Soleimani’s shadow

Qassem Soleimani left a trail of death and destruction in his wake as head of Iran’s Quds Force … until his assassination on Jan. 3, 2020. Yet still, his legacy of murderous interference continues to haunt the region

At around 1 a.m. on Friday, Jan. 3, 2020, a convoy of two vehicles leaving Baghdad International Airport was hit by a salvo of Hellfire missiles from a US MQ-9 Reaper drone. Ten men were killed, including the intended target of the attack, Major General Qassem Soleimani, the 62-year-old commander of the Quds Force, the special-operations branch of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC).

Although Soleimani was widely known to have been responsible for countless deaths through the actions of the proxy militias he supported in Iraq, Afghanistan, Yemen, Syria, Lebanon and Palestine, the overt assassination by the US of a man widely regarded as second in command to Iran’s Supreme Leader sent shockwaves through the global diplomatic community.

Some, both within the US and in other countries, felt the Trump administration had gone too far, breaching an unwritten international code barring the assassination of the members of foreign governments — an act that is anyway specifically forbidden in US law. Inevitably Tehran, which condemned the killing as “an extremely dangerous and foolish escalation,” threatened revenge.

To many commentators, the outbreak of war between the US and Iran seemed highly probable on the eve of Soleimani’s killing. After he was killed, it seemed almost inevitable.

At the time, the region was in the grip of an increasingly dangerous standoff, the origins of which lay in the Trump administration’s decision in May 2018 to withdraw from the internationally agreed Iran nuclear deal. To many commentators, the outbreak of war between the US and Iran seemed highly probable on the eve of Soleimani’s killing. After he was killed, it seemed almost inevitable.

But the rampage of revenge promised by Tehran in response to Soleimani’s death did not materialize.

With the imminent inauguration of a new president in the US, the geopolitical landscape of the region faces fresh upheaval. The incoming Biden administration, seeking to offer Tehran “a credible path back to diplomacy,” seems certain to reinvigorate the Iran nuclear deal.

Governments in the region believe that easing sanctions now would be a terrible mistake that would take economic pressure off Tehran, freeing it to expand its campaign of meddling and to pursue afresh its goal of acquiring nuclear weapons.

Now, one year on from the drone strike that killed Soleimani, Arab News takes a close look at the career of the man who did more than any other to export the discredited spirit of the revolution of 1979 to the wider region and examines the curious circumstances of his death.

Forged in revolution

It is unclear whether the 20-year-old Qassem Soleimani took part in the demonstrations against the rule of the shah that began on the streets of Iran in October 1977. But within two years, Soleimani, born the son of a poor farmer from Iran’s southern Kerman province on March 11, 1957, had found his calling in the service of the revolution that would reshape the geopolitical landscape of the Middle East.

There is no official biography of Soleimani, just glimpses of a life lived largely in the shadows, illuminated only by the occasional carefully controlled public appearance, propaganda issued by the Iranian government and snippets of intelligence.

Seen here in an early undated photograph, Qassem Soleimani was the son of a poor farmer from Iran’s Kerman province. (SalamPix/Abaca/Sipa USA)

By Soleimani’s own account, in a rare autobiographical note unearthed by a scholar at the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research in 2011, he left school in 1970 after completing only five years of primary education. The 13-year-old Soleimani traveled to Kerman city, where he spent the next nine years working in construction and other menial jobs in an attempt to repay the loans his family had taken from the state in a desperate bid to keep their farm afloat.

And then, in 1979, with the toppling of the shah and the return from exile of Ayatollah Khomeini, everything changed.

Soleimani came of age as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, pictured in Tehran shortly after his return from exile on Feb. 5, 1979, toppled the shah. (AFP)

This account of Soleimani’s beginnings was retold just a month before his death, in an article written in December 2019 by General Stanley McChrystal, his former foe as the head of US special operations in Iraq between 2006 and 2008.

“Iran’s deadly puppet master,” wrote McChrystal in Foreign Policy, had “displayed remarkable tenacity at an early age. When his father was unable to pay a debt, the 13-year-old Suleimani worked to pay it off himself.”

As a young man, McChrystal added, Soleimani spent such free time as he had “lifting weights and attending sermons given by a protégé of Iran’s current supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei.”

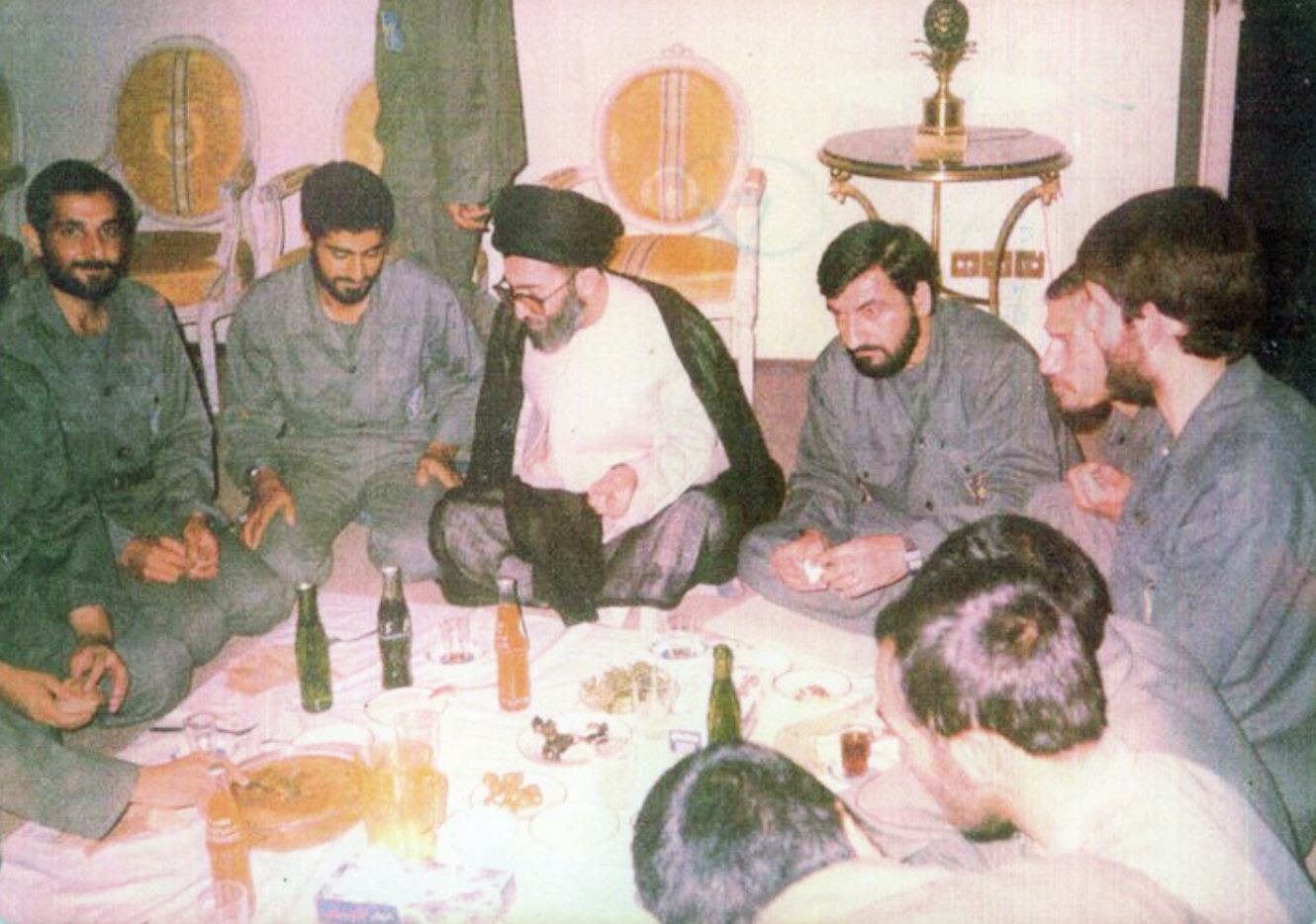

It was that link to Khamenei that some scholars credit with Soleimani’s later promotion within the IRGC to the leadership of its Quds Force. A rare undated photograph taken at some point during the Iran-Iraq War shows Soleimani and a group of fellow fighters sitting down to a meal with Khamenei, who in 1989 would succeed Ayatollah Khomeini as the Supreme Leader of Iran.

Soleimani sits at Khamenei’s right side, at the beginning of a relationship between the two men that would come to have a profound impact on the entire region.

A rare undated photograph taken during the Iran-Iraq War shows Soleimani sitting down to a meal with Ali Khamenei, who in 1989 would succeed Ayatollah Khomeini as Iran’s Supreme Leader.

