plain studded with sandstone outcrops. The most impressive of these is Jabal Ithlib, an ancient religious site home to a series of sanctuaries, niches and altars carved out of the rock. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Since Doughty’s visit, Hegra has been little known outside of academic circles. But now, the trading center has been awakened from a 1,600-year slumber. After one of the most exhaustive archaeological investigations ever carried out, it will soon be welcoming visitors from around the world once again as the heart of a spectacular tourism development, focused on culture and heritage, that will restore the AlUla Valley to its ancient status as a global destination.

“Hegra was my introduction to Saudi Arabia,” said architect Simone Ricca, a heritage conservation expert who helped prepare Saudi Arabia’s successful application to have the city listed in 2008 as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In all, Ricca went on to work on the nominations for four of the Kingdom’s five UNESCO sites.

“I visited for the first time in 2006,” recalled Ricca, co-founder of Paris-based RC Heritage consultants. “Thanks to a pioneering effort by the Saudi antiquities department to survey and protect the country’s sites in the early 1980s, there was a protective fence around the site. But there was no one there then.

“It was an incredibly fascinating experience. I had been to Petra, and I had been living and working in the Middle East for a few years, but I didn’t know much about Saudi Arabia.”

Ricca had seen a photograph of one of Hegra’s tombs hanging on the wall of a UNESCO office but never imagined he would go there. Then one evening, with the rocks and the desert lit by the light of a full moon, he did.

“It was so exciting,” he said. “I had this feeling, admittedly naive, of discovering something. I know it is stupid and childish. But part of my work is the privilege of visiting places that are not yet well known, and this was incredible.”

Hegra features a stunning collection of well-preserved monumental tombs dating from the first century B.C. The site, which features some 50 inscriptions of the pre-Nabataean period and cave drawings, is also home to dozens of ancient water wells. It was these, tapped by the Nabataeans’ innovative hydraulic expertise, that in antiquity transformed the AlUla Valley into a thriving oasis, a vital artery of caravan trade in incense and spices from Yemen and India.

Farming continues in AlUla today, just north of Hegra, where modern farms rely on the same underground water supplies that sustained the Nabataeans and even continue to use some of the old wells.

Mystery surrounds the origins of the Nabataeans, a people who for 400 years commanded a vast kingdom that in size and scope foreshadowed that of Saudi Arabia and whose written language was one of the final steppingstones in the evolution of Arabic. There is no mention of them in any written source before they first appeared in the account by Hieronymus of Cardia in 311 B.C.

Although most of the tombs at Hegra were carved and used between the first and early fourth centuries, occupation of the site dates from about the fourth century B.C. There is growing evidence that the Nabataean presence at Hegra may have continued in some form well into the fourth century, but their grip on the region and its profitable trade routes was ended suddenly in A.D. 106, when the whole of their territory was overrun by the legions of Emperor Trajan and subsumed into the Roman province of Arabia Petraea. There is no mention of them in any written source before they first appeared in the account by Hieronymus of Cardia in 311 B.C.

Inside one of Hegra's many tombs. One, at Jabal Al-Ahmar, dates to A.D. 60 and was built for “Hinat daughter of Wahbu ... and for her children and her descendants forever ... In the twenty-first year of King Maliku, King of the Nabataeans.” It was found to contain the remains of more than 80 people. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Until the recent archaeological investigations at Hegra and throughout the wider AlUla Valley, there was no evidence to suggest that Rome’s influence in Arabia had extended much further south than the mouth of the Gulf of Aqaba on the Red Sea. But the discovery of a fortified Roman camp on the southern boundary of the ancient city is just part of the astonishing story that has emerged over the past decades, thanks to the work of a joint Saudi-French archaeological team whose trowels have swept away the sands of time that had obscured the world heritage treasure that is Hegra for two millennia.

The discovery, said Ricca, had redrawn the map of the Roman empire.

“No one knew that the Roman presence extended so far south in Arabia. The discovery of the fortress has added to the understanding that ancient Saudi Arabia was not an isolated place but part of the wider world.”

The AlUla Valley is home to a second fort, a reminder of another empire that came and went in Arabia. Between 1744 and 1757, the Ottomans built a fortress there to protect travelers on the old pilgrims’ route to Makkah from Damascus and beyond, which passed through the valley. The fort was built near the well of Bir Al-Naqa, where pilgrims used to halt on their way to and from Makkah along the Syrian pilgrimage route.

Nearby is a railway station, a stop on the Hejaz railway built by the Ottomans that ran 1,300 kilometers from Damascus to Madinah. Work began in 1901, and the railway opened in 1908, but it fell into disuse after the First World War, during which it was repeatedly attacked by Lawrence of Arabia and the Arab warriors rebelling against Ottoman rule.

Hegra is also home to a station and the remains of the old Hejaz railway, built by the Ottomans to transport pilgrims from Damascus to Madinah. Opened in 1908, it was abandoned after being repeatedly attacked during the First World War. (Getty Images)

The remains of carriages and locomotives, blown off the tracks during the war, can still be seen in the desert. The restored station complex at AlUla now houses a museum and facilities for visitors.

In the words of the UNESCO document, the Hejaz railway “is historically important for both Arab and Turkish history as it marked the beginning of Arab autonomy and the end of the Ottoman Empire.”

Although not part of the UNESCO listing, other fascinating sights await visitors to the AlUla Valley. Some 20 kilometers south of Hegra are the ruins of the old town of AlUla, a complex of narrow passageways and now mainly roofless buildings, made of mudbrick and stone. Finally abandoned in the 1980s, this ghost town of some 900 tightly packed houses was for hundreds of years a bustling waypoint on the pilgrimage route to Makkah.

On its doorstep is the ancient city of Dadan, situated on the edge of a lush oasis of palm trees, where inhabitants of the old town would go to escape the heat during the summer months. The stone-built capital of the Dadan and later Lihyan kingdoms is believed to date back to between the late ninth and early eighth century B.C.

In 1326, the famed Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta journeyed through old AlUla town on camelback. His reflections on the hospitality of the people of AlUla are recalled on a modern sign on the town’s ancient watchtower. AlUla, he wrote, “is a large and fine village with orchards, dates, palms and water. The pilgrimage caravan stays there for four days to resupply and wash.

“Pilgrims leave any excess belongings they might have with the townspeople who are known for their trustworthiness and only take with them what they need.”

The abandoned city of AlUla occupies a significant place in the story of Islam. It is believed that in 630, the Prophet Muhammad passed through the town on his way from Madinah to the Battle of Tabuk.

Although it is not clear when the town was first built, it certainly dates back to the 13th century and was inhabited until 1983, the year the last family left for the new and modern town of AlUla nearby.

The whole of Hegra’s past is to play a vital role in the future of the AlUla Valley. The Royal Commission for AlUla, established in 2017, is working in partnership with Afalula, the French Agency for AlUla Development, founded in Paris in July 2018 with the mission “to support its Saudi partner in the transformation of the AlUla region into a worldwide cultural and touristic destination.”

In an interview in February 2019, Amr Al-Madani, CEO of the Royal Commission for AlUla (RCU), described the plan for AlUla as “one of the Kingdom’s flagship projects,” designed “to promote the heritage of this region, to transform AlUla into one of the country’s cultural capitals.”

It is the vision of the commission and its French partner that AlUla will be transformed into a “living, open museum,” complete with a unique network of museums, archaeological sites and luxury hotels.

In addition to the treasures of Hegra, AlUla will offer visitors resorts, hotels and other world-class facilities. About a 45-minute drive from Hegra is the Sharaan Nature Reserve, a 925-square-kilometer territory within AlUla county that features some of the region’s most striking rock formations and desert habitats. The reserve will be home to several luxury resorts, including one designed by the French architect Jean Nouvel, whose creations include the Louvre Abu Dhabi, and another by Jordanian architect Omar Al-Omari.

Another luxury hotel operator destined for AlUla is Aman Resorts and Hotels, which will open three eco-focused resorts in the region by 2023. One will be a luxury tented camp, another an interpretation of a desert-style ranch, and the third will be situated close to AlUla’s heritage sites.

Elsewhere is the Maraya Concert Hall, a giant mirrored cube designed by Studio Gio Forma. In addition to its role as a concert venue and exhibition center, Maraya, which means “reflection” in Arabic, is a mesmerizing piece of art in its own right, its mirrored walls designed to create a visual extension of the breathtaking AlUla landscape.

The protected site of Hegra lies within the AlUla Valley, which is being developed as a major cultural tourism destination, featuring resorts, festivals and the spectacular Maraya Concert Hall, the world's largest mirrored building. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Art and cultural initiatives are central to AlUla’s vision, as typified by the Winter at Tantora festival, an annual event suspended during the pandemic. The festival, which derives its name from a sundial located in the old town of AlUla, was staged for centuries by the locals to mark the changing of the seasons. In December 2018, it returned, greatly magnified, with a series of concerts over eight weekends featuring world-class musicians, revealing the destination of AlUla to the rest of the world. The RCU also commissioned artists to create public artworks in the old town inspired by AlUla.

As it shone in antiquity, so the AlUla region and its architectural treasures are now part of a bright future, for Saudi Arabia and the wider world.

“AlUla is an opportunity for the entire globe,” said Al-Madani. “It is a site for the development of knowledge, not just for Saudi Arabia but the entire international community.”

Just as the caravans of antiquity once came to trade in this land, so AlUla, ancient Hegra reborn, will again attract travelers from all corners of the world.

For Saudi Arabia, the rediscovery of its shining past is a golden opportunity to embrace a bright future.

Of the 100 or more tombs carved into the rocks of Hegra, the majority are adorned with decorated facades while a third carry Nabataean inscriptions. (Saudi Ministry of Tourism)

Of the 100 or more tombs carved into the rocks of Hegra, the majority are adorned with decorated facades while a third carry Nabataean inscriptions. (Saudi Ministry of Tourism)

British explorer Charles Montagu Doughty, the first Westerner to reach Hegra, recorded his impressions of the Nabataean tombs in his book “Travels in Arabia Deserta,” published in 1888. (Getty Images)

British explorer Charles Montagu Doughty, the first Westerner to reach Hegra, recorded his impressions of the Nabataean tombs in his book “Travels in Arabia Deserta,” published in 1888. (Getty Images)

Thirty-one tombs dating from A.D. 1 to 58 are carved into Qasr Al-Bint, one of the spectacular necropoles at Hegra. (Getty Images)

Thirty-one tombs dating from A.D. 1 to 58 are carved into Qasr Al-Bint, one of the spectacular necropoles at Hegra. (Getty Images)

Carved monsters, human faces, eagles and other small sculpted animals decorate some of the tombs at Hegra. (Saudi Ministry of Culture)

Carved monsters, human faces, eagles and other small sculpted animals decorate some of the tombs at Hegra. (Saudi Ministry of Culture)

Hegra is situated in a large plain studded with sandstone outcrops. The most impressive of these is Jabal Ithlib, an ancient religious site home to a series of sanctuaries, niches and altars carved out of the rock. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Hegra is situated in a large plain studded with sandstone outcrops. The most impressive of these is Jabal Ithlib, an ancient religious site home to a series of sanctuaries, niches and altars carved out of the rock. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Inside one of Hegra's many tombs. One, at Jabal Al-Ahmar, dates to A.D. 60 and was built for “Hinat daughter of Wahbu ... and for her children and her descendants forever ... In the twenty-first year of King Maliku, King of the Nabataeans.” It was found to contain the remains of more than 80 people. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Inside one of Hegra's many tombs. One, at Jabal Al-Ahmar, dates to A.D. 60 and was built for “Hinat daughter of Wahbu ... and for her children and her descendants forever ... In the twenty-first year of King Maliku, King of the Nabataeans.” It was found to contain the remains of more than 80 people. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Hegra is also home to a station and the remains of the old Hejaz railway, built by the Ottomans to transport pilgrims from Damascus to Madinah. Opened in 1908, it was abandoned after being repeatedly attacked during the First World War. (Getty Images)

Hegra is also home to a station and the remains of the old Hejaz railway, built by the Ottomans to transport pilgrims from Damascus to Madinah. Opened in 1908, it was abandoned after being repeatedly attacked during the First World War. (Getty Images)

The protected site of Hegra lies within the AlUla Valley, which is being developed as a major cultural tourism destination, featuring resorts, festivals and the spectacular Maraya Concert Hall, the world's largest mirrored building. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

The protected site of Hegra lies within the AlUla Valley, which is being developed as a major cultural tourism destination, featuring resorts, festivals and the spectacular Maraya Concert Hall, the world's largest mirrored building. (Royal Commission for AlUla)

Al-Ahsa: Oasis

An earthly paradise

The challenge for the casual visitor to Al-Ahsa is, quite literally, to see the forest for the trees.

