MISSOURI, US: A good many Kurds in Turkey and elsewhere will be celebrating the departure of US President Donald Trump when he leaves office on Jan. 20.

Those in Iraq will remember when his administration hung them out to dry during their Sept. 2017 independence referendum, allowing Iran, Baghdad and Shiite militias to launch punitive attacks, while Turkey threatened to blockade them.

Turkey, meanwhile, had little reason to fear American outcry over its human rights violations as it arrested and jailed thousands of pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP) activists and their elected representatives.

And in case this did not prove sufficiently disappointing for the Kurds, Trump withdrew US troops from the Turkish border in northeastern Syria in October 2019, giving Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan the green light to invade the Kurdish enclaves there and ethnically cleanse hundreds of thousands from the area.

Kurdish forces in Syria, who had just concluded the successful ground campaign against Daesh, found themselves betrayed by a callous and unpredictable American administration. Just days before Trump greenlit the Turkish operation in a phone call with Erdogan, the Americans had convinced the Syrian Kurds to remove their fortifications near the Turkish border to “reassure Turkey.”

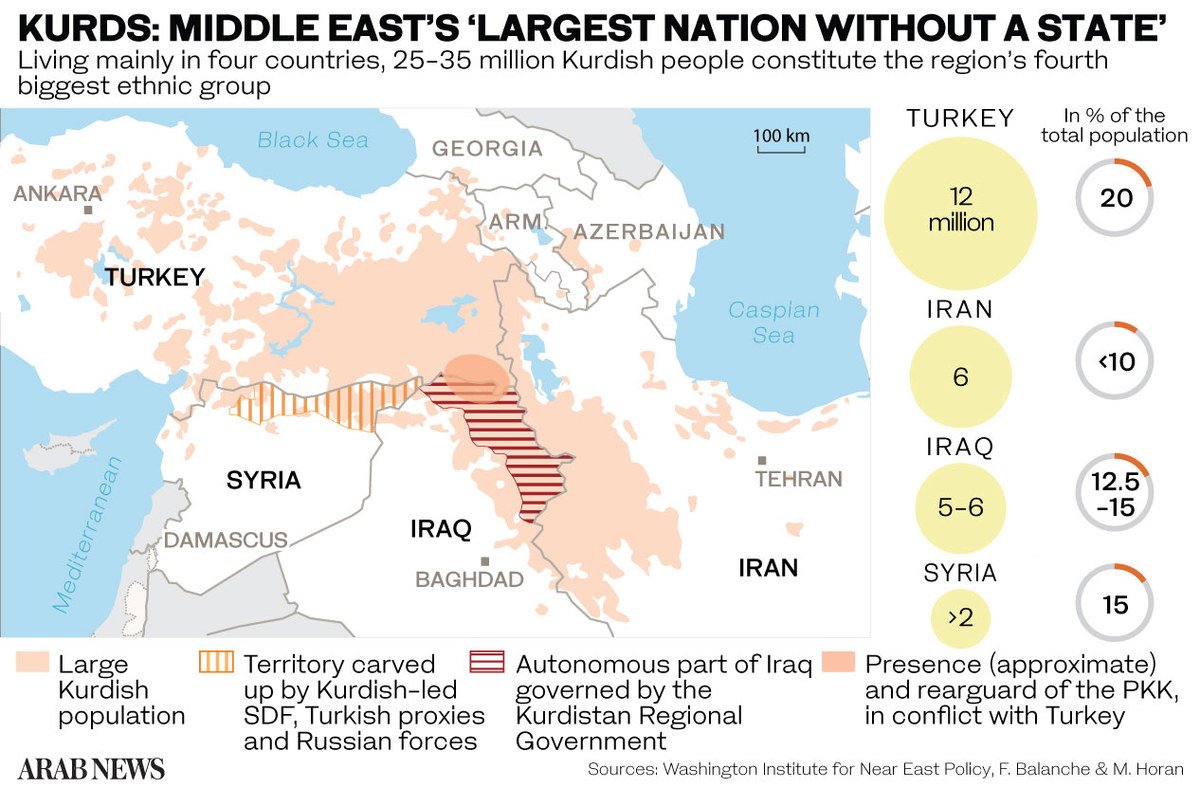

Most Kurds therefore look forward to President-elect Joe Biden taking over in Washington. In Turkey, from which roughly half the world’s Kurdish population hails, many hope the new Biden administration will pressure Ankara to cease its military campaigns and return to the negotiating table with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

In this April 28, 2016 photo, then US Vice President Joe Biden talks to Iraqi Kurdish leader Massud Barzani (R) during his visit to the capital of the Kurdish autonomous region in northern Iraq. Turkish Kurds are hoping to get help from the US, now that Biden has been elected president. (AFP file photo)

At the very least, they hope a Biden-led administration will not remain silent as Erdogan’s government tramples upon human rights in Turkey and launches military strikes against Kurds in Syria and Iraq as well.

Judging by the record of the Obama administration, in which Biden served as vice-president, Kurds may expect some improvements over Trump. But they should also not raise their hopes too high.

One need only recall how Erdogan’s government abandoned the Kurdish peace process in 2015, when the Obama administration was still in power. At that time, the HDP’s improved electoral showing in the summer of 2015 cost Erdogan his majority in parliament. He responded by making sure no government could be formed following the June election, allowing him to call a redo election for November.