Soleimani, said Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, an Iranian-American political scientist and a leading expert on foreign policy in Iran and the US, “became the second most powerful man in Iran not just because he was the head of Quds Force, but due to the fact that Ayatollah Ali Khamenei truly viewed Soleimani as a very close friend and confidant.”

Khamenei’s affection for, and absolute trust in, Soleimani was a rare thing.

The Supreme Leader “is known for his suspicion toward other officials, and he sidelined many powerful clergy and politicians after he came to power,” said Rafizadeh. “But he was extremely and personally attached to Soleimani and, as with many dictators, if someone gains their friendship, he or she will be given extra power beyond the law. That is why no other head of the Quds Force or the IRGC has had such power as Soleimani did.”

For his part, wrote McChrystal, Soleimani was “enamored with the Iranian revolution [and] in 1979, at only 22 … began his ascent through the Iranian military, reportedly receiving just six weeks of tactical training before seeing combat for the first time in Iran’s West Azerbaijan province.”

In 1979, Soleimani enrolled in the newly formed Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, better known as the IRGC, which had been set up by Ayatollah Khomeini to defend the revolution. The IRGC’s first challenge, in which Soleimani was blooded, was the rebellion against the new revolutionary regime that broke out in the Kurdish northwest of Iran in March 1979.

At the age of 22, Soleimani enrolled in the newly formed Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, better known as the IRGC. (SalamPix/Abaca/Sipa USA)

At first, wrote political scientist Emanuele Ottolenghi in “The Pasdaran,” his 2011 history of the IRGC, the “ardor and zeal” of the inexperienced guards “proved insufficient to surmount the Kurdish rebellion,” but they persevered.

“As casualties mounted, government forces experienced defeat and desertion, but the Guards … were determined to crush their enemies, whom they considered unbelievers,” wrote Ottolenghi, a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, a Washington think tank. Eventually, “they subjected the rebellion to brutal force, killing some 5,000 Kurdish fighters and as many as 1,200 civilians for sedition and treason.”

Crucially, though, wrote McChrystal, Soleimani was “truly a child of the Iran-Iraq War, which began the next year.”

McChrystal recalled his old foe with a certain grudging respect. Soleimani “emerged from the bloody conflict a hero for the missions he led across Iraq’s border — but more important, he emerged as a confident, proven leader.”

He also emerged with the conviction that post-revolutionary Iran was fighting for its life against all-comers. In a secret report in March 1980, the CIA’s National Foreign Assessment Center put Iran’s determination to export its revolution down in part to ideology — the Iranians saw their revolution as “an example for other ‘oppressed’ peoples” — but the leadership also believed that “if Iran fails to export its revolution, the country will be isolated in an unfriendly environment of hostile regimes.”

Even before the Iran-Iraq War, which saw Saddam Hussein supported by the US, distrust of the West was ingrained in the Iranian psyche. In 1953, Iran’s democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh had been overthrown in a plot, engineered by the CIA and Britain’s MI6, to prevent the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry, then in the hands of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company — later known as BP.

Iran’s distrust of the West dates back to the CIA-engineered coup in August 1953 that toppled Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and restored the monarchy. (AFP)

Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, pictured in a New York hospital in 1951, was overthrown by the Americans and the British to prevent the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry. (AFP)

That coup saw the shah restored to full power, unleashing a program of unpopular reforms, enforced by his brutal secret police, the Savak, that would end in revolution in 1979.

The shah, already sick with terminal cancer, left Iran on Jan. 16, 1979. He travelled to a number of countries before President Jimmy Carter gave him permission to come to the US to undergo surgery in New York in October 1979. Washington rejected Tehran’s demand that the shah be returned to face trial for his alleged crimes, and on Nov. 4 a group of militant students occupied the US embassy in Tehran. The 52 American diplomats and staff they seized were held hostage for 444 days.

Shah Reza Pahlavi and his wife Farah in Marrakech on Jan. 24, 1979, a few days after fleeing the Iranian Revolution. (AFP)

With the hostage crisis, America now had its own cause to harbor a grudge against Iran. That grudge became embedded in the US psyche with the humiliating failure in April 1980 of an attempt by the American military to rescue the hostages. Operation Eagle Claw ended in disaster when a helicopter crashed into a transport aircraft at a staging post in the Iranian desert, destroying both machines in a fireball that left eight US servicemen dead.

After Washington refused to return the shah to face trial in Iran, militant students occupied the US Embassy in Tehran in November 1979, holding 52 American diplomats and staff hostage for 444 days. (Getty Images)

In its assessment of Iran’s post-revolutionary intentions, published one month before the Operation Eagle Claw debacle, the CIA had concluded that Sunni-ruled, Shiite-majority Iraq was Tehran’s “most promising target for subversion in the Arab world.” But on Sept. 22 that year, any plans Iran may have had for exporting its revolution were put on hold when Saddam launched a surprise attack on his neighbor, triggering a war that would last almost eight years, cost up to a million lives and end in stalemate.

Saddam’s declared intention was to destabilize the new Islamic state, for fear of the revolution spreading to Iraq’s majority-Shiite population and beyond. But the invasion had the opposite effect, uniting Iran’s post-revolutionary factions and rallying Islamists and revolutionaries alike to the defense of their homeland.

Among the leading figures who emerged was Mostafa Chamran, the deputy prime minister of the revolutionary government and its minister of defense. In the years before the revolution, Chamran had studied the techniques of irregular warfare with the Palestinian Fatah movement. Now he put his training to good use, not only helping to form a force of volunteers but also leading them into action himself.

This guerilla unit soon gained a reputation for waging a new type of warfare, “combining revolutionary zeal and unconventional tactics,” in the words of Nader Uskowi, senior fellow at the Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security at the Atlantic Council and a senior policy adviser to the US military’s Central Command.

This unit, as Uskowi noted in his 2019 book “Temperature Rising: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Wars in the Middle East,” was the forerunner of the Quds Force.

Chamran was killed in June 1981, in fighting near the besieged western Iranian border town of Susangerd, “but the way of war he had already unleashed would become the hallmark of the future Quds Force,” wrote Uskowi.

Some reports suggest that during the war, Soleimani was already carrying out clandestine operations...

It would also prove to be a transformative experience for the young leader of an IRGC unit from Kerman, who “had gained a reputation for bravery” during the war that is known in Iran as the Sacred Defense.

Soleimani spent the Iran-Iraq War as commander of the 41st Tharallah Division, which took part in a series of major operations, culminating in the bloody Siege of Basra. This ultimately thwarted attempt by the Iranians to seize the Iraqi port city on the Shatt Al-Arab raged throughout January and February 1987 and, like the war itself, ended in stalemate, at the cost of more than 100,000 lives.

Some reports suggest that during the war, Soleimani was already carrying out clandestine operations, supporting Shiite and Kurdish groups inside Iraq opposed to Saddam.

In an article published on his official website in October 2020, Khamenei praised the response of Iranians from all walks of life who had rallied to the defense of the revolution in 1980 — and then singled out one for special mention.

“In such collective movements,” he wrote, “exceptional talents usually show up. For example, such and such, a young man from a village in such and such an area of the country — for example, a village in Kerman — would go to the city and would join the forces.”

This young man, he added, had become “a human resource created in the war … molded and shaped … during the Sacred Defense Era,” who had gone on to have a “brilliant” career “in the arena of diplomacy, international affairs and the like.”

That young man was Qassem Soleimani, and “the like” at which he would come to excel was the dealing out of death and destruction on an apocalyptic scale.

Seen here in an early undated photograph, Qassem Soleimani was the son of a poor farmer from Iran’s Kerman province. (SalamPix/Abaca/Sipa USA)

Seen here in an early undated photograph, Qassem Soleimani was the son of a poor farmer from Iran’s Kerman province. (SalamPix/Abaca/Sipa USA)

Soleimani came of age as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, pictured in Tehran shortly after his return from exile on Feb. 5, 1979, toppled the shah. (AFP)

Soleimani came of age as Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, pictured in Tehran shortly after his return from exile on Feb. 5, 1979, toppled the shah. (AFP)

A rare undated photograph taken during the Iran-Iraq War shows Soleimani sitting down to a meal with Ali Khamenei, who in 1989 would succeed Ayatollah Khomeini as Iran’s Supreme Leader.

A rare undated photograph taken during the Iran-Iraq War shows Soleimani sitting down to a meal with Ali Khamenei, who in 1989 would succeed Ayatollah Khomeini as Iran’s Supreme Leader.