There are, after all, more than 2.5 million palm trees in the world’s largest and almost certainly oldest oasis. And, with the UNESCO World Heritage site composed of no fewer than 12 separate elements, scattered over a total area of 85 square kilometers, at first glance this “serial cultural landscape,” which “preserves material traces representative of all the stages of the oasis history, since its origins in the Neolithic to the present,” defies quick and easy appreciation.

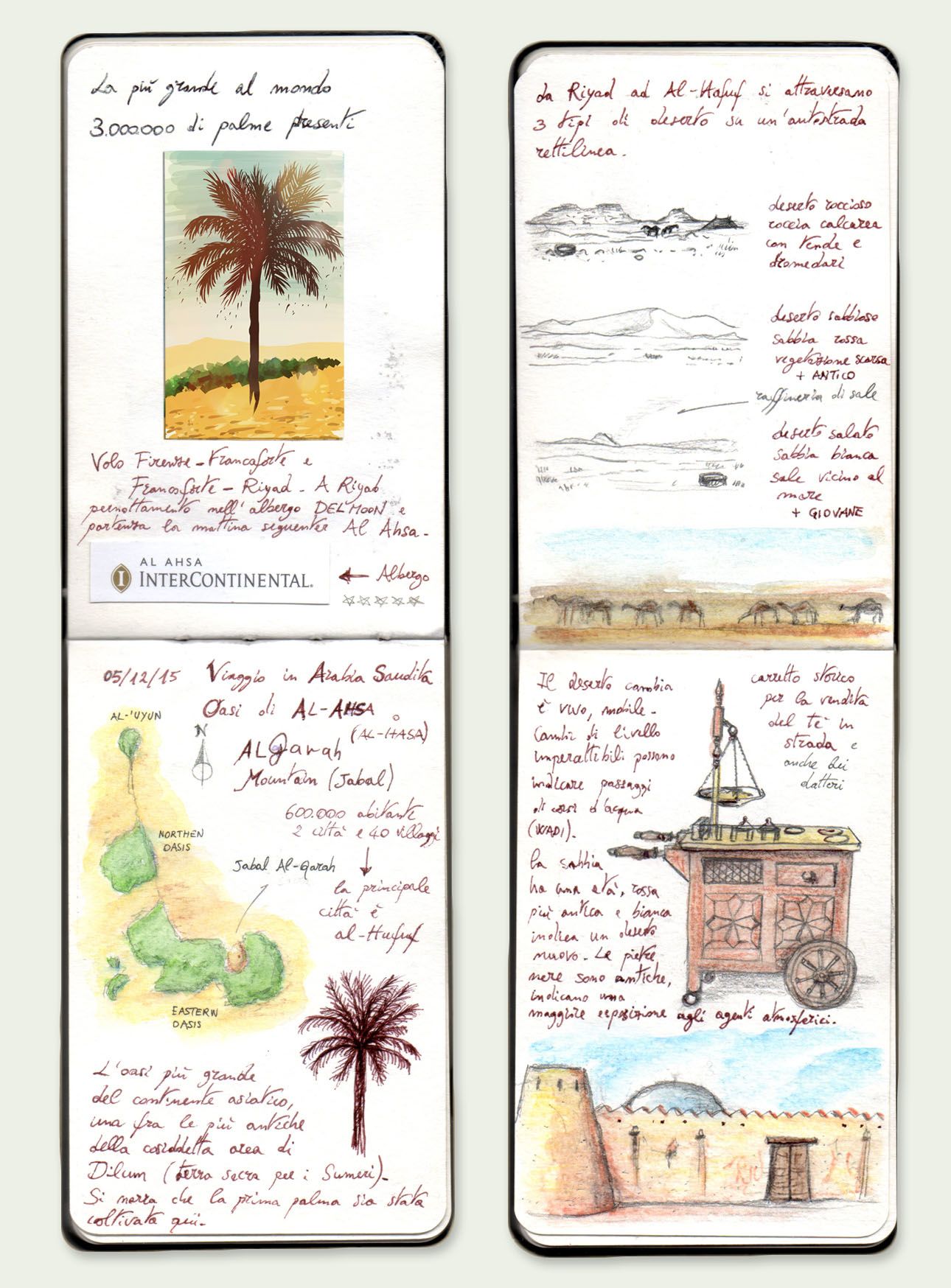

For Panaiotis Kruklidis, an Italian architect specializing in cultural heritage who, in 2015 and 2016, was part of the team of experts drafted in to prepare the nomination document that saw the site listed in 2018, the key was to seek a higher perspective.

“We certainly understood the details of the oasis, the organization of its individual plots, but we still couldn’t grasp its overall magnificent size,” he recalled.

“We only discovered it on the day when we decided to climb Jabal Al-Qarah, the hill in the center of the oasis that was probably sacred to the first inhabitants of the place, who had settled among its caves.”

From this vantage point, “it was finally possible to admire the greatness of the oasis as a whole.”

An aerial view of part of the oasis taken in 1965. (Saudi Aramco)

With maps and notebooks in hand and gazing down on the vast geometry of palm groves, gardens and waterways, the team was “able to follow the intricate water system, the lifeblood for every element of the oasis, made up of springs, channels of clean water and drainage.” For Kruklidis, the patterns evoked “the natural geometry of leaves, made up of main and secondary veins.”

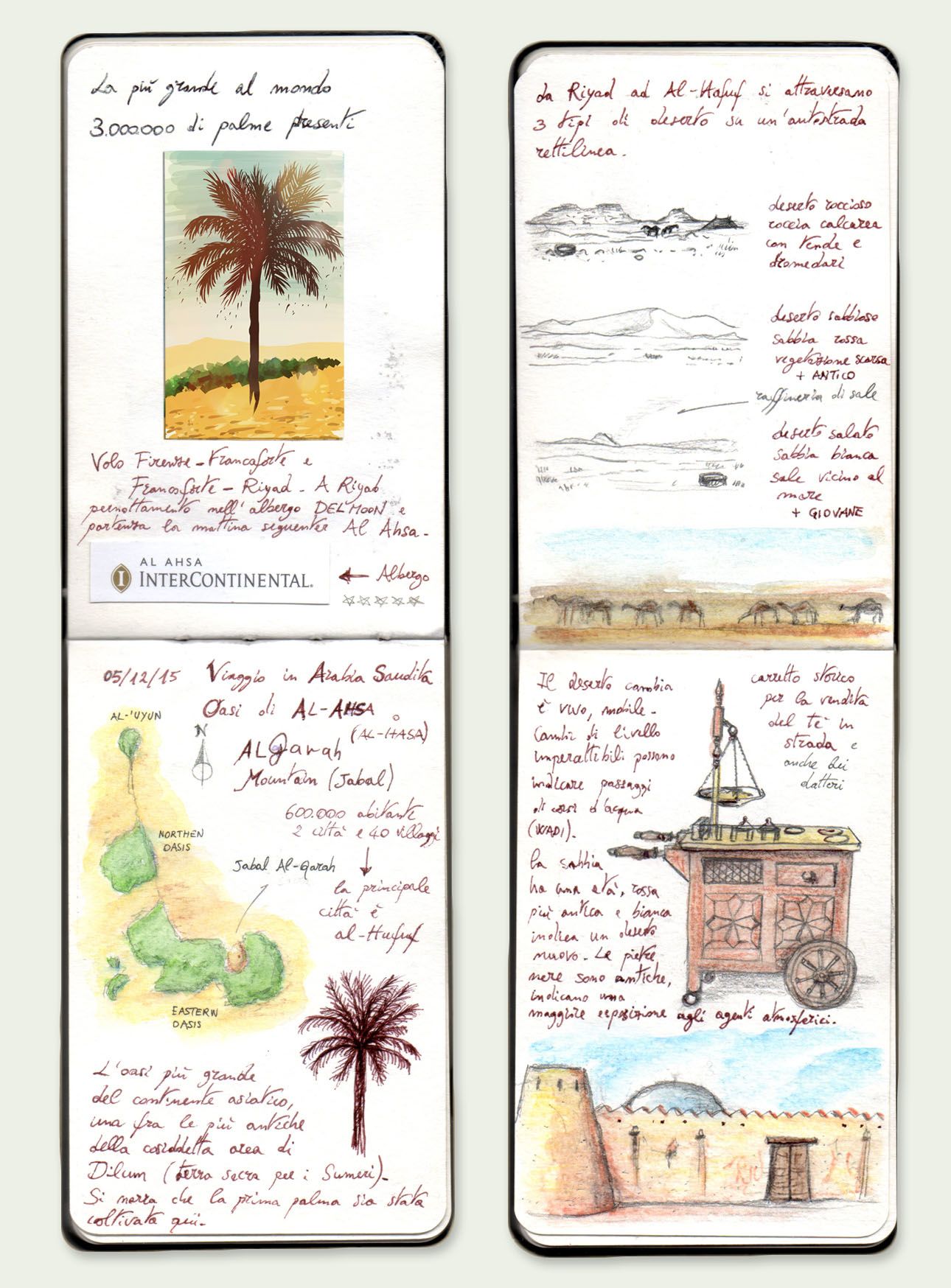

Sketches from the notebook of Panaiotis Kruklidis, an Italian architect who helped to prepare the document nominating Al-Ahsa as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Then, Kruklidis and his colleagues set about exploring the oasis at ground level and quickly discovered the beauty of a place in which some scholars believe the date palm was first farmed by human beings.

Al-Ahsa is associated with the Dilmun civilization that flourished in the third millennium B.C in what is now eastern Saudi Arabia. It has also been identified by some archaeologists as the possible site of the near-mythical Sumerian paradise — the garden of the gods where, some 4,800 years ago, the legendary hero King Gilgamesh of Uruk sought the tree of life. The archaeological remains of Uruk, another World Heritage Site, are situated east of the Euphrates River in what is today southern Iraq, some 750 kilometers northwest of Al-Ahsa.