Between June and November, his government abandoned talks with the Kurds and resumed the war against the PKK. The resulting “rally around the flag” effect saw Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP) improve its showing in November, boosted further by the Turkish army siege of entire Kurdish cities, which in effect disenfranchised them.

Following the November 2015 vote, Erdogan formed a new government with the far-right and virulently anti-Kurdish National Action Party (MHP).

The militarization of Ankara’s approach to its “Kurdish problem” increased even further under the AKP-MHP partnership. In 2015 and 2016, whole city blocks in majority Kurdish cities of southeastern Turkey were razed to the ground as part of the counterinsurgency campaign. In the town of Cizre, the army burned Kurdish civilians alive while they hid in a basement.

Mourners lower into a grave the coffin of Kurdish leader Mehmet Tekin, 38, who was killed at his home in Cizre by Turkish troops, during his funeral in Sirnak on December 23, 2015. (AFP file photo)

In Sirnak, footage emerged of Turkish forces dragging the body of a well-known Kurdish filmmaker behind their armored vehicle. In Nusaybin, MHP parliamentarians called for the razing of the entire city.

Urban warfare is never pretty, of course, and the PKK held part of the blame for the destruction as a result of its new urban warfare strategy. Many aspects of the Erdogan government’s counterinsurgency actions of 2015 and 2016 went beyond the pale, however, and should have earned at least some rebukes from Washington.

The Obama administration stayed largely silent during this time. Policy makers in Washington had finally gained Turkish acquiescence to use NATO air bases in Turkey in their campaign against Daesh and Ankara has also promised to join the effort.

What Obama really received from Ankara, however, were a few token Turkish airstrikes of little significance against Daesh and a rising crescendo of heavy attacks against America’s Kurdish allies in Syria.

Erdogan’s government duly reported every cross-border strike and various incursions and invasions into Syria as “operations against terrorist organizations in Syria” — conveniently conflating Daesh and the Syrian Kurdish forces.

Turkey even employed former Daesh fighters and other Syrian radical groups among its proxy mercenaries in these operations, further aggravating Syria’s problems with militant Islamists.

INNUMBERS

- 87 Media workers detained or imprisoned for terrorism offenses.

- 8,500 People detained or convicted for alleged PKK ties.

The quid pro quo of this arrangement involved Washington turning a blind eye to Turkey’s human rights abuses against Kurds both in Syria and Turkey. Even Turkish airstrikes in Iraq, which at times killed Iraqi army personnel and civilians in places like Sinjar, failed to elicit any American rebukes — under Obama or Trump.

If the new Biden administration returns to the standard operating procedures of the Obama administration regarding Turkey, little may change.

Although a Biden administration would probably not callously throw erstwhile Kurdish allies in Syria or Iraq under the bus as Trump did, they might well continue to cling to false hopes of relying on Turkey to help contain radical Islamists.

Many in Washington even think Turkey can still help the US counter Russia and Iran — never mind the mountain of evidence that Turkey works with both countries to pursue an anti-American agenda in the region.

Alternatively, Biden may prove markedly different to his incarnation as vice president. Biden knows the region well, has called Erdogan an autocrat on more than one occasion and has repeatedly shown sympathy for the Kurds and their plight in the past.

In charge of his own administration rather than acting as an aide to Obama’s, Biden could conceivably break new ground regarding Turkey and the Kurds.

If so, he might start by pressuring Turkey to abide by human rights norms. Selahattin Demirtas, the former HDP leader and 2018 Turkish presidential hopeful, as well as tens of thousands of other political dissidents have been languishing in pre-trial detention in Turkey for years now.

In this October 8, 2020 photo, a woman and her child are seen at the Washukanni refugee camp near the town of Tuwaynah, west of Syria's northeastern city of Hasakah. The are among tens of thousands whose homes and belonging have been seized or looted since the Turkish offensive in October 2019. (AFP file photo)

In December 2020, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that Demirtas’ detention is politically motivated and based on trumped-up charges and that he must be released.

Although Turkey is a signatory to the court, it has repeatedly ignored such rulings. A more human rights-oriented administration in Washington might join the likes of France and others in pressuring Ankara on such matters.

A determined Biden administration might also try to coax or pressure Ankara back to the negotiating table with the PKK. A return to even indirect negotiations, especially if overseen by the Americans, could go a long way towards improving things in both Turkey and Syria.

Little more than five years ago, Turkey’s southeast was quiet and Syrian Kurdish leaders were meeting as well as cooperating with Turkish officials.

Turkish ruler Recep Tayyip Erdogan. (AFP)

If Erdogan and his MHP partners nonetheless remain adamant in maintaining their internal and external wars, then Biden should look elsewhere for American partners.

Biden said as much only last year, expressing his concern about Erdogan’s policies. “What I think we should be doing is taking a very different approach to him now, making it clear that we support opposition leadership ... . He (Erdogan) has to pay a price,” Biden said.

Washington should embolden Turkish opposition leaders “to be able to take on and defeat Erdogan. Not by a coup, not by a coup, but by the electoral process,” he added.

This kind of language from the new Biden administration might go a long way towards changing the current policy calculus in Ankara.

____________________

• David Romano is Thomas G. Strong Professor of Middle East Politics at Missouri State University