At the age of 22, Soleimani enrolled in the newly formed Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, better known as the IRGC. (SalamPix/Abaca/Sipa USA)

At the age of 22, Soleimani enrolled in the newly formed Army of the Guardians of the Islamic Revolution, better known as the IRGC. (SalamPix/Abaca/Sipa USA)

Iran’s distrust of the West dates back to the CIA-engineered coup in August 1953 that toppled Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and restored the monarchy. (AFP)

Iran’s distrust of the West dates back to the CIA-engineered coup in August 1953 that toppled Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh and restored the monarchy. (AFP)

Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, pictured in a New York hospital in 1951, was overthrown by the Americans and the British to prevent the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry. (AFP)

Iranian Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh, pictured in a New York hospital in 1951, was overthrown by the Americans and the British to prevent the nationalization of Iran’s oil industry. (AFP)

Shah Reza Pahlavi and his wife Farah in Marrakech on Jan. 24, 1979, a few days after fleeing the Iranian Revolution. (AFP)

Shah Reza Pahlavi and his wife Farah in Marrakech on Jan. 24, 1979, a few days after fleeing the Iranian Revolution. (AFP)

After Washington refused to return the shah to face trial in Iran, militant students occupied the US Embassy in Tehran in November 1979, holding 52 American diplomats and staff hostage for 444 days. (Getty Images)

After Washington refused to return the shah to face trial in Iran, militant students occupied the US Embassy in Tehran in November 1979, holding 52 American diplomats and staff hostage for 444 days. (Getty Images)

See how Qassem Soleimani rose through the ranks of the IRGC amidst times of war and revolution.

Master of mayhem

In 1988, the 41st Tharallah Division returned to Kerman, and from his headquarters there Soleimani spent the best part of the next 10 years combatting the cartels trafficking narcotics into Iran across its porous borders with its chaotic, war-wracked neighbor Afghanistan and, via the turbulent and Sunni-dominated Iranian province of Sistan and Baluchistan, Pakistan.

Ali Alfoneh, a researcher at the American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy, wrote in 2011 that “Soleimani’s campaign claimed many lives but ultimately proved successful.” One Iranian news site Alfoneh cited had reported that “the people of Kerman … still consider the era of the presence of Qassem Soleimani in the eastern and south-eastern parts of the country among the securest.”

Soleimani’s drug-busting activities brought him to the attention of Major General Yahya Rahim Safavi, a senior officer in the IRGC who was appointed head of the guards by Khamenei in September 1997. Shortly after, at the latest by early 1998, Safavi named Soleimani as the new head of the Quds Force, which reports directly to Khamenei.

It is clear from the many photographs released by Iran of Soleimani and the Supreme Leader together over the years that Khamenei and the man he hailed in a speech in May 2005 as “a living martyr” were close.

Frequently photographed together over the years, it was clear that Soleimani and Ayatollah Khameini were close. (Alamy)

Newly in charge of the Quds Force, Soleimani’s first priority was Afghanistan, where Iran’s ideological enemies the Taliban had seized power the year before and, in August 1998, executed 11 Iranian diplomats and a journalist after capturing the northern city of Mazar-i-Sharif. In a show of force in November that year, the Iranian army massed more than 200,000 troops on the Afghan border in the province of Sistan and Baluchistan. Iran, said Brigadier General Ali Shahbazi, the army’s commander-in-chief, was “ready to suppress any kind of plot by the enemies of Iran.”

So too was the IRGC, which sent 70,000 Revolutionary Guards to the region. But in his first major campaign as head of the IRGC’s Quds Force, Soleimani was busy developing what would become his modus operandi — running covert operations in support of proxy groups in enemy territory.

His movements at this time were, by necessity, shrouded in secrecy, but a brief news item published in the Tehran Times in 1999 revealed that Soleimani was working behind the scenes in support of the United Islamic Front for the Salvation of Afghanistan, also known as the Northern Alliance, which sprang up in 1996 to resist the Taliban and was composed mainly of Tajiks.

On Jan. 23, 1999, the paper reported that an “Iranian army delegation” was in Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, “to discuss defense issues with senior Tajik officials” and the “implementation of a defense agreement reached between the two countries.” The Iranian army delegation, added the short report, was headed by one Brigadier General Qassem Soleimani. He was not, of course, part of the army, but the Quds Force would not be officially acknowledged in Iran until the outbreak of the war in Syria in 2011.

Soleimani had embarked on a career that would see him singlehandedly orchestrate and expand the hegemony of Iran over events in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen. In the process, he opened up a land corridor whose route and purpose echoed the achievements of Persia’s King Darius I, ruler of the powerful Achaemenid Empire from 522 to 486 B.C.

The corridor “follows rather closely the path of an ancient land bridge, the Royal Road, which was built by Darius the Great,” wrote Uskowi, an expert on Iranian military strategy, in his 2018 book “Temperature Rising: Iran’s Revolutionary Guards and Wars in the Middle East.”

Darius, he continued, “built the road to facilitate logistics and communications throughout his large empire … Twenty-six centuries later, the Quds Force and its commander, General Qassem Soleimani, have secured a line of communication largely following that ancient route, connecting Iranian-led forces in the western front to their supply base in Iran.” As a result, the Quds Force “can now move personnel and materiel on land from Iran to Syria and Lebanon and the Israeli northern fronts.”

The historic resonance of that achievement is not lost on Sir John Jenkins, the former British ambassador to Iraq and Saudi Arabia. “There hasn’t been an Iranian presence on the Mediterranean since the Achaemenid Empire,” he said. “The last time was about 330 B.C., and now they are back.”

The purpose, he said, is not merely to support Syria because it is Iran’s only state friend in the region, but “because it gives them strategic depth and it gives their economy breathing space.” This, he said, is what Iran is trying to achieve in Iraq, as it has already achieved in Lebanon — “to use Iraq as one of its external economic lungs, by creating a parallel economy.”

Iran was designated by the US as a state sponsor of terrorism in 1993, for its support of organizations including Lebanese Hezbollah, Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad. Thereafter, in the US State Department’s annual report on global terrorism, the country has been consistently described as “the most active state sponsor of terrorism” in the world.

Hezbollah fighters march in Beirut on May 31, 2019, to mark Al-Quds (Jerusalem) International Day, founded by Ayatollah Khomeini. Iran has spent millions of dollars training, arming and funding Hezbollah. (AFP)

But not without irony, it was the chaotic aftermath of the US invasion of Iraq that gave Soleimani the opportunity to open up his land bridge from Iran to the wider region, helping him to develop his network of forces in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.

It is not clear when Soleimani first came to the attention of the Americans, but he certainly did so in the turbulent years following the war in Iraq in 2003.

Tehran, which had always maintained close relations with Iraq’s Shiite community, saw the invasion as an opportunity to transform Iraq into a satellite of Iran. When Saddam’s regime fell, wrote Uskowi, “Quds Force senior officers crossed the porous border into a chaotic Iraq, bringing with them a large contingent of Iraqi exiles who had fought alongside the IRGC against their own country’s military during the Iran-Iraq War of 1980s.”

The newly arrived Iraqis soon began organizing young Shiites and, “before long, the Quds Force and its allied Shia militia groups were staging a bloody war against the U.S. with the goal of pushing their troops out of Iraq.” Their aim was “to establish a Shia-led government modeled on the Iranian experience — an Islamic Republic of Iraq of sorts.”

In the wake of the war, Iran empowered several militia groups that are now main players in the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), the umbrella group of militias founded in 2014 by the Iraqi government. Among those supported by Iran is Kataib Hezbollah, whose leader Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis would die alongside Soleimani in January 2020.

Other groups in Iraq sponsored by the Quds Force include Harakat Al-Nujaba, the Badr Brigade, Asaib Ahl Al-Haq and Kataib Imam Ali.

In April 2019, the Pentagon released figures indicating that during the eight years of Operation Iraqi Freedom, Quds Force-backed militias had been responsible for the deaths of at least 603 US service personnel — 17 percent of all US deaths from 2003 to 2011 — “in addition to the many thousands of Iraqis killed by the IRGC’s proxies.”

By Uskowi’s assessment, by the time the US pulled out in 2011, “the Quds Force-led Iraqi Shia militia forces were by then tens of thousands strong; further, the insurgency had made them well trained, well armed, and battle tested. The government in Baghdad was led by Shias, and the prime minister was especially close to Tehran. Iraq had effectively become a satellite state of Iran.”

For many years, US intelligence reports had given credit for Iran’s terrorist activities to the IRGC in general, but in 2007 Soleimani’s personal profile was raised when both he and the Quds Force were among several individuals and organizations designated by the US Treasury as part of moves “to counter Iran's bid for nuclear capabilities and support for terrorism by exposing Iranian banks, companies and individuals that have been involved in these dangerous activities and by cutting them off from the U.S. financial system.”

In its report for 2009, the US Office of the Coordinator for Counterterrorism recognized that the Quds Force “is the regime’s primary mechanism for cultivating and supporting terrorists abroad.”

The report, published in August 2010, highlighted the extent of Quds Force activities throughout 2009 — providing weapons, training and funding to Hamas and other Palestinian terrorist groups, rearming and providing hundreds of millions of dollars in support of Hezbollah in Lebanon, training thousands of its fighters in camps in Iran and training the Taliban in Afghanistan on small-unit tactics, small arms, explosives and heavy weapons including mortars, artillery, and rockets.