“We decided to ‘get lost’ in the great oasis and entered a private garden, which stood out for the considerable height of its palm trees,” recalled Kruklidis. The first thing they noticed was “the care with which a passionate farmer had maintained his garden. The ancient knowledge of traditional methods, handed down from generation to generation, reflected the charm of myth and time.”

Evening was approaching and the low light that filtered through the palms, casting long shadows and dancing on the surface of the water, began to throw details into sharp relief. Kruklidis, part of whose role was to document key elements of the oasis with drawings, was struck by “the variety of colors of the fruit on the trees, the background of a fragile and fragrant green and the light playing on the water, recalling the labyrinthine waterways and fountains of a distant and almost mythical period.

“It was like seeing the garden of the gods, still standing in Dilmun’s time.”

Kruklidis had no difficulty believing that “it was probably from here that the idea, the image, of the terrestrial paradise, as we know it, developed.”

Heritage conservation expert Simone Ricca, who worked on the nomination documents for four of Saudi Arabia’s five UNESCO sites, including Al-Ahsa, said the oasis is “the most complex site to conceptually understand and to grasp.”

Listed by UNESCO as “an evolving cultural landscape,” it is “the product of the interaction between man and nature. Oases are not a natural feature, they are manmade, so they are a perfect example of this concept of a cultural landscape.”

The palm groves at Al-Ahsa are, according to the UNESCO nomination document, “among the largest at the global scale.” They also preserve the historical characterstics of systems based on “traditional techniques remained unchanged...for thousands of years.” (Saudi Ministry of Tourism)

Occupied for at least 8,000 years, Al-Ahsa has seen and survived the rise and fall of great powers over the ages, enduring and outliving all comers, including the Chaldeans, the Achaemenids, Alexander the Great and the Roman and Ottoman empires.

Importantly, and unlike many UNESCO sites that are little more than fragmentary ruins frozen in time, Al-Ahsa has been continuously occupied and continues to thrive and evolve.

“Even the new drainage and water-management systems that have been created since the 1980s are part of this evolving concept,” said Ricca.

“What is amazing is that we still have two and a half million palm trees there, and we also have almost 2 million people living in Al-Ahsa.

“This interaction is intellectually challenging and interesting. For the tourist, it might not be visually so obvious to grasp, but it is central to this concept of the evolving cultural landscape.”

The UNESCO property includes three oases fed by a system of dozens of ancient springs and wells, three castles, the traditional palm-grove village of Al-Oyoun, the historic Qasariyah Market, the Jawatha Mosque, two protected archaeological sites and the 21-square-kilometer mangrove-fringed Al-Asfar Lake, a large and historic body of water into which the waters from the Eastern Oasis drain via an 18-kilometer canal. Al-Asfar has become a unique natural ecosystem and in 2019 was declared a national nature reserve by Saudi Arabia.

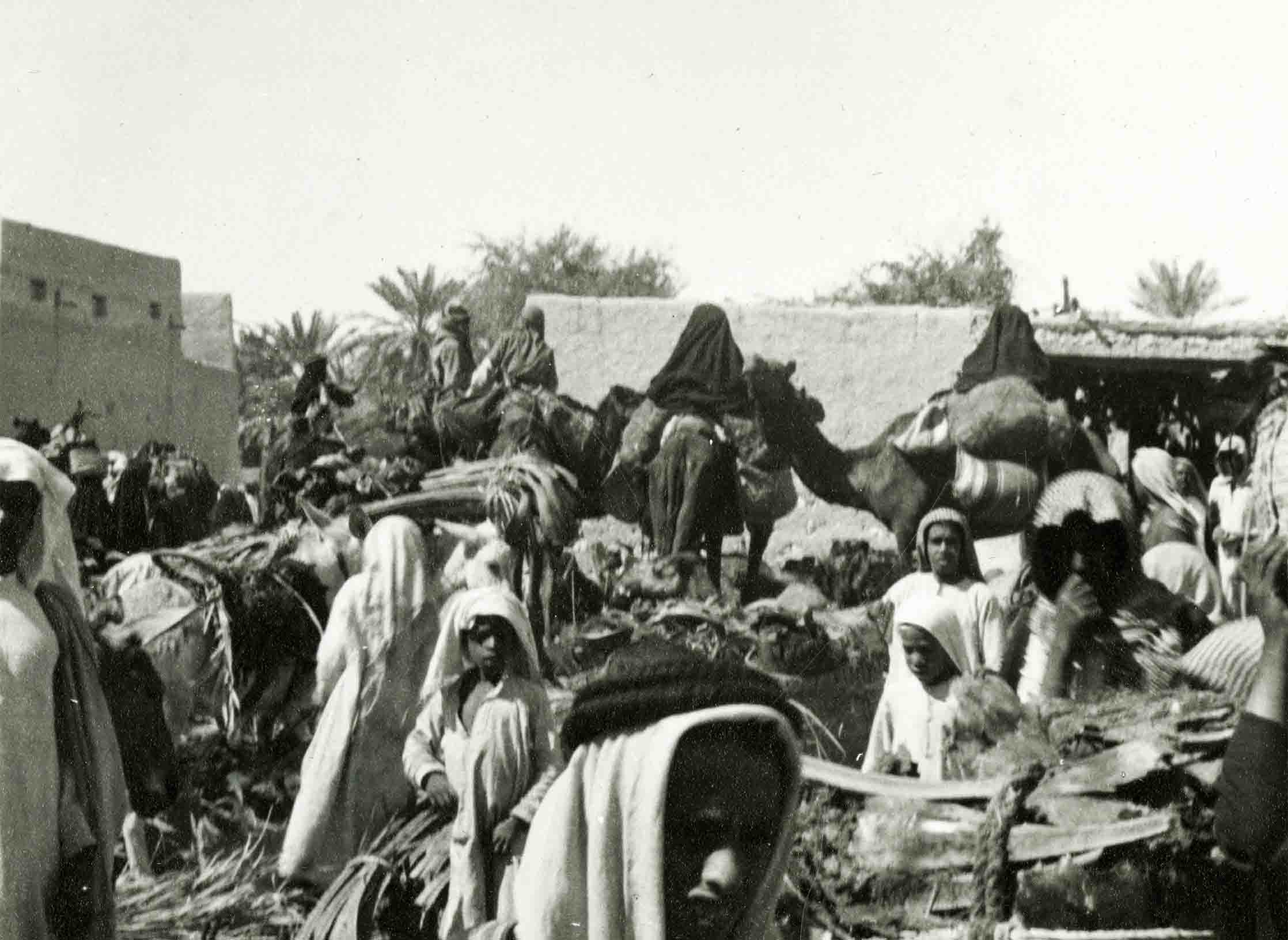

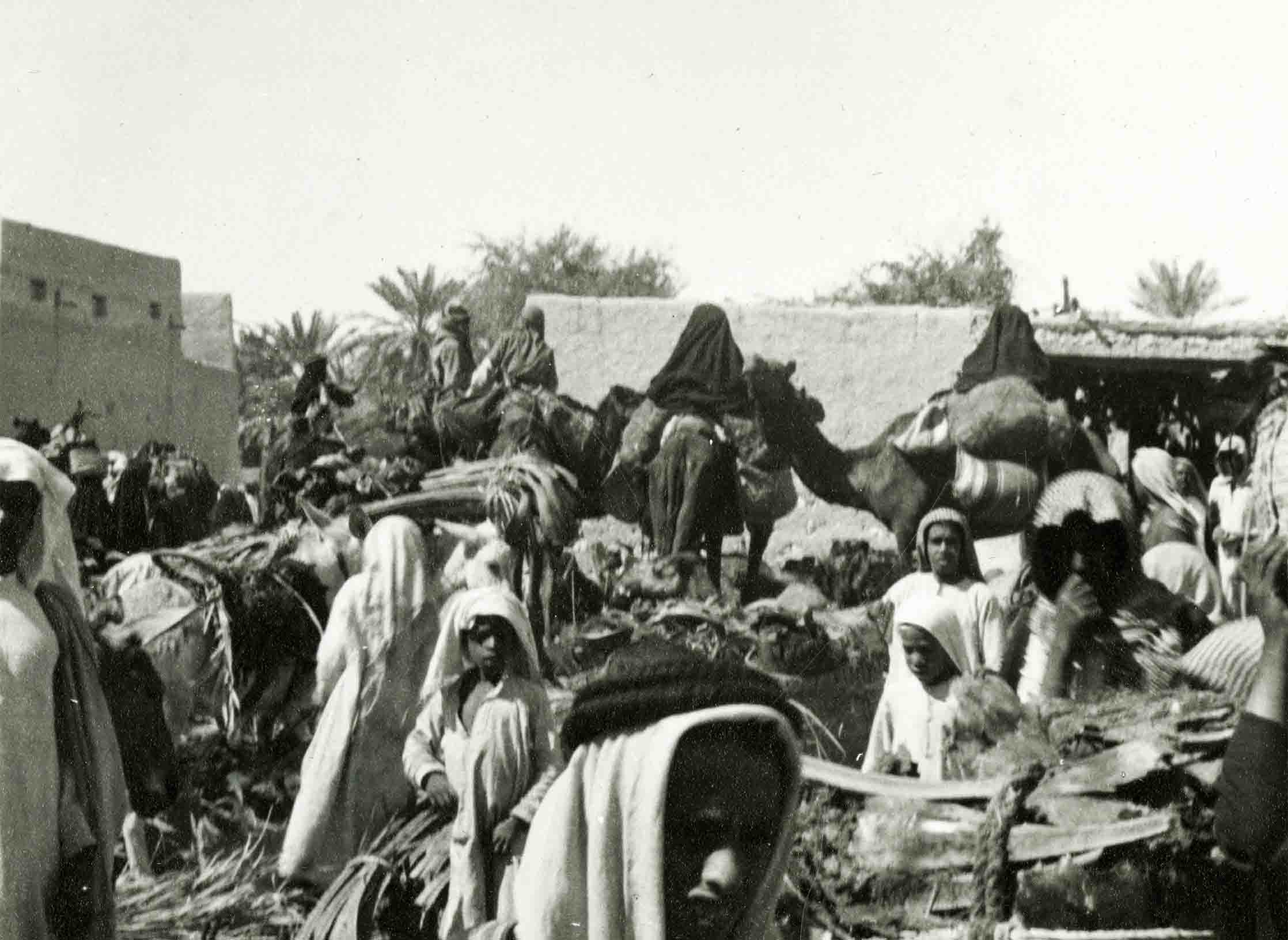

A bustling marketplace at Al-Ahsa Oasis, captured in this 1937 photograph by Geraldine Rendel, the wife of a British diplomat and the first European woman to be received in public by Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia. (Middle East Center Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford)

The largest of the 12 components is the Eastern Oasis, a roughly crescent-shaped concentration of dense palm groves and gardens over 38 square kilometers, extending 9 kilometers from north to south and 12 kilometers east to west and watered by an intricate network of canals. At its center is the rocky outcrop known as Jabal Al-Qarah, the summit of which affords stunning views of the surrounding sea of green. To the northwest is the 20-square-kilometer Northern Oasis, which shelters a number of historic villages.

Al-Ahsa lies between the rock desert of Al-Ghawar to the west and the sand dunes of the Al-Jafurah desert to the east. It owed its settlement in antiquity and its continued existence today to the plentiful water provided by the springs of Al-Ghawar, a region that in modern times has provided Saudi Arabia with another natural bounty. Just as Al-Ahsa is the largest oasis in the world, so Al-Ghawar is the world’s largest oil field.

For centuries, the oasis of Al-Ahsa has been under threat from the shifting sands of the Al-Jafurah desert, pressing in from the north, east and south. According to the UNESCO nomination document, “the sands surrounding the oasis, due to the periodically strong north, north-west and southern winds, are mobile and have been encroaching upon the cultivated land and endangering the oasis for many centuries.”

For the past thousand years, humans have had to fight to preserve the oasis, part of which nevertheless “has been covered by an active sand dune field advancing southward, along a 12 km large front.” This dune has “notably covered earlier settlements and gardens north of Al-Qarah, in the area of Jawatha, an important historic settlement of Al-Ahsa Oasis at the dawn of Islam.”

Witness is borne to the historic threat poised to humankind’s dogged but always tentative foothold on existence in the desert oasis by excavations at the Jawatha archaeological site to the north of the Eastern Oasis.

Today, the site is covered entirely with sand, beneath which evidence has been found of ancient agricultural activity, irrigation techniques, long-lost settlements and the course of a vanished river.

Pottery finds from the Ubaid period, dating back roughly 7,000 years, also suggest the Al-Ahsa region may have been among the first in eastern Arabia to have been settled by humans.

Other pottery remains discovered at the site, from Dilmun shards dating from about 2,700 years ago and Greek and Roman ceramics to early Islamic pottery, testify to Al-Ahsa’s long and profitable existence as a major trading center.

Even in antiquity, as the UNESCO nomination document notes, Al-Ahsa was known as “the most famous and largest oasis in the world,” celebrated by Greek, Roman and medieval Arab scholars and travelers.

According to “Geographica,” an account of the then-known world by the Greek historian Strabo published in 7 B.C., ancient Al-Ahsa was connected to Mesopotamia — modern-day Iraq — by trade in spices, aromatics and dates. The inhabitants, he wrote, carried their cargoes “on rafts to Babylonia, and thence sail up the Euphrates with them, and then convey them by land to all parts of the country.”

Alive and well today, thanks to large-scale anti-desertification initiatives and the re-organization of water distribution techniques, including the creation of a new network of canals since the late 1960s, Al-Ahsa is living history.

In the words of the nomination document that won Al-Ahsa recognition as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, the ongoing story of the evolution of the oasis, whose origins coincide with the very beginnings of agriculture, “explains how very ancient human communities were born and worked, and it enables us to understand the techniques, procedures and principles permitting the establishment of harmonious and balanced relationships between human presence and land management.”

Al-Ahsa continues to supply dates to a global market. But perhaps its most valuable fruit is the example set for both the present and the future by its thousands of years of stubborn and ingenious existence in the face of great environmental odds.

Today, in the words of the UNESCO citation, “all over the planet entire ecosystems are at risk of collapse. Oases can show us how to better handle the interaction with the environment by improving its resources without depleting them. Climate change, the collapse of ecosystems, cataclysms, the end of civilization, are conditions that the people of the desert have already faced many times.”

Al-Ahsa, it says, “is an extraordinary example of evolution through time of an oasis landscape,” and one that has invaluable lessons for life on earth — and beyond.

The techniques honed over centuries, “for the creation of fertile soils — for agricultural production, water management, recycling, energy saving, survival in the desert — constitute an example of good practices for the entire planet, providing knowledge applicable to the new frontiers of human diffusion to extreme environment — including extraterrestrial ones.”

An aerial view of part of the oasis taken in 1965. (Saudi Aramco)

An aerial view of part of the oasis taken in 1965. (Saudi Aramco)

Sketches from the notebook of Panaiotis Kruklidis, an Italian architect who helped to prepare the document nominating Al-Ahsa as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Sketches from the notebook of Panaiotis Kruklidis, an Italian architect who helped to prepare the document nominating Al-Ahsa as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The palm groves at Al-Ahsa are, according to the UNESCO nomination document, “among the largest at the global scale.” They also preserve the historical characterstics of systems based on “traditional techniques remained unchanged...for thousands of years.” (Saudi Ministry of Tourism)

The palm groves at Al-Ahsa are, according to the UNESCO nomination document, “among the largest at the global scale.” They also preserve the historical characterstics of systems based on “traditional techniques remained unchanged...for thousands of years.” (Saudi Ministry of Tourism)

A bustling marketplace at Al-Ahsa Oasis, captured in this 1937 photograph by Geraldine Rendel, the wife of a British diplomat and the first European woman to be received in public by Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia. (Middle East Center Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford)

A bustling marketplace at Al-Ahsa Oasis, captured in this 1937 photograph by Geraldine Rendel, the wife of a British diplomat and the first European woman to be received in public by Ibn Saud, the founder of Saudi Arabia. (Middle East Center Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford)

A series of renderings by the Italian architect and heritage expert Panaiotis Kruklidis shows the transformation of the Arabian landscape and the oasis of Al-Ahsa from the Neolithic age, over 4,000 years ago, to the Bronze Age ...

... through the Hellenistic Age ...

... and the Middle Ages ...

... to modern times.

Historic Jeddah:

Gateway to Makkah

The old beating heart of a modern city

In April 2020, London rare-books dealer Peter Harrington offered for sale a collection of engineering plans that told the story of the modernization of Jeddah’s water supply, a long-overdue upgrade to a creaking Ottoman system ordered in 1947 by Ibn Saud to improve the quality of life for pilgrims arriving in the city.