In Iraq, “the Quds Force continued to supply Iraqi militants with Iranian-produced advanced rockets, sniper rifles, automatic weapons, and mortars that have killed Iraqi and Coalition Forces, as well as civilians” and was directly responsible for “the increased lethality of some attacks on U.S. forces by providing militants with the capability to assemble explosives designed to defeat armored vehicles.”

In concert with Lebanese Hezbollah, the Quds Force had “provided training outside of Iraq as well as advisors inside Iraq for Shia militants in the construction and use of sophisticated improvised explosive device technology and other advanced weaponry.”

Soleimani was the driving force behind all this mayhem, yet remarkably his abilities appeared to win the grudging respect of his enemies.

His one-time foe Gen. McChrystal later praised Soleimani’s “quiet cleverness and grit … his brilliance, effectiveness, and commitment to his country.” Friends and enemies alike, wrote McChrystal in the winter of 2019, agreed that “the humble leader’s steady hand has helped guide Iranian foreign policy for decades — and there is no denying his successes on the battlefield.”

Soleimani, he concluded, “is arguably the most powerful and unconstrained actor in the Middle East today. US defense officials have reported that Soleimani is running the Syrian civil war (via Iran’s local proxies) all on his own.”

For Soleimani, the year 2011 began well enough. On Jan. 24, Khamenei promoted his old friend to major general, the highest rank held by anyone in the IRGC since the end of the Iran-Iraq War.

His notoriety grew. In October that year, Soleimani was mentioned in US dispatches once again, when he was one of four named IRGC members designated by the Department of the Treasury for their connection to a failed bomb plot to assassinate Adel Al-Jubeir, then the Saudi ambassador to the US.

But 2011 also ushered in the Arab Spring, which presented Soleimani with problems — and opportunities. As the movement spread, writes Alfoneh, the “Quds Force suddenly found itself defending friendly governments in Damascus, as well as Baghdad, against a growing and increasingly militant Sunni opposition.”

The defense of Assad’s regime nearly cost Soleimani his life. In November 2015, it was reported that he had suffered shrapnel wounds in fighting near Aleppo, but on Dec. 1, Iranian news agency Tasnim dismissed the story. In an “exclusive” interview, the Quds Force commander, “in response to the rumors revolving around his death while laughing said, ‘Martyrdom is what I seek in mountains and valleys but isn’t granted yet’.”

Opportunity presented itself to Soleimani in Yemen, where in 2011 he was in a position to exploit the Shiite Houthi revolution, which in 2015 would draw in a coalition of Arab states led by Saudi Arabia.

The Houthis had always been supporters of the Islamic revolution, and in turn Iran had always supported, trained and armed the Houthis. When the coalition intervened to counter the expansion of yet another Iranian-backed proxy, this time on Saudi Arabia’s doorstep, it faced well-trained, well-armed and ideologically motivated fighters.

Concrete evidence of this was found in January 2013 when the Yemeni coast guard intercepted the Jihan, a vessel found to be carrying a vast cache of Iranian-made arms and related material. The 13 people arrested included two members of Hezbollah and three IRGC agents — all released when the Houthis took over Sanaa in September 2014.

Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces chant before going into battle during the offensive to liberate Mosul from Daesh on Oct. 31, 2016, in Tal Al-Zaqaa, Iraq. (Getty Images)

Shipments of weapons from Iran to Yemen appear to have continued ever since, despite increased maritime vigilance by the Saudi coalition and its allies.

In August 2018, the US guided-missile destroyer USS Jason Dunham intercepted a dhow in the Gulf of Aden found to be carrying a consignment of more than 2,500 AK-47 assault rifles, bound for the Houthis. It was the fifth time arms shipments had been intercepted in the region by coalition warships since 2015, and in each case, the weaponry was traced back to Iran.

In August 2018, the guided-missile destroyer USS Jason Dunham intercepted a skiff en route to Yemen found to be carrying a shipment of illicit weapons from Iran. (Alamy)

Following the Arab Spring uprisings in Syria, however, Soleimani’s gift to the threatened regime of President Bashar Al-Assad amounted to far more than simply weaponry. The Quds Force, writes Uskowi, deployed “tens of thousands” of fighters from Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan to the Syrian battlefields, and “the fall of Aleppo in 2016, fought primarily between the Quds Force-led militants and the Sunni opposition, marked the beginning of the final victory of the regime.”

US sailors on board the USS Jason Dunham take an inventory of a large cache of AK-47 automatic rifles intercepted en route to Yemen in August 2018. (Alamy)

As a result, writes Uskowi, “nearly eight years after the 2011 uprisings, the Assad regime is increasingly dependent on Iran.”

In 2012, the civil war had grown even more complex when the Islamic State in Iraq, an offshoot of Al-Qaeda, spilled over the border and, taking advantage of the chaos, seized territory across Syria and Iraq and renamed itself the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (Daesh).

In a quirk of Iran’s complex politics, Soleimani now found himself and his Quds Force fighting the same enemy as the Americans. In June 2014, Daesh captured Mosul and swept southwards. By June, they had taken Jalula, a mere 30 kilometers from the Iranian border.

The Quds Force “mobilized all its forces to defend Baghdad,” writes Uskowi. “It sent Iraqi Shia militias fighting in Syria back to Iraq and deployed armored and artillery elements of the Iranian regular army, Artesh, to the Iraqi side of the border to stop the advance of ISIS. Eventually the Quds Force-led Shia militias, along with Iraqi and Kurdish security forces and U.S.-led coalition forces, rolled back ISIS and recaptured lost territories.”

But it would, said Phillip Smyth, a senior fellow at the Washington Institute, be a mistake to see Soleimani as an ally in the fight against Daesh. “Many of the greatest victories Soleimani’s militias achieved were to use US support of official Iraqi government units and dominate the newly won territory after it was retaken,” he said. “After they found a place in these zones, they dominated and pushed their anti-Americanism and their own policies.”

Yet in 2017, Soleimani’s reputation, carefully managed with photo ops and personal appearances on battlefields, earned him a place in Time magazine’s list of the world’s 100 Most Influential People, with an appraisal written by former CIA analyst Kenneth Pollack.

“To Middle Eastern Shiites,” he wrote, “he is James Bond, Erwin Rommel and Lady Gaga rolled into one. To the West, he is … responsible for exporting Iran’s Islamic revolution, supporting terrorists, subverting pro-Western governments and waging Iran’s foreign wars.”

To the West, he is ... responsible for exporting Iran's Islamic revolution, supporting terrorists, subverting pro-Western governments and waging Iran's foreign wars.

When the Assad regime faced defeat in 2012, “it was Soleimani who brought in Shi’ite militiamen from Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan to Syria, and then the Russians in 2015. When ISIS overran northern Iraq,” Pollack wrote, using another term for the terror group Daesh, “it was Soleimani who armed the Shi’ite militias and organized the defense of Baghdad, where his proxies had often ambushed U.S. troops.” Soleimani, Pollack added, was “also a master of propaganda, posing selfies from battlefields across the region to convince one and all that he is the master of the Middle Eastern chessboard.”

For Soleimani, victory over Daesh was less about a clash of ideologies and more about keeping open his precious logistical land bridge through Iraq to the Mediterranean.

In Iraq especially, Soleimani’s influence extended far beyond the provision of training, weapons and leadership for proxy militia groups. A secret cable sent to Washington by the US Embassy in Baghdad in November 2009, later leaked, documented the extent to which Iran was “a dominant player in Iraq's electoral politics … using its close ties to Shia, Kurdish, and select Sunni figures to shape the political landscape in favor of a united Shia victory in the January election.”

Soleimani, it added, had been “the point man directing the formulation and implementation of the Iranian government’s Iraq policy, with authority second only to Supreme Leader Khamenei,” since “at least 2003.”

Through his Quds Force officers and proxies in Iraq, Soleimani deployed “the full range of diplomatic, security, intelligence and economic tools to influence Iraqi allies and detractors in order to shape a more pro-Iran regime in Baghdad and the provinces.”

Increasingly, Soleimani trod a path that veered between the “pure” guerrilla leadership that had cast his shadow over an entire region and a role as a diplomat to whom enemies and allies alike turned for an understanding of Iran’s aims.

In July 2015, it was Soleimani who flew to Moscow, reportedly at Vladimir Putin’s request, to cement an alliance between Khamenei and Putin and to lay the military groundwork for Russia’s intervention in Syria.

Iran’s Fars news agency reported that following an unprecedented meeting between Khamenei and Putin in Tehran in November that year, Soleimani was in Russia again the following month, where he “held a meeting with President Putin and high-ranking Russian military and security officials during a three-day visit [and] they discussed the latest developments in Syria, Iraq, Yemen and Lebanon.”