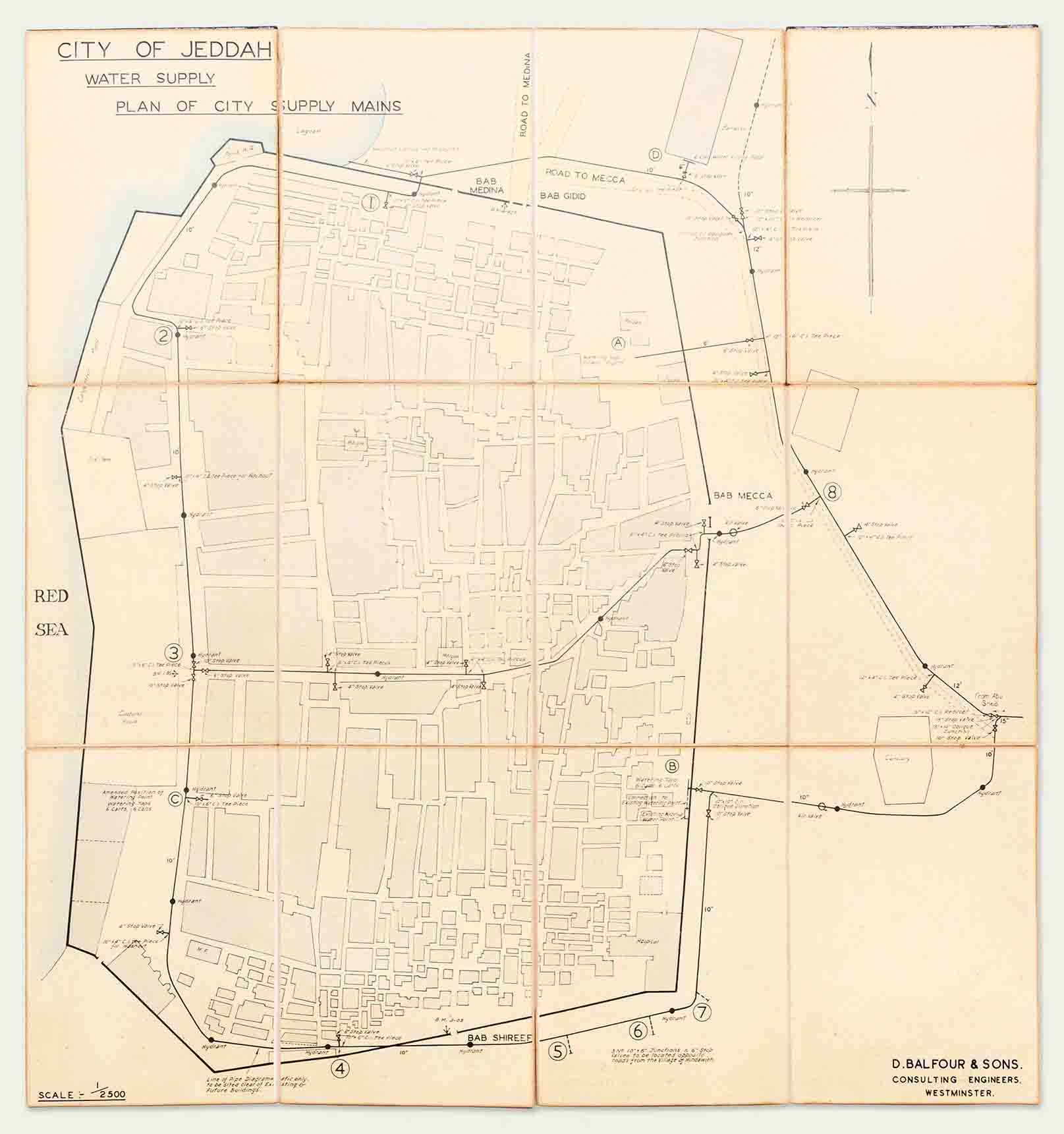

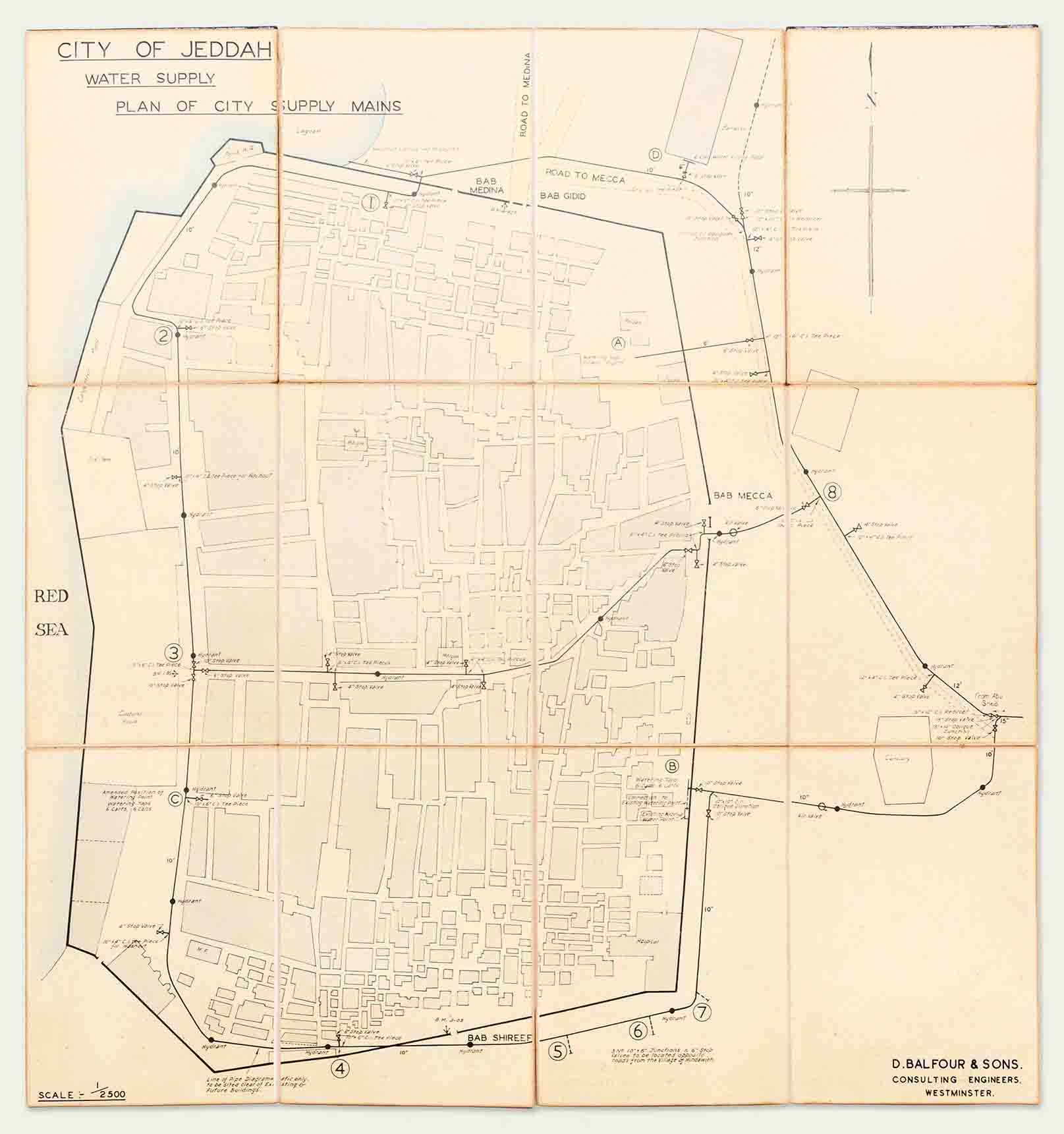

Among the papers was a map made by the British engineering company Balfour & Sons, which had been contracted to carry out the work. The map had been drawn up for the everyday purpose of recording the routes of the newly laid water mains.

This 1947 map, a technical record of Jeddah's newly installed water system, shows the layout of the old town shortly before its walls were torn down to make way for the city's rapid expansion. (Peter Harrington Rare Books, London)

But today, as the last known illustration of the layout of the old city of Jeddah, complete with the great defensive wall that once encircled it, the map has acquired the status of a rare and historically priceless artifact.

Within months of the completion of the drawing, work had begun on the demolition of the old wall, parts of which dated back to the 16th century, and the four gates that had controlled access to the city through hundreds of years of turbulent history.

By 1947, in addition to benefiting from an increase in the number of pilgrims following the end of the Second World War, Saudi Arabia was in the grip of its first great oil boom. Jeddah, since 647 the gateway port to Makkah and always an important town for seaborne trade on the Red Sea, was thriving and expanding rapidly.

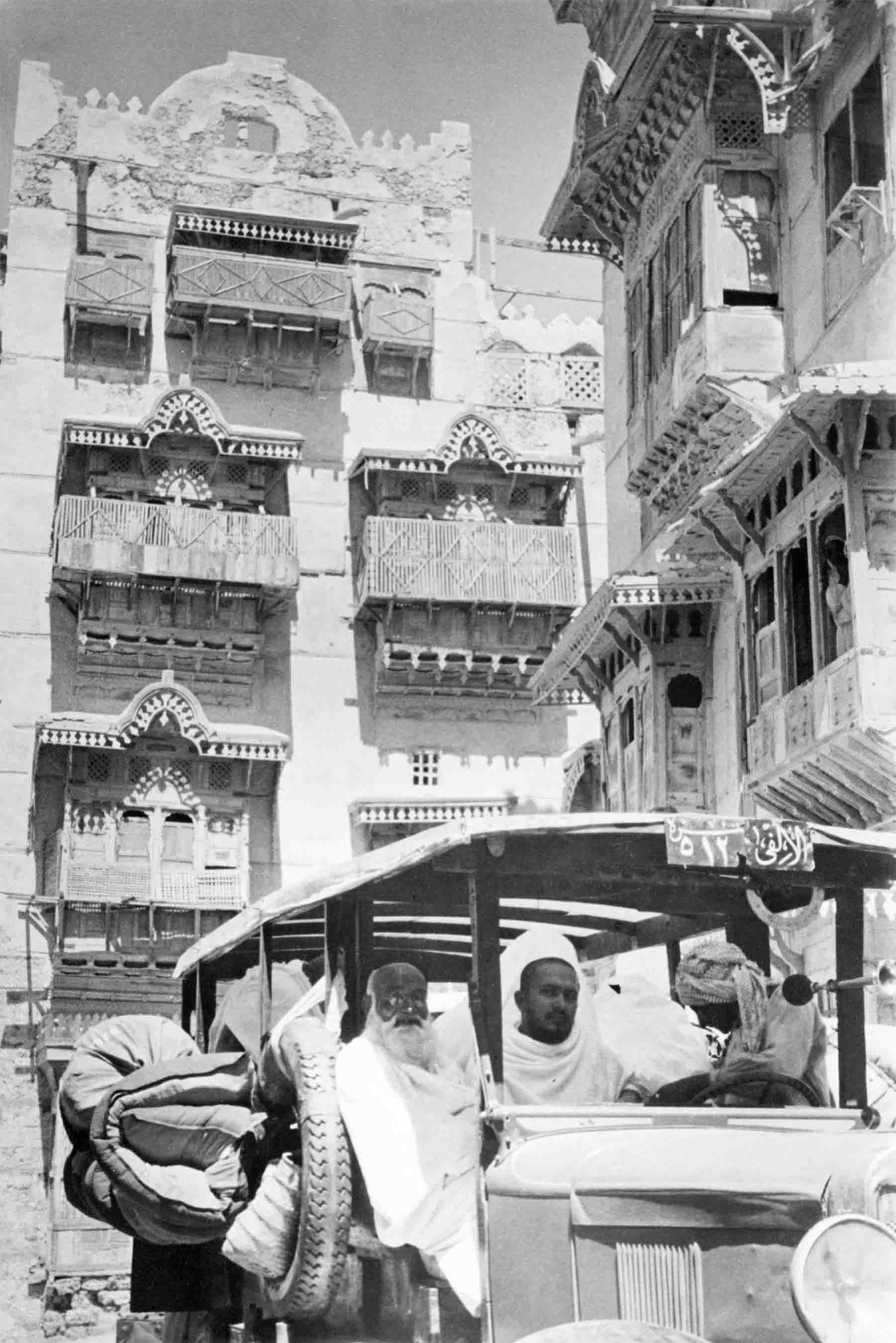

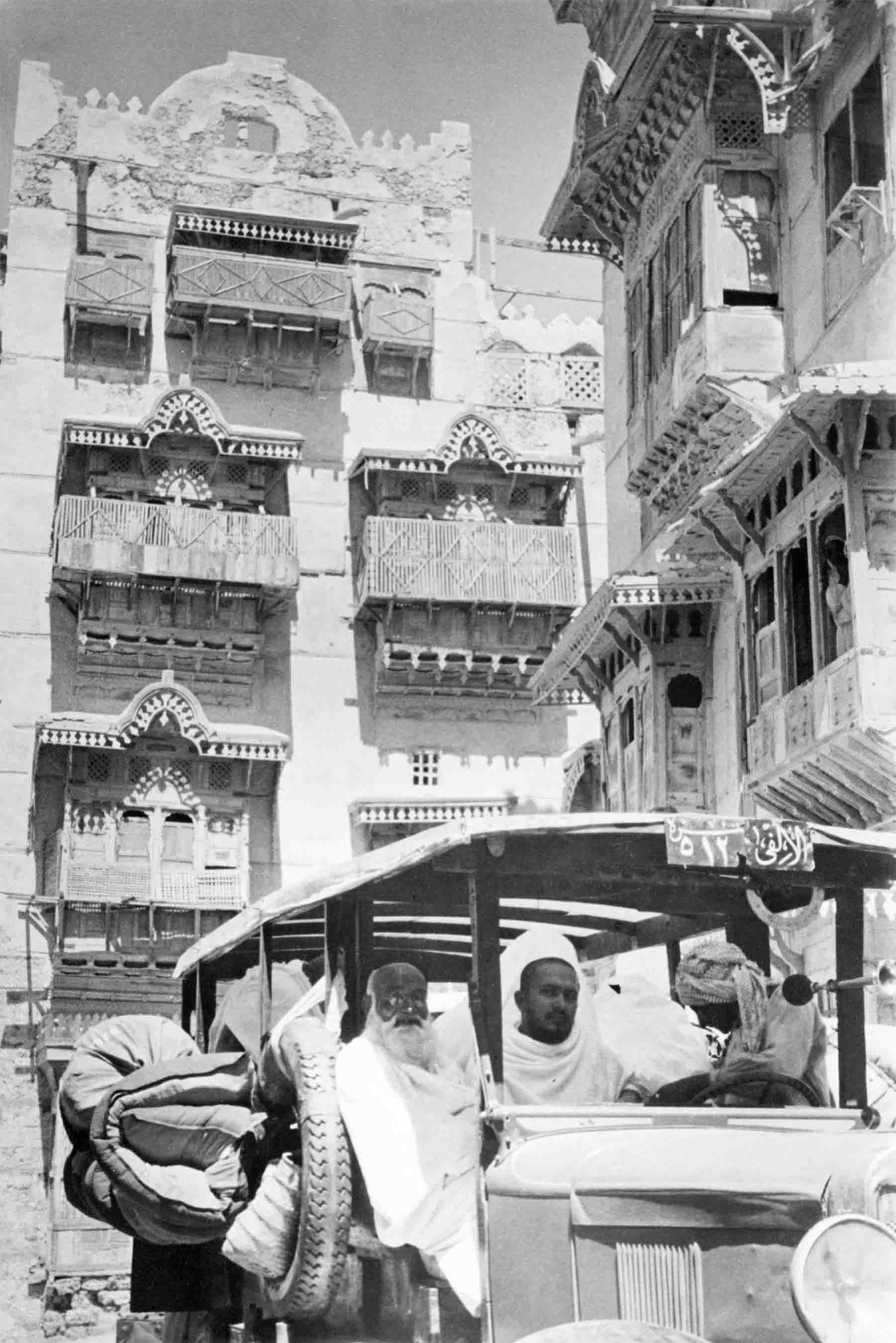

A service station in Jeddah in 1952. By then Saudi Arabia was in the grip of the oil boom that would transform the Red Sea port and the entire country. (Getty Images)

“Until 1947, Jeddah was still surrounded by its wall, and it was a really small place, less than one square kilometer, with a few suburbs in the south,” said architect Simone Ricca, a heritage conservation expert who helped to prepare Saudi Arabia’s successful application to have the city listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

“It was a seasonal city, living through the arrival of pilgrims, many of whom would stay a few months in the city. Because of that, houses were built with floors that were rented out to pilgrims, and this helped create the special architecture we see today in the old town.”

By 1956, with the flow of oil money funding modernization and expansion programs across the country, Jeddah had burst its bounds and, in under 10 years, had swollen to 10 times its size a decade earlier.

By the end of the 1970s, Jeddah Islamic Port had been built on reclaimed land, cutting off the old town from the sea, and the population of the city had risen to close to 1 million.

But despite Jeddah’s rapid expansion, thanks to the dedication of many individuals and organizations determined to conserve the historic heart of the city known fondly to Jeddawis as Al-Balad, the old town somehow managed to survive. In 2014, it became the third historic site in Saudi Arabia to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List as a site of “outstanding universal value.”

Jeddah has been linked inextricably with the Hajj ever since 647, when Uthman ibn Affan, a companion of the Prophet and the third Rashidun caliph, designated it as the gateway port for pilgrims traveling to the holy cities of Makkah and Madinah.

For hundreds of years, pilgrims bound for Makkah arrived in ships that anchored off Jeddah’s shallow harbor, putting ashore in small wooden dhows, or sambouks, to seek lodgings, food and supplies in the houses and souqs lining its narrow, bustling streets. When the time came, they set off on foot or on camel to travel the 70 kilometers to the holy city.

The original Bab Makkah, the eastern gate through which generations of Muslims passed at the start of their spiritual journey of a lifetime, is no more. But as though still protected by the long-vanished walls behind which they once stood, the streets, souqs and buildings of the old town preserve the memory of a vanished way of life even as they echo with the vibrancy of the modern city that surrounds them.

Urban archaeologists believe that the layout of the old town, and perhaps even the architectural style of Jeddah’s buildings, probably date to at least the 16th century, but Jeddah’s origins can be traced back much further. Archaeological finds in the area, including ancient inscriptions in wadis east of Jeddah, suggest it may have been occupied since the late Stone Age, more than 3,000 years ago.

Minarets rise above the city walls of Jeddah in this engraving of the city, published in 1851. (Getty Images)

Thanks to its roles as both a major trading center and as the gateway to Makkah, Jeddah became a melting pot, influenced by the customs, food, skills and products brought by traders and pilgrims from across Africa and Asia, many of whom chose to settle in the town.

In the words of the UNESCO nomination document, the result was “a unique cultural ensemble,” and the surviving cityscape of Historic Jeddah is the product of “an important exchange of human values, technical know-how, building materials and techniques across the Red Sea region and along the Indian Ocean routes between the 16th and the early 20th centuries.”

As such, it represents “a cultural world that thrived thanks to international sea trade, possessed a shared geographical, cultural and religious background, and built settlements with specific and innovative technical and aesthetic solutions to cope with the extreme climatic conditions of the region.”

Always the most important, largest and richest of the Red Sea settlements, today Jeddah’s old town is the last surviving example of an otherwise vanished social and architectural urban style, “an extraordinary pre-modern urban environment where isolated tower houses, lower coral stone houses, mosques, ribats, souks and small public squares compose a vibrant space, inhabited by a multicultural population, that still plays a major symbolic and economic role in the life of the modern metropolis.”

The most distinctive manifestations of that style are the roshan tower houses, some 300 of which survive. A product of economic and environmental circumstances, this style of architecture began to emerge during the second half of the 19th century as a direct by-product of the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869, which boosted Jeddah’s role as an important port linking East and West.

Two of the roshan tower houses that are unique to Old Jeddah can be seen in this 1939 photograph. (Getty Images)

As Jeddah’s merchants grew more and more prosperous, they built higher and more elaborately decorated houses reflecting their new position and wealth. Some houses reached as high as six or even seven stories. Built tall to capture breezes wafting in from the sea, the stairwell or lightwell at the center of many houses, left open to the sky, was designed as a ventilation shaft that allowed hot air to escape upward, increasing airflow inside the building.

“During the hot summer months, residents of a traditional Jeddawi home would sleep in the mabeet, the sleeping quarters on the top floor of the home, with large windows and slits to allow good ventilation,” said Ahmed Badeeb, a resident of Jeddah and a conservationist who was part of the Saudi team that successfully presented Jeddah’s case at the 38th session of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee in Qatar in 2014.

Jeddawi Ahmed Badeeb takes us on a tour of Harat Al-Mazloom.

Old Jeddah’s homes, he said, were built from locally available and imported materials and were “designed and engineered in a manner that would ensure longevity and handle the climate.” Coral limestone was taken from the nearby Red Sea reefs and then crushed and mixed with mud or clay from lake beds to create bricks.

The finished buildings were then whitewashed using an insulating substance Jeddawis called al-norah, made from heated limestone mixed with mud, which helped to keep the insides of buildings cool during the blisteringly hot summer months.

The traditional Jeddawi home, Badeeb said, “was constructed around one large main base pillar known as fahl al-daraj, around which the stairs would be built, with rooms off to the sides.

“Each level was designed according to its function. At the entrance of the home, the diwan was where guests were received and was designated specifically for men. The back area of the house was where the women of the household, children and help usually stayed.”

Many homes had a majlis, “an area similar to the diwan but located on the second floor, with wooden seating areas and pillows pushed toward the walls and the large roshan window at the far wall overlooking the outside streets and alleys.”

The rawasheen (plural of roshan), elaborate wooden bay windows that front many of the surviving houses, served several roles, creating a cool and private place for sitting and sleeping and a sanctuary where women could watch the world outside without being seen from the street. The design of the roshan was so effective at creating cross-ventilation that clay water pots were placed in them to be cooled in the shade and the airflow they created.

Tower houses, with their original elaborate screened bay windows, or rawasheen, are among the most striking features of Jeddah's historic quarter. (Shutterstock)

“It’s difficult to pinpoint where the roshan originated from, as Jeddah was home to many different cultures,” said Badeeb. “The ventilation system would help keep homes cool during the day, and the intricate designs helped to break up the searing heat of the sun’s rays.

“Residents would also be able to peer out through the holes while ensuring their privacy. People outside weren’t able to see whoever was looking out.”

Thanks to imports of timber, mainly hardwoods from Asia and Africa, wood played a vital part in the evolution of Jeddah’s homes, from the development of the roshan to the use of a technique known as takleel, in which wooden beams were used to strengthen brickwork, allowing some houses to be built up to six or seven stories high.

The use of timber is also evident in the large and beautiful doors that grace many of the old buildings. Originally signs of wealth and prestige, they are made from solid wood, often teak, and decorated with elaborately carved panels acknowledged in the UNESCO nomination as examples of “some of the finest carpentry and decoration in Arabia.”

Elaborately carved wooden doors, made from timber imported from Asia and Africa as Jeddah rose to prominence as a major trading hub, decorated the houses of wealthy merchants in the old city. (Shutterstock)

Jeddah’s listing in 2014 as a World Heritage Site has helped to reinforce the conservation efforts over the years of successive mayors of Jeddah and many individuals who, like Badeeb, were born and raised in Al-Balad and were determined not to let it die.

“When the city grew up out of its walls, it was easier and cheaper to build outside on barren land,” said Simone Ricca. “But the historic families of Jeddah were still very much attached to their old buildings, and so although they moved out, they kept the family mansions and the city retained its active soul, as it does to this day.”

Conserving Old Jeddah has not been an easy task, said Badeeb, whose old family home in the Mazloom quarter is still standing. “It took a lot of effort and time by families who inherited their homes from their fathers and grandfathers. The area was lost for a while as the urban development of Jeddah flourished and turned into the sprawling city it is today and, for a long time, houses were neglected and overrun by expatriates as Jeddah’s families moved out.”

The UNESCO document notes that “until the early 1950s, extended Saudi families and long-established Yemeni, Indian and East Asia trading families inhabited the old city houses. Following Jeddah’s spectacular growth prompted by increasing pilgrims and oil revenues, the local residents left their traditional abodes to move to newly built suburbs.”

The old city houses, it added, were now “mainly occupied by a high proportion of single, male foreign workers who rent a room, or part of a room, from Saudi landlords.”

Badeeb attributes the saving of old Jeddah in part to conservation initiatives launched by a series of governors of the province of Makkah, started by Prince Majed bin Abdul Aziz and continued by his successors Prince Abdul Majeed bin Abdul Aziz and Prince Khalid Al-Faisal, the current governor, supported by some of Old Jeddah’s families.

Ricca also highlights “the choices made by the mayor of Jeddah, Dr. Mohammed Said Farsi, who while developing a modern city also decided partially to preserve part of the old city.”

A trained architect who became mayor in 1972, Farsi oversaw a five-fold growth in the city’s population by the mid-1980s and was widely known as the father of modern Jeddah. It was, as an obituary published upon his death in 2019 noted, “remarkable that in the midst of creating much-needed infrastructure, Dr. Farsi found time to create a city that was as beautiful as it was functional, with a carefully preserved historic centre.”

This 1947 map, a technical record of Jeddah's newly installed water system, shows the layout of the old town shortly before its walls were torn down to make way for the city's rapid expansion. (Peter Harrington Rare Books, London)

This 1947 map, a technical record of Jeddah's newly installed water system, shows the layout of the old town shortly before its walls were torn down to make way for the city's rapid expansion. (Peter Harrington Rare Books, London)

A service station in Jeddah in 1952. By then Saudi Arabia was in the grip of the oil boom that would transform the Red Sea port and the entire country. (Getty Images)

A service station in Jeddah in 1952. By then Saudi Arabia was in the grip of the oil boom that would transform the Red Sea port and the entire country. (Getty Images)

Minarets rise above the city walls of Jeddah in this engraving of the city, published in 1851. (Getty Images)

Minarets rise above the city walls of Jeddah in this engraving of the city, published in 1851. (Getty Images)

Two of the roshan tower houses that are unique to Old Jeddah can be seen in this 1939 photograph. (Getty Images)

Two of the roshan tower houses that are unique to Old Jeddah can be seen in this 1939 photograph. (Getty Images)

Tower houses, with their original elaborate screened bay windows, or rawasheen, are among the most striking features of Jeddah's historic quarter. (Shutterstock)

Tower houses, with their original elaborate screened bay windows, or rawasheen, are among the most striking features of Jeddah's historic quarter. (Shutterstock)

Elaborately carved wooden doors, made from timber imported from Asia and Africa as Jeddah rose to prominence as a major trading hub, decorated the houses of wealthy merchants in the old city. (Shutterstock)

Elaborately carved wooden doors, made from timber imported from Asia and Africa as Jeddah rose to prominence as a major trading hub, decorated the houses of wealthy merchants in the old city. (Shutterstock)

Diriyah: At-Turaif

Birthplace of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

Nestling in a bend of the Wadi Hanifa, just 10 kilometers northwest of the mighty Kingdom Center tower at the heart of the bustling modern metropolis of Riyadh, can be found the remains of an earlier capital.