By the spring of 2019, Soleimani, the son of a poor farmer who had made good by doing so much harm, may have felt himself to be untouchable. Supremely confident, undeniably powerful and revered at home and among the many militant groups throughout the region that benefited from his lethal largesse, he had increasingly abandoned the low profile crucial for his trade, appearing frequently in official photographs released by a regime keen to exploit the aura of its star player.

On March 10, 2019, Soleimani received the ultimate accolade from his friend and mentor, Ayatollah Khamenei, when he became the first recipient since the revolution of Iran’s most prestigious medal, the Order of Zulfaqar.

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei awards Soleimani the rare Order of Zulfaqar on March 10, 2019. (AFP/khamenei.ir)

Soleimani became the first recipient of the Order of Zulfaqar, Iran’s highest military honor, since the Iranian revolution in 1979. (khamenei.ir)

Soleimani, said the Ayatollah, had “time and time again exposed his life to the invasion of the enemy and he has done so in the way of God, for God and purely for the sake of Allah. I hope that Allah the Exalted will reward and bless him, that He will help him live a blissful life and that He will make his end marked by martyrdom.”

Then Khamenei added: “Of course, not so soon. The Islamic Republic will be needing his services for many years to come.”

But by his own increasingly audacious actions, in Syria and Iraq, in Yemen and in the waters of the Gulf, Soleimani was ensuring that his journey to martyrdom would be measured not in years, but in months.

Deterring “the destabilizing and escalatory actions of the Iranian regime” is the number one priority of the US military’s Central Command. A mission statement setting out its priorities, updated since Soleimani’s death, offers a succinct summary of the Quds Force commander’s rush to martyrdom.

“Since May 2019, Iranian-supported groups in Iraq have attacked U.S. interests dozens of times and conducted scores of unmanned aerial system (UAS) reconnaissance flights near U.S. and Iraqi Security Force (ISF) bases,” it reads.

“The Iranian regime has attacked or seized foreign vessels in the Gulf, facilitated attacks by Houthi forces from Yemen into Saudi Arabia, continued to export lethal aid to destabilizing groups throughout the region, including those aiming to attack Israel, supported the Assad regime’s brutal conflict against its own people, and carried out an unprecedented cruise missile and UAS attack in September against Saudi oil facilities that destabilized international energy markets.”

Enough, in other words, was enough.

Frequently photographed together over the years, it was clear that Soleimani and Ayatollah Khameini were close. (Alamy)

Frequently photographed together over the years, it was clear that Soleimani and Ayatollah Khameini were close. (Alamy)

Hezbollah fighters march in Beirut on May 31, 2019, to mark Al-Quds (Jerusalem) International Day, founded by Ayatollah Khomeini. Iran has spent millions of dollars training, arming and funding Hezbollah. (AFP)

Hezbollah fighters march in Beirut on May 31, 2019, to mark Al-Quds (Jerusalem) International Day, founded by Ayatollah Khomeini. Iran has spent millions of dollars training, arming and funding Hezbollah. (AFP)

Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces chant before going into battle during the offensive to liberate Mosul from Daesh on Oct. 31, 2016, in Tal Al-Zaqaa, Iraq. (Getty Images)

Iraq’s Popular Mobilization Forces chant before going into battle during the offensive to liberate Mosul from Daesh on Oct. 31, 2016, in Tal Al-Zaqaa, Iraq. (Getty Images)

Newly recruited Houthi fighters chant slogans during a gathering in Yemen’s capital Sanaa to mobilize more fighters to fight pro-government forces on Jan. 3, 2017. (AFP)

Newly recruited Houthi fighters chant slogans during a gathering in Yemen’s capital Sanaa to mobilize more fighters to fight pro-government forces on Jan. 3, 2017. (AFP)

In August 2018, the guided-missile destroyer USS Jason Dunham intercepted a skiff en route to Yemen found to be carrying a shipment of illicit weapons from Iran. (Alamy)

In August 2018, the guided-missile destroyer USS Jason Dunham intercepted a skiff en route to Yemen found to be carrying a shipment of illicit weapons from Iran. (Alamy)

US sailors on board the USS Jason Dunham take an inventory of a large cache of AK-47 automatic rifles intercepted en route to Yemen in August 2018. (Alamy)

US sailors on board the USS Jason Dunham take an inventory of a large cache of AK-47 automatic rifles intercepted en route to Yemen in August 2018. (Alamy)

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei awards Soleimani the rare Order of Zulfaqar on March 10, 2019. (AFP/khamenei.ir)

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei awards Soleimani the rare Order of Zulfaqar on March 10, 2019. (AFP/khamenei.ir)

Soleimani became the first recipient of the Order of Zulfaqar, Iran’s highest military honor, since the Iranian revolution in 1979. (khamenei.ir)

Soleimani became the first recipient of the Order of Zulfaqar, Iran’s highest military honor, since the Iranian revolution in 1979. (khamenei.ir)

The head of the snake

In the dark of a January night in 2007, a convoy of vehicles slipped across the porous border between Iran and northern Iraq, bound for the Kurdish city of Erbil. Watching the convoy’s progress via surveillance feed was Gen. McChrystal, head of the US military’s secretive Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC), a hunter-killer unit whose business is the capture or extermination of high-value targets.

The convoy had attracted the JSOC’s attention because intelligence had red-flagged one of its passengers — Qassem Soleimani, the head of Iran’s elite Quds Force, an organization described later by McChrystal as “a combination of the CIA and JSOC in the United States.”

For a while that night, Soleimani was in the sights of the US military, and his life hung in the balance.

“There was good reason to eliminate Soleimani,” McChrystal wrote in his 2019 profile for Foreign Policy, published just weeks before the assassination of the man he described as “a deadly puppet master.”

“At the time,” he added, “Iranian-made roadside bombs built and deployed at his command were claiming the lives of U.S. troops across Iraq.”

There was no doubt that Soleimani and the Quds Force were behind much of the mayhem and that his journey to Erbil in January 2007 presaged a further wave of attacks but, for reasons that are never likely to be clear, McChrystal took his finger off the trigger that night. He “decided that we should monitor the caravan, not strike immediately,” but by the time the convoy had reached Erbil, “Soleimani had slipped away into the darkness.”

Soleimani, pictured meeting Syria’s President Bashar Al-Assad in Tehran on Feb. 25, 2019 with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, moved in the highest diplomatic circles. (AFP/Syrian Arab News Agency)

Death stalked Soleimani again the following year, according to an account given in January 2020 by a former CIA covert field-operations officer. Mike Baker, who now runs a security company and is a regular talking head on US TV shows, left the agency in the late 1990s after 15 years of service.

Speaking on the Joe Rogan Experience podcast two weeks after Soleimani’s killing in January, Baker said Soleimani and Imad Mughniyeh, the second-in-command of Iran-backed Hezbollah, had been targeted together by Israel in 2008.

“The Israelis had an opportunity to take out Mughniyeh and Soleimani, but they backed off, essentially because the US wouldn’t get behind the idea that we were going to take out Soleimani,” he said. “At that point, that was a step too far.”

Soleimani’s reprieve would last for 12 years, but Mughniyeh had only days to live. He was killed in Damascus on Feb. 12, 2008, when a bomb in his car exploded shortly after he left a reception held by Tehran’s ambassador to Syria to mark the 29th anniversary of the Iranian revolution.

On another occasion, in October 2019, Tehran claimed it had foiled an elaborate plot by “Arab-Israeli secret services” to kill Soleimani by detonating a massive bomb planted in a tunnel beneath a mosque built by his father in Kerman.

But time was running out for Soleimani.

On Dec. 27, 2019, a civilian US contractor died and several others were injured in a rocket strike on an Iraqi military base in Kirkuk carried out by Iranian proxy Kataib Hezbollah. Two days later, on Dec. 29, US F-15E Strike Eagle fighters bombed several Kataib Hezbollah bases in Iraq and Syria, killing some 25 militants. The airstrikes triggered protests in Baghdad, where on New Year’s Eve a large crowd, composed mainly of members of Kataib Hezbollah, tried to break into the US Embassy.

Tweeting that night, Trump accused Iran of having orchestrated the attack and said its government “will be held fully responsible.” Later he tweeted again, adding that Iran would “pay a very BIG PRICE. This is not a Warning, it is a Threat.”

Two days later the Department of Defense announced that, “at the direction of the President,” Soleimani had been killed.

Various accounts exist of Soleimani’s last hours on earth, each differing slightly in one or more details. All agree, however, that his story ended on a Baghdad airport access road, in a salvo of missiles unleashed from a US MQ-9 Reaper drone in the early hours of Friday, Jan. 3.

Soleimani, accompanied by two high-ranking IRGC intelligence officers and two bodyguards, had travelled to Iraq from Damascus on board a scheduled flight operated by the Syrian airline Cham Wings, which flies to a number of destinations throughout the Middle East, including Baghdad, Erbil, Kuwait and Tehran.