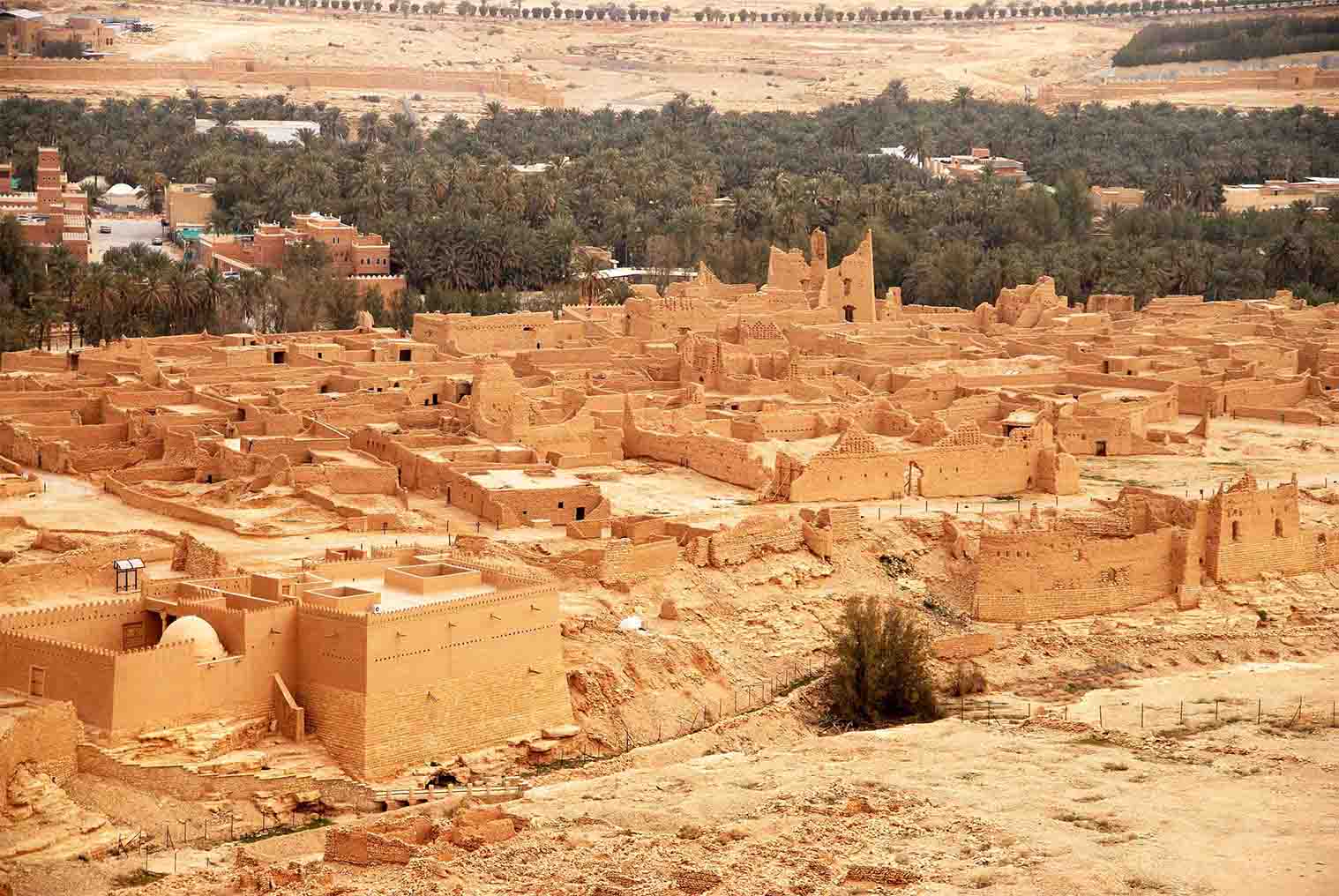

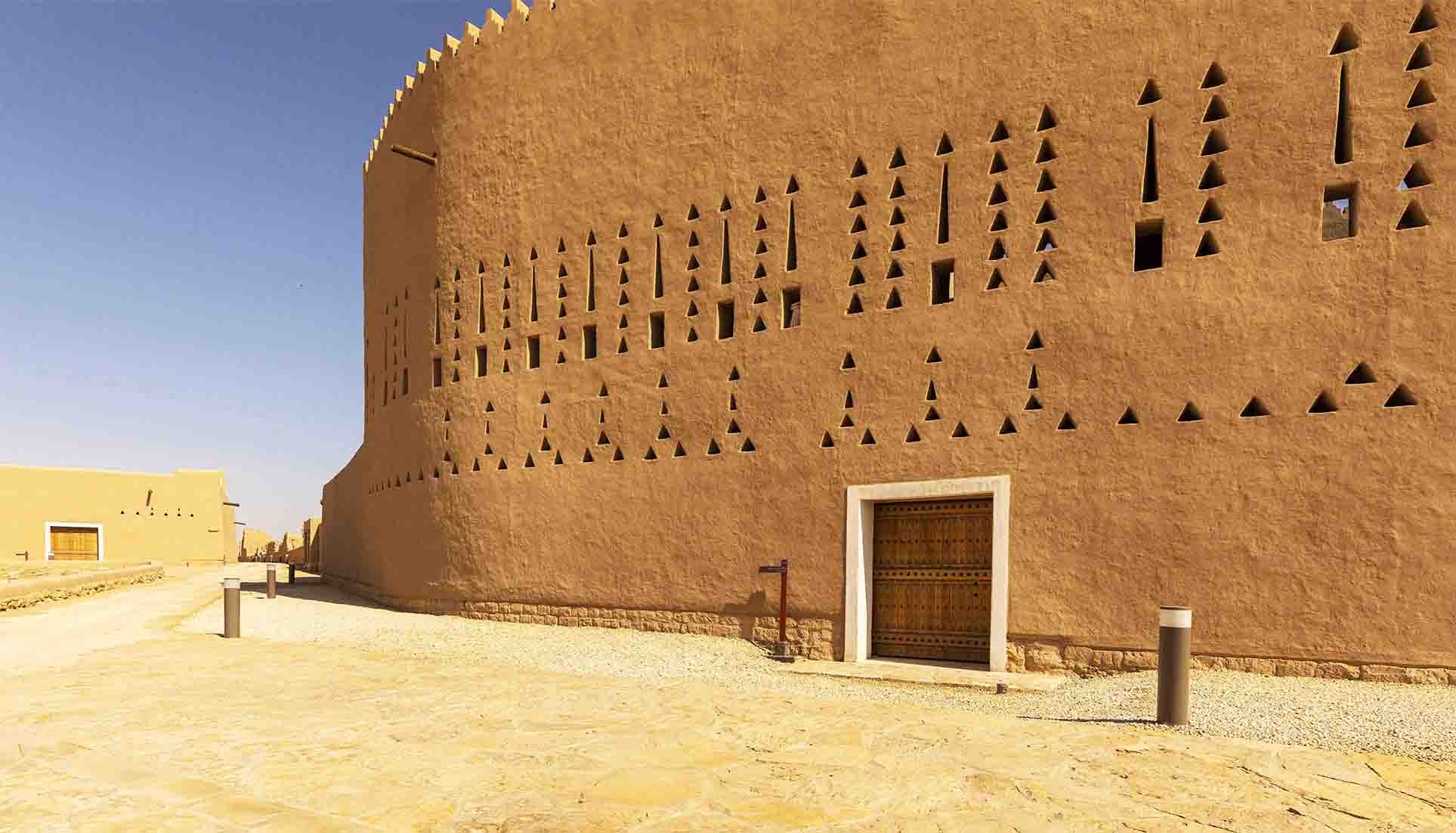

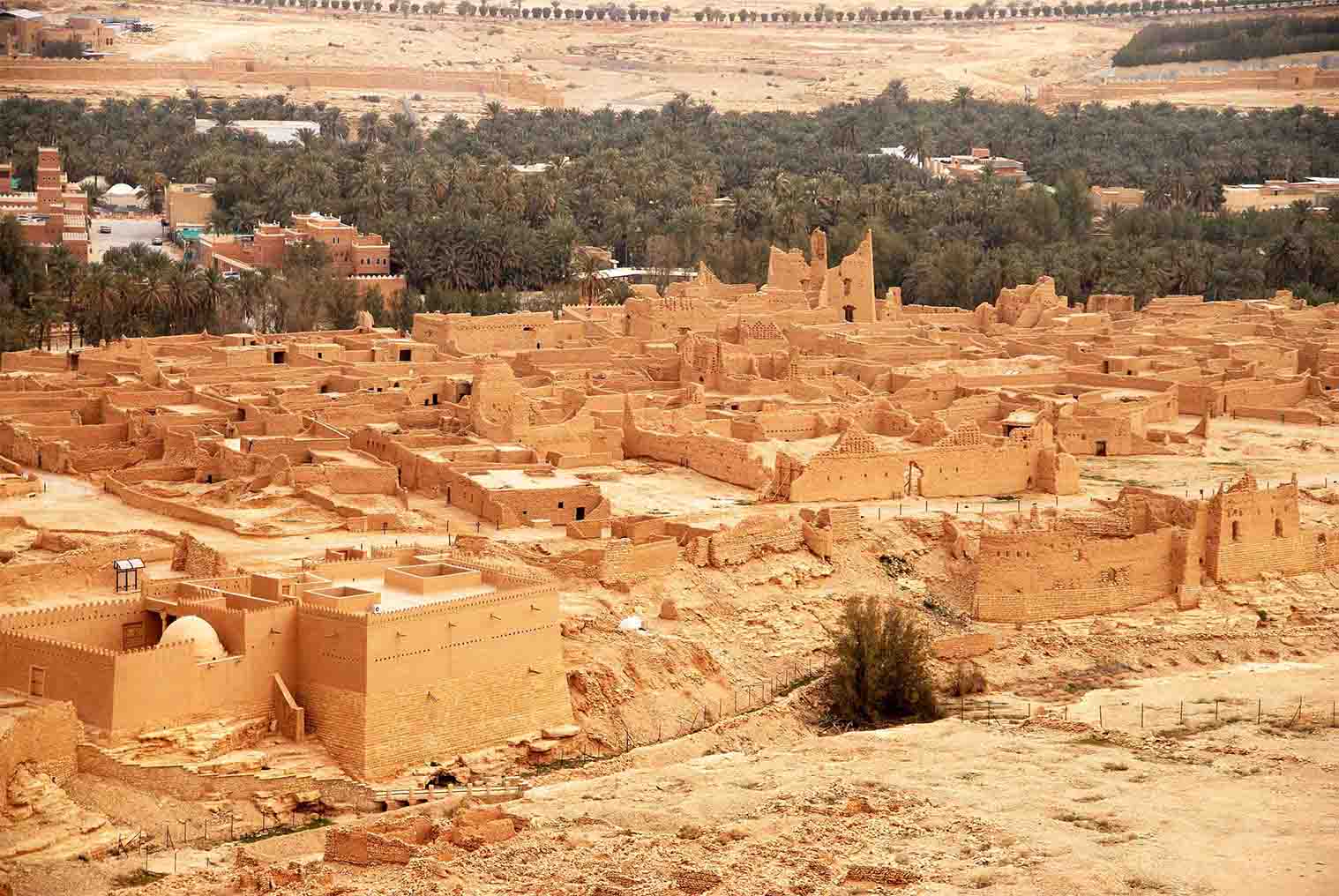

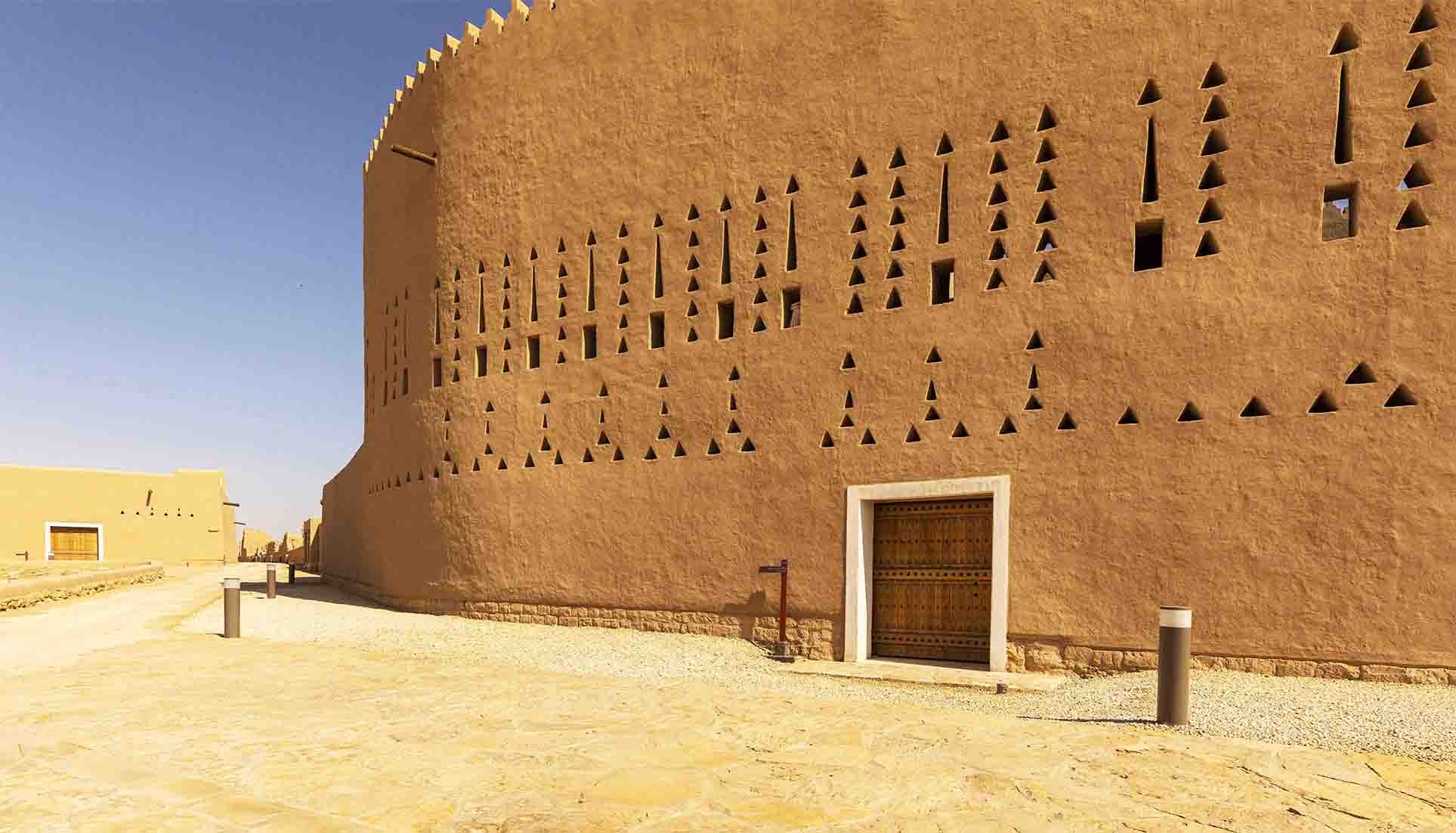

This is At-Turaif, a breathtaking collection of mudbrick palaces, houses and mosques, encircled by a mighty wall, which in the 18th century became the beating heart of the First Saudi State, established in the oasis of Diriyah in 1744.

Together, in the words of the UNESCO nomination that saw At-Turaif inscribed on the World Heritage List in 2010, these constitute “the pre-eminent example of Najdi architectural style, a significant constructive tradition that developed in central Arabia … and contribute to the world’s cultural diversity.”

Diriyah itself, offering fertile land and plentiful water supplies, had been settled in 1446 by forebears of the House of Saud. When they migrated to the Wadi Hanifa from their original settlement at Diriyah, near modern-day Qatif on the Gulf coast, they brought the name of their old home with them.

The mudbrick district of At-Turaif bears the scars of Diriyah's heroic but ultimately doomed six-month resistance against Ottoman forces in 1818. (Historical Diriyah Development Program)

Today, some of the buildings at At-Turaif, bearing the scars of a proud but ultimately doomed stand against the might of the Ottoman war machine in 1818, are in ruins.

Others, including Salwa Palace, the home and seat of government of the third Imam of Diriyah, Saud Al-Kabir (or Saud the Great), on which work began in 1750, are sufficiently intact to remain imposing.

The entire site, however, recognized by UNESCO as being of “outstanding universal value,” is precious to the Saudi people, not only as the birthplace of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia,but also as a symbol of the rise and triumph of the house of Al-Saud over seemingly impossible odds.

At-Turaif did not simply fall into disrepair, a victim of neglect or changing fashions. This is a ghost city, battered and blasted by Ottoman cannon during a heroic siege of Diriyah in 1818 that ended in a wholesale massacre.

During the siege, captured defenders were beheaded and their heads, or sometimes just their ears, were sent back to Cairo for bounty.

When Diriyah finally fell after a valiant six-month defense, many Saudis were exiled, tortured and executed on the orders of Ibrahim Pasha, the Egyptian general who had led his forces in a two-year campaign against the Saudis at the bidding of the Ottomans.

Imam Abdullah, the last ruler of the First Saudi State, who surrendered At-Turaif to the Egyptian only when the suffering of his people had become too much for him to bear, was taken in chains to Constantinople, where he was executed.

Before they withdrew from Najd, the Egyptians laid waste to Diriyah, destroying buildings and fortifications and cutting down every date palm. In 1819, the town was visited by a British army officer, who reported that “it is now in ruins, and the inhabitants who were spared, or escaped from the slaughter, have principally sought shelter in Riyadh.”

Badran Al-Honaihen takes us on an exclusive walk around At-Turaif and shows us what makes its architecture unique and sustainable.

Within months of the Egyptians’ withdrawal, Saudi survivors began to rebuild the city, but in 1821 it was destroyed for a second time by another Ottoman expedition to the area.

Undeterred, the Saudis rose again, this time under the leadership of Imam Turki bin Abdullah Al-Saud. In 1823, he drove out the Ottomans and, with Diriyah and At-Turaif in ruins, chose the nearby intact garrison town of Riyadh as the capital of the Second Saudi State.

Saudi Arabia’s path to statehood was still strewn with barriers. In 1834, Imam Turki was assassinated and years of civil war ended only when his son, Faisal bin Turki bin Abdullah, returned from captivity in Egypt and restored Saudi authority. Following his death in 1865, however, the state was once again riven by in-fighting, until in 1891 it was overthrown by the rival Rashidi dynasty.

Among the Saudis who sought refuge in Kuwait was a young boy, aged about 16. Abdul Aziz bin Abdul Rahman bin Faisal Al-Saud, the son of the exiled ruler of Riyadh, was destined to become better known to the world as Ibn Saud.

The story of how he led a small band of warriors to recapture Riyadh in 1902, restoring the House of Saud, was told by Gertrude Bell, the British political officer in Iraq, in a report written for London in 1917.

A photograph of the ruins of At-Turaif taken in 1917 by the British agent Harry St John Bridger Philby, who settled in Jeddah and became an advisor to Ibn Saud. (Diriyah Gate Development Authority)

“With a force of some eighty camel riders supplied by Kuwait,” she wrote, “Abdul Aziz swooped down upon Riyadh, surprised Rashid’s garrison, slew his representative and proclaimed his own accession from the recaptured city.”