Although privately owned, Cham Wings has close links to the Syrian regime and the IRGC. Arab News was unable to contact anyone at Cham Wings for comment.

Some reports suggested the vehicles were armored, but whether or not they were would prove to be irrelevant.

In 2014, the airline was designated by the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control for having “materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services in support of, the Government of Syria and Syrian Arab Airlines,” which itself had been designated previously “for acting for or on behalf of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force.”

In a statement issued on Dec. 23, 2016, the US Treasury said Cham Wings had also “cooperated with Government of Syria officials to transport militants to Syria to fight on behalf of the Syrian regime and assisted the previously designated Syrian Military Intelligence (SMI) in moving weapons and equipment for the Syrian regime.”

Soleimani, in other words, had every reason to expect safe passage on board a Cham Wings flight.

On the night of Jan. 2, Flight 6Q501 from Damascus to Baghdad, scheduled to have taken off at 7:30 p.m. Damascus time, was delayed for about three hours — because of bad weather, according to some reports or, according to others, because Soleimani arrived late at the airport and the plane was going nowhere without him.

For security reasons, neither Soleimani nor his four companions were on the passenger manifest. When they did finally board the Airbus A320, they sat at the front of the aircraft, ready to disembark ahead of the other passengers after a flight that would take a little over one hour.

Flight 6Q501 landed in Baghdad at about 12:32 a.m. on Jan. 3.

According to officials at Baghdad International Airport cited by Reuters in a Jan. 9 report, Soleimani’s party “exited the plane on a staircase directly to the tarmac, bypassing customs” and made their way to two waiting vehicles — two Toyota SUVs, by some accounts, or a Hyundai Starex minibus and a Toyota Avalon sedan, according to others.

Some reports suggested the vehicles were armored, but whether or not they were would prove to be irrelevant. To some extent, armor can protect a vehicle’s occupants from roadside bombs, but is useless against the 45-kilogram laser-guided Hellfire missile, which hits its target at over 1,500 kilometers per hour and carries a 9-kilogram high-explosive warhead designed to destroy heavily armored tanks.

At the waiting vehicles, the Iranians were met by Al-Muhandis, founder of Kataib Hezbollah and deputy head of Iraq’s PMF, and four other members of the PMF, who had driven onto the airport through a cargo gate.

Soleimani in an undated photo with Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, who died alongside him in January 2020. (khamenei.ir)

All 10 men had only minutes left to live.

By all accounts, Soleimani and Al-Muhandis got into one of the two vehicles, and the four IRGC men boarded the other. The convoy drove back out through the cargo gate and onto an access road running alongside the airport perimeter wall. According to Reuters, two Hellfire missiles struck Soleimani’s car here at 12:55 a.m.; a second later, a third missile hit the vehicle carrying his security detail.

Watch the strike on Soleimani's convoy and its aftermath.

There is no doubting the capabilities of American surveillance technology, from its fleet of spy satellites, which can identify and photograph objects on Earth as small as 10 centimeters across, to its armada of drones, equipped with heat sensors and high-powered conventional and infrared cameras.

But whatever air or space-borne assets were focused on Soleimani’s arrival that night, it is clear that the strike would not have been contemplated without reliable human intelligence assets on the ground, in Baghdad and Damascus and, quite possibly, Iran — even, perhaps, within the ranks of the IRGC itself.

According to sources in Iraq’s security services, Baghdad airport employees, police officials and two employees of Syria’s Cham Wings Airline interviewed by reporters from Reuters’ Baghdad bureau in the hours and days after the attack, the investigation that was launched by Iraq’s security services within minutes of the strike “focused on how suspected informants inside the Damascus and Baghdad airports collaborated with the US military to help track and pinpoint Soleimani’s position.”

The US kill team would have needed to have had several such informants.

For a start, they would have needed to know that Soleimani was in Syria in the first place — perhaps not too difficult for a low-level asset connected to either the Syrian regime or the IRGC to determine. But they also would have needed advance notice of when he would be there, plus that he was planning to fly to Baghdad and when.

Soleimani’s schedule would have been a carefully guarded secret known only to a handful of close associates, but without advance knowledge of it the Americans could not have ensured that their assets at Baghdad airport were in place and ready to act. It seems logical to conclude that someone very close to the Quds Force commander must have betrayed him.

The burning remains of the car in which Soleimani died after the missile strike by a US drone in Baghdad on Jan. 3, 2020. (Fox News)

Some reports suggest that the MQ-9 Reaper that carried out the attack was launched from the Al-Udeid military base in Qatar and controlled remotely by a crew of two at Creech Air Force base in Nevada. In fact, with a range of only 1,850 kilometers, the drone — or up to three drones, according to some reports — must have come from a base nearer to Baghdad, which is a round trip of over 2,000 kilometers from Al-Udeid.

The prime candidate is the Al-Asad base in western Iraq, which is used by the Americans and is only about 180 kilometers from Baghdad. With a cruising speed of about 370 kilometers per hour, the Reaper would have reached Baghdad airport in about half an hour, and so need not have been launched until the strike team received confirmation that Soleimani’s aircraft had left Damascus for its hour-long flight to Baghdad.

Nevertheless, the Americans must have had substantial advance notice of Soleimani’s travel plans, and were not merely reacting to on-the-day observed intelligence — and again, this suggests that someone extremely close to Soleimani, rather than a mere informant at Damascus airport, may have betrayed him.

Confirmation that Soleimani had actually boarded the flight could have come either from an asset at Damascus airport capable of identifying him on sight — and able to get close enough to do so — or from a member of the Cham Wings flight crew. Equally important to the operation would have been the intelligence that the flight had actually taken off and at what time.

With the kill team armed with the initial intelligence that Soleimani’s aircraft was scheduled to arrive in Baghdad at about 9:30 p.m. local time, by the time the flight actually touched down three hours later, the drone would have been in the air for up to seven hours.

Given its endurance of about 14 hours, and allowing for an hour of fail-safe time for the return journey to Qatar, by the time of the attack the drone would have had little more than three hours of operational time left. This was enough but, as The New York Times reported on Jan. 11, “the plane was late and the kill team was worried … the hours ticked by and some involved in the operation wondered if it should be called off.”

But it was not called off.

In a statement issued just hours after the attack, the US Department of Defense said that “at the direction of the President, the U.S. military has taken decisive defensive action to protect U.S. personnel abroad by killing Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps-Quds Force, a U.S.-designated Foreign Terrorist Organization.”

Soleimani, it added, had been “actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region.” Furthermore, “General Soleimani and his Quds Force were responsible for the deaths of hundreds of American and coalition service members and the wounding of thousands more.

“He had orchestrated attacks on coalition bases in Iraq over the last several months — including the attack on December 27th — culminating in the death and wounding of additional American and Iraqi personnel. General Soleimani also approved the attacks on the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad that took place this week.”

US President Donald Trump talks about the strike on Soleimani at a press conference the next day.

Various reports describe how Iraq’s security services, infuriated that the Americans had carried out the attack without consulting or even forewarning Baghdad, swung quickly into action, sealing off the airport and rounding up potential collaborators who had been working the night shift. Airport security, ground crew and other employees were interviewed for hours and had their phones confiscated and scrutinized.

An unnamed security official told Reuters that “initial findings of the Baghdad investigation team suggest that the first tip on Soleimani came from Damascus airport … [and] the job of the Baghdad airport cell was to confirm the arrival of the target and details of his convoy.” Suspects included two security personnel at Baghdad airport and two Cham Wings employees, said to be “a spy at the Damascus airport and another one working on board the airplane.”

Similar investigations were said to have been launched in Damascus by Syrian intelligence.

In an analysis for the Atlantic Council on Jan. 3, Robert Czulda, a former visiting professor at Islamic Azad University in Iran, wrote that Iranian counterintelligence now had to find an answer to the question: “Who betrayed Soleimani? One of his aides? Or maybe someone from Hezbollah? Or maybe — and this also cannot be ruled out — the Iraqis helped the Americans to get rid of the Iranian general, who had ruled their own country for long.”

And, in the murky waters of Iran’s internal politics, was it possible that some in Tehran had come to fear that Soleimani was going too far in provoking the Americans under the unpredictable President Trump, and that thanks to his operations Iran was sliding inexorably toward an open war that it could not hope to win?

It seems highly unlikely that anyone connected with Cham Wings, or even staff at Damascus or Baghdad airports, would have taken the huge risk of betraying Soleimani to the Americans. With only a handful of potential suspects to choose from, it would not have taken long for the IRGC, the Syrian government or the pro-Iranian militias in Iraq to have identified the guilty parties and exacted revenge.

To date, however, no reports of any arrests — or killings — related to Soleimani’s death have emerged in Iraq or Syria which, given the reach of the IRGC in both countries, seems extraordinary.

Unsurprisingly in the age of social media, conspiracy theorists were quick to suggest that Soleimani might not have been killed in the attack. A direct hit from a Hellfire missile can tear a human body to pieces, leaving very few identifiable parts. However, photographs from the aftermath of the strike quickly circulated, including one showing a severed arm, with a large red-stoned silver ring visible on the third finger of the hand.

This, it was widely reported, identified the corpse as that of Soleimani, but the claim was problematic.

Photographs taken of Soleimani over the years show him wearing similar, but not identical, rings. Al-Muhandis, who was travelling with Soleimani when their vehicle was struck, had also been photographed wearing a similar ring. Such aqeeq, or agate, rings, have a religious significance for some Shiite Muslims, partly because of a belief that the Prophet Muhammad wore a carnelian aqeeq. They are also thought to protect the wearer from harm.

In an “exclusive” broadcast on Jan. 11, Fox News claimed that US special forces had been following Soleimani’s convoy as it left the airport and “were on the scene within a minute or two” of the missile strikes. There, they “performed a so-called ‘bomb damage assessment,’ taking pictures of the scene and confirming that the drone had picked out the right car — and that Soleimani was no more.”

Fox said it had obtained a number of photographs “from a member of the US government,” including some “which Fox News will not show … graphic, close-up views of Soleimani’s body, which is grossly disfigured and missing limbs.” One photograph it did show, partially edited to obscure graphic details, “shows Soleimani's body burning next to the car in which he was riding.”

Fox News was told that “U.S. forces dragged Soleimani's body away from the scene and extinguished the fire before formally identifying the Iranian general.” They took photographs of his possessions, which included books of poetry, cash and a phone, said to be too badly damaged for analysis. A pistol and an assault rifle were also found in the wreckage of his vehicle.

Some of Soleimani’s possessions, reportedly found by US special forces who were on the scene. His phone, too badly damaged to be analyzed, is visible at the top left. (Fox News)

The report did not make clear, however, how the US soldiers were able to positively identify Soleimani.

It was Sunday, Jan. 5 — two days after the missile strike — before the remains of both Soleimani and Al-Muhandis were flown to the southwestern Iranian city of Ahvaz.

There, Soleimani’s flag-draped casket was loaded onto the back of a truck and driven through streets packed with thousands of black-clad mourners, chanting “Death to America,” a call that was echoed by Iranian parliamentarians in a televised session the same day. After three days of national mourning, Soleimani was buried on Tuesday, Jan. 7, in the martyr’s cemetery of Kerman.

Mourners surround a truck carrying Soleimani’s coffin during a funeral procession in his hometown of Kerman on Jan. 7, 2020. (AFP)

Still, death trailed in his wake. Iranian TV reported that more than 50 people were killed and 200 injured in a crush at his funeral, attended by a vast crowd of many hundreds of thousands of mourners who converged on Kerman’s Azadi Square.

There, Hossein Salami, the head of Iran's Revolutionary Guards, told the mourners: “We will take revenge, a hard and definitive revenge … The martyr Qassem Soleimani is more dangerous to the enemy than Qassem Soleimani.”

The day before, Soleimani’s daughter Zeinab had appeared on television, issuing similar threats. “The families of American soldiers in West Asia, who have witnessed America’s cruel wars, in Syria, Iraq, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Yemen and Palestine,” she said, “will be spending their days waiting for news of the death of their children.”

In a rare public appearance during Soleimani’s funeral procession in Tehran on Jan. 6, 2020, his daughter Zeinab vowed her father’s death would be avenged. (AFP)

Similar vows of vengeance flowed thick and fast from Iran’s leadership. Speaking just hours after the attack, Brigadier General Mohammed Pakpour, commander of IRGC ground forces, said: “The US terrorists and their vassals must wait for a crushing response and severe revenge.”

Many observers feared that after the mounting tensions of the previous months the attack on Soleimani would tip the US and Iran into open conflict. On the day after Soleimani was killed, President Trump, responding to Tehran’s sabre-rattling, issued a series of tweets, threatening to hit “VERY FAST AND HARD” 52 sites in Iran, “at a very high level & important to Iran & the Iranian culture.”

But the widely anticipated “crushing response” from Iran never came. Instead, on Jan. 8, Tehran launched what could only be described as a merely symbolic attack on two US air bases in Iraq.

In what it called Operation Martyr Soleimani, the IRGC fired more than 20 ballistic missiles, most of which struck the Al-Asad air base in Iraq’s Anbar province. At the time, it seemed a miracle that no one was killed or even injured (although a month later the US military would claim that more than 100 personnel had subsequently been diagnosed with “traumatic brain injury”). But it soon became clear that the attacks had been little more than a carefully orchestrated exercise in Iranian face-saving.

It emerged that Tehran had warned the Iraqis of the impending attack almost eight hours before the first missiles struck, by which time US and Iraqi troops and aircraft at the bases were safely under cover and out of harm’s way. Shortly after, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif tweeted that Iran “did not seek escalation or war” and had “concluded” its retaliation.

Hours later, disaster struck — not in the form of the war that many had feared was imminent, but in the shooting down of a civilian airliner shortly after its takeoff from Tehran airport. All 176 people on board Ukraine International Airlines Flight 752, including 82 Iranian and 63 Canadian citizens, were killed.

Five days after Soleimani’s death, Iranian forces on high alert accidentally shot down a Ukrainian commercial flight that had taken off from Tehran, killing all 176 people on board. (AFP)

Three days passed before Tehran admitted that the flight had been mistaken for a hostile aircraft by an IRGC missile battery on high alert. Even in death, Soleimani had added to the tally of lives he had claimed while alive.

Soleimani, pictured meeting Syria’s President Bashar Al-Assad in Tehran on Feb. 25, 2019 with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, moved in the highest diplomatic circles. (AFP/Syrian Arab News Agency)

Soleimani, pictured meeting Syria’s President Bashar Al-Assad in Tehran on Feb. 25, 2019 with Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, moved in the highest diplomatic circles. (AFP/Syrian Arab News Agency)

Soleimani in an undated photo with Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, who died alongside him in January 2020. (khamenei.ir)

Soleimani in an undated photo with Kataib Hezbollah leader Abu Mahdi Al-Muhandis, who died alongside him in January 2020. (khamenei.ir)

The burning remains of the car in which Soleimani died after the missile strike by a US drone in Baghdad on Jan. 3, 2020. (Fox News)

The burning remains of the car in which Soleimani died after the missile strike by a US drone in Baghdad on Jan. 3, 2020. (Fox News)

Some of Soleimani’s possessions, reportedly found by US special forces who were on the scene. His phone, too badly damaged to be analyzed, is visible at the top left. (Fox News)

Some of Soleimani’s possessions, reportedly found by US special forces who were on the scene. His phone, too badly damaged to be analyzed, is visible at the top left. (Fox News)

Mourners surround a truck carrying Soleimani’s coffin during a funeral procession in his hometown of Kerman on Jan. 7, 2020. (AFP)

Mourners surround a truck carrying Soleimani’s coffin during a funeral procession in his hometown of Kerman on Jan. 7, 2020. (AFP)

In a rare public appearance during Soleimani’s funeral procession in Tehran on Jan. 6, 2020, his daughter Zeinab vowed her father’s death would be avenged. (AFP)

In a rare public appearance during Soleimani’s funeral procession in Tehran on Jan. 6, 2020, his daughter Zeinab vowed her father’s death would be avenged. (AFP)

Five days after Soleimani’s death, Iranian forces on high alert accidentally shot down a Ukrainian commercial flight that had taken off from Tehran, killing all 176 people on board. (AFP)

Five days after Soleimani’s death, Iranian forces on high alert accidentally shot down a Ukrainian commercial flight that had taken off from Tehran, killing all 176 people on board. (AFP)

After Soleimani

Soleimani is gone. But a year after his death, his legacy of murderous interference in the affairs of the region continues to haunt the final days of the Trump administration’s dealings with Iran and is poised to cast its shadow over US attempts to revive the nuclear deal after President-Elect Joe Biden’s inauguration on Jan. 20.

If, as Tehran believed, the killing of Soleimani was designed to provoke Iran into a disastrous war it could not hope to win, then the subsequent assassination of Iran’s top nuclear scientist on Friday, Nov. 27, was read by some as a last attempt by the Trump administration and its allies to provoke Iran and stymie Biden’s plan for the US to re-engage with the Iran nuclear deal.

The Biden camp has suggested repeatedly that it is likely to attempt to revive the nuclear deal, also called the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). One of the strongest signals that this would be the case was Biden’s appointment on Nov. 23 of Antony Blinken as his pick for secretary of state. Blinken, who was deputy secretary under the Obama administration, was a strong supporter of the nuclear deal and has defended it frequently since Trump abandoned it in May 2018.