So was the modern state of Saudi Arabia conceived. It would not be an easy gestation.

Ibn Saud and the growing band of Bedouin tribes that began flocking to his banner repelled a series of attacks on his territory, first by Ottoman forces and then by the Hashemites of the Hejaz.

Gradually, though, Ibn Saud expanded the territory under his control, until in 1924 his forces seized Makkah, driving out the Hashemite Sharif Hussain. Ibn Saud united the kingdoms of Najd and Hejaz as one, and on Sept. 23, 1932, proclaimed the foundation of the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

As the capital of the new Saudi state, Riyadh thrived. During the 1970s, Diriyah would rise again, as a new city on the outskirts of the metropolis, but after 1818 the royal quarter of At-Turaif, abandoned behind the remains of its shattered walls, was never occupied again.

For UNESCO, At-Turaif is blessed with many attributes that justify its recognition of “outstanding universal value,” among them the remains of a large number of palaces, built at different times by successive rulers.

Several buildings and the city wall have been restored, to give some idea of how the entire site might have looked during its imposing heyday.

The protected historic quarter of At-Turaif is at the heart of a project to transform Diriyah into a global cultural destination celebrating the birthplace of Saudi Arabia. (Historical Diriyah Development Program)

The site as a whole, unified by the striking colors and textures of the clay and limestone building materials obtained from the bed of Wadi Hanifa, reinforced with timber from the tamarisk tree, “is an urban and architectural monument presenting the culture and lifestyle of the First Saudi State, direct ancestor of the modern Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.”

“The number of palaces that have been discovered until now in At-Turaif district is 13,” said Badran Al-Honaihen, the site’s culture and heritage manager.

“Most of the palaces belonged to members of the royal family during the First Saudi State. Three imams lived in Salwa Palace, which is the most important palace in the center of the district, over 10,000 square meters and overlooking a beautiful view of Wadi Hanifa.”

Architectural details unique to Saudi Arabia's Najd region can be seen on the carefully conserved walls of Prince Saad bin Saud Palace. (Diriyah Gate Development Authority)

Salwa Palace, a complex of seven buildings on which work began in about 1750, is the largest palace in the entire Najd region. Alongside it can be seen the remains of the Bait Al-Mal, the state treasury, built between 1803 and 1814 during the reign of Saud Al-Kabir.

At-Turaif, added Al-Honaihen, is also home to Imam Mohammed bin Saud’s mosque. “The imams of the First Saudi State used to pray there, and it was the scene of many political incidents during that period.” It was also one of the most important mosques in the region, and at one point “the number of worshipers who used to go there exceeded 3,000, which shows how large the First Saudi State was during its glory days.”

In its time, the mosque was also “one of the most important schools of knowledge and education, with lessons in jurisprudence, Shariah and calligraphy.”

Maintaining such buildings, made from mudbricks and susceptible to erosion by rain, is an ongoing task.

“The mudbrick buildings of At-Turaif have been there for more than 250 years and have survived erosion, brutal invasion by the Ottoman Empire and many other problems,” said Al-Honaihen.

This, he added, is a lesson in sustainability reliant on materials taken from the local environment, and one that is being learned by the craftsmen being trained “to work with mudbricks and focusing on sustainability, whether by using the stones and soil from the wadi or by using the local plants and trees that were used to create such tall buildings as Salwa Palace.”

The ruins, said architect Simone Ricca, a heritage conservation expert who helped to prepare Saudi Arabia’s successful UNESCO application for At-Turaif, “have been preserved with attention paid to the traditional building techniques.”

Equally important is the damage wrought by the siege of 1818, another tacit reminder of the Kingdom’s heritage. “The site is, of course, important historically as the birthplace of Saudi Arabia,” he added, “but it is also a quite extraordinary mudbrick village,” reflecting a unique architectural style and know-how.

“The height of the facades of the palaces are very impressive, among the highest mudbrick structures we have. As such they convey the capacity of these materials to create architecture that represented power.

Unique architectural details found throughout At-Turaif include triangular ventilation openings, part of an ingenious early air-conditioning system designed to create airflow and lower temperatures inside the buildings. (Diriyah Gate Development Authority)