Antony Blinken speaks after being introduced on Nov. 24, 2020, by US President-Elect Joe Biden as his nominee for secretary of state. (Getty Images)

In an interview with France 24 on May 20, 2019, Blinken described the escalating tensions in the region as “unfortunate, because we didn’t have to be where we are now. It was unfortunate that the United States pulled out of an agreement that Iran, for all the things that we don’t like that it does, was complying with.”

Yet there is evidence that the campaign of “maximum pressure” that Trump substituted for the nuclear deal has been working.

In October 2019, a poll carried out in Iran for the Center for International and Security Studies at Maryland found that three-quarters of Iranians “would approve of their government talking to the Trump administration in a multilateral forum” if the US returned to the JCPOA.

Furthermore, if it did, “a majority would also be open to broader negotiations covering Iran’s nuclear program, its ballistic missile development, its military activities in the Middle East, and all remaining sanctions on Iran.”

The policy of maximum pressure, said Sir John Jenkins, the former British ambassador to Iraq and Saudi Arabia, “was not designed to achieve the overthrow of the Islamic republic, which is of course where a lot of people start when they analyze this. It was designed to raise the cost to Tehran of its chronic adventurism and to increase the level of social tension within the country, which will then act as some sort of constraint upon the freedom of action, particularly of the IRGC, and to make it more expensive for Iran to do what it does in Iraq, Syria and Lebanon.”

For its part, it is clear that Tehran sees the transition from Trump to Biden as an opportunity and has already set out a series of preconditions for re-engaging with America over the nuclear deal.

“The United States must repent,” a spokesman for the Iranian foreign ministry said in November. “This means that it must firstly admit to its mistakes and secondly, stop the economic war against Iran. Thirdly, it must mend its ways and commit to its obligations and, as the fourth step, compensate [Iran] for losses.”

On Dec. 3, Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Zarif even put a price tag on the cost of US sanctions which, he said, had inflicted “$250 billion of damage on the Iranian people.”

But the prospect of the US agreeing to compensate Iran, said Sir John, was “politically inconceivable.”

Dr. Majid Rafizadeh, an Iranian-American political scientist and an expert on foreign policy in Iran and the US, believes it would be a serious mistake for the incoming Biden regime to row back on sanctions and to trust Iran to re-engage with the “flimsy” nuclear deal.

“The ‘maximum pressure’ campaign, despite its many detractors, was beginning to bear fruit, with Tehran finally feeling the economic need to pull back resources from its long-standing band of proxies,” he said.

“Since the Trump administration pulled out of the nuclear deal, Tehran’s oil exports have shrunk from nearly 2.5 million barrels per day to approximately 100,000 barrels. As a result, the ruling mullahs are facing one of the worst budget deficits in their four-decade history of being in power. Iran’s regime is currently running a $200 million budget deficit per week and it is estimated that if the pressure on Tehran continues, the deficit will hit roughly $10 billion by March 2021. This deficit will, in return, increase inflation and devalue the currency even further.”

The decrease in revenue “directly impacts Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps and its affiliates,” and as a result “Iran’s militia groups are receiving less funding to pursue their terror activities.”

It would, he added, be a grave mistake to think that the end of Soleimani meant the end of Iranian meddling: “The Iranian regime will continue to do whatever it can to pursue its hegemonic ambitions and military adventurism in the region.”

Certainly, the regime was quick to appoint Soleimani’s successor. Like Soleimani, Esmail Ghaani, 62, also served during the Iran-Iraq war, later joining the newly founded Quds Force. Hopes that Soleimani’s death will see the end of Iranian influence with its many proxy militant groups seem slim at best. Ghaani was sanctioned by the US Treasury in 2012 for having control of “financial disbursements” to proxies of the Quds Force.

Esmail Ghaani, the man who replaced Soleimani as commander of the Quds Force. (AFP/khameini.ir)

Regardless, a return to some form of nuclear deal now seems inevitable.

On Dec. 7, Jake Sullivan, Biden’s choice for national security adviser, said it was “feasible and achievable,” for the new administration to put Iran’s nuclear program “back in a box” by rejoining the deal, lifting sanctions and honoring America’s original commitment to the JCPOA. After that, he said, negotiations aimed at curtailing Iran’s interference in other countries could begin.

This, said Sir John, was where “the original JCPOA was flawed, because it didn’t address the wider issue of Iranian activities in the region, particularly in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, and its attempts over 40 years at subversion in the Gulf states.”

It was vital, he added, that any new nuclear deal addressed Iran’s “adventurism” — and that the Gulf states urgently make the case that it should.

Crucially, he said, “they need to be talking to the incoming administration, which is always difficult in a pre-inauguration period and has become even more so because Trump is still refusing to acknowledge that Biden has won.”

The normalization of relations between the UAE, Bahrain and Israel, he believes, with other states looking likely to follow suit, can only help.

“There is a case that they need to make to the Biden administration about why they are useful and important, and it is easier to make that case if they do it together rather than separately.

“They will all want to be consulted in the formation of a new US policy on Iran. They need to say, ‘If you consult us, we don’t necessarily need to be in the room when it happens, but we do need to be consulted on this because it’s in our vital interest, and we will help you’.”

Crucial to that interest, he believes, is “a separate policy of containment and deterrence against Iranian adventurism in the region — and that does imply the presence of US forces in the region.”

Any new deal, added Sir John, “also needs to address what has happened in terms of Iran’s enrichment of uranium since the Trump administration recused itself from the JCPOA.”

Tehran has, he added, “been very clever in the way they’ve done it. They are trying to calibrate their response, because they’ve got half an eye on Washington and half an eye on Brussels, and they have deliberately breached the limits set by the JCPOA but not in a way that would make everybody think they have conclusively turned their backs on it.”

Under the deal, Iran was allowed to enrich uranium up to a concentration of only 3.67 percent, but since the US pulled out it has been enriching to 4.5 percent, enough to power its Bushehr power plant. In July 2019, Tehran also announced it would also breach limits on stockpiles of enriched uranium and heavy water set out in the JCPOA and on Jan. 5, 2020 — two days after Soleimani’s death — it rejected the limits placed by the deal on the number of centrifuges it could operate.

At each stage, Iran has said it would continue to cooperate with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and would return to the terms of the deal if the US lifted sanctions, but it has been sailing close to the wind.

US President Donald Trump holds up a document reinstating sanctions against Iran after announcing the US withdrawal from the nuclear deal on May 8, 2018. (AFP)

On Nov. 16, The New York Times reported that four days earlier, following a report from the IAEA that Iran’s uranium stockpile was now 12 times larger than had been permitted under the JCPOA, the US president had asked senior advisors to come up with options for attacking the country’s nuclear facility at Natanz.

Trump asked senior advisors to come up with options for attacking the country’s nuclear facility at Natanz, 270 kilometers south of Tehran. (AFP)

According to unnamed sources, Trump was talked out of a military response for fear that a strike “could easily escalate into a broader conflict in the last weeks of Mr. Trump’s presidency.”

However, officials told the Times, Trump “might still be looking at ways to strike Iranian assets and allies, including militias in Iraq” — and, 10 days later, nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh, a brigadier general in the IRGC, was gunned down just outside Tehran.

Iran’s top nuclear scientist Mohsen Fakhrizadeh was assassinated in an attack on his car outside Tehran on Nov. 27, 2020. (AFP/khameini.ir)

The coffin of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh during his funeral procession in the northeastern city of Mashhad. (AFP/Iranian Defence Ministry)

Despite the predictable bluster and talk of revenge after the killing of Soleimani, Tehran did not immediately react. Under normal circumstances, the audacious daylight killing of Fakhrizadeh on a busy road near the capital might also have been expected to provoke a retaliatory outrage but again Tehran has kept its finger off the trigger.

First, of course, came the mandatory threats of revenge. “All enemies of Iran should know well that the Iranian nation and the country’s authorities are more courageous and zealous than to let this criminal act go unanswered,” state news agency IRNA quoted Iranian President Hassan Rouhani as saying on Nov. 28. “The relevant authorities will respond to this crime at the proper time.”

Hardliners are snapping at the heels of Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, with a presidential election to be held in June 2021. (Getty Images)

But, Rouhani added, “the Iranian nation is wiser and smarter than to fall in the trap of the Zionists. They are after chaos and sedition. They should understand that we know their plans and they will not achieve their ominous goals.”

Tehran believes that Israel was behind the killing of the scientist, and not without good reason — the Israelis have form. Between 2010 and 2012, suspected Israeli agents killed four nuclear scientists on the streets of Iran, three in bombings and a fourth gunned down outside his home. Speculation now is that, with only a short amount of time before Trump is due to leave the White House, Israel, almost certainly with Washington’s blessing, hoped to provoke Iran into a response that would either justify an attack by the outgoing US administration, or would at the very least make it more difficult for Biden to revisit the nuclear deal.