AI: Artificial intelligence or augmented inequality?

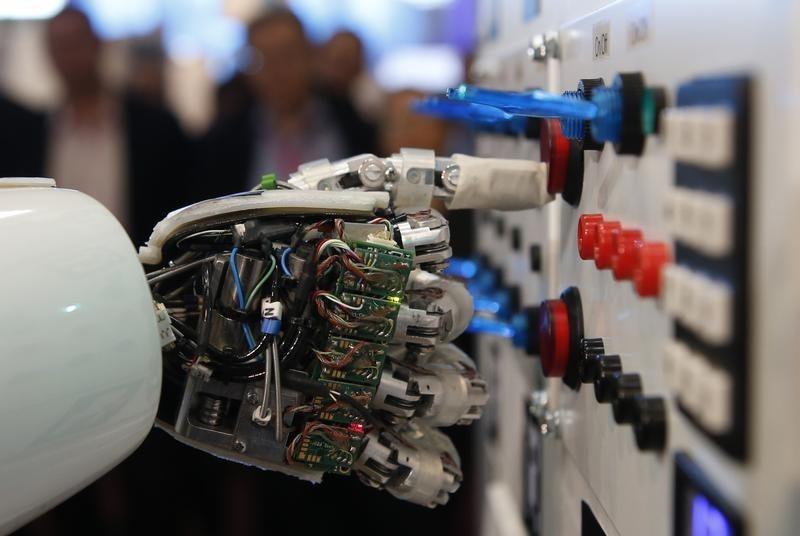

There is little doubt about the benefits of the current rush toward the new technologies that are rapidly transforming our companies, industries and, indeed, ways of living across the globe: Augmented reality, virtual reality, automation, bio-engineering, industry 4.0 and artificial intelligence.

Companies around the world, irrespective of the country or the industry in which they operate, are adapting or at least preparing to adapt to these innovations, if not enthusiastically then at least by compulsion, as they fear being left far behind in this latest race toward a new pot of gold at the end of the rainbow.

Though it is still early days, as many of the technologies are at the stage of initial development or in trial phases, some effects of the revolution are already being felt, most of them positive — for now. The business models of practically all of the unicorns (start-up companies with valuations of at least a billion dollars) are based on new technology. The valuations of several have reached sky-high levels even though they continue to bleed hundreds of millions of dollars each year as they pursue the perfection of their businesses in an attempt to arrest the losses.

In many cases, the valuations of these loss-making unicorns exceed those of well-known, established companies with consistent profitability and strong balance sheets based on proven business models. Yet, the lower valuations of these companies make it more expensive for them to raise capital. Hence, even traditional companies feel obliged to adopt new technologies or adapt their businesses accordingly.

One gain that they all can see and are excited about is cutting payrolls as robots, machines and computers take over many of the tasks currently performed by humans. Deploying fewer workers to produce the same, or even higher, output has been the trend for decades, but this process will gain momentum and spread to sectors so far left untouched, and to businesses that had emerged from the previous round of automation, such as those in information technology or the financial sector.

It might be a little early to assess the impact of job losses caused by the current revolution but the effects of previous phases of job losses in developed countries are there for all to see.

Ranvir S. Nayar

If we consider the state of development of AI and other technologies, the global impact within the next decade or so is expected to be surprisingly large. A study by consultancy firm McKinsey found that automation will lead to 400-800 million job losses worldwide by 2030, chipping away at nearly a third of the global workforce. Another study, by US research group Brookings Institution, predicts an even grimmer future, with job losses in the global workforce topping 38 percent.

The robotization of the workplace is certainly a huge plus for any business, as it immediately boosts profitability, meaning higher wages and benefits for CEOs and better returns for shareholders. Of course, in this zero-sum game the workers displaced by robots are the losers as many of them, perhaps most of them, will struggle to find another equivalent job.

It might be a little early to assess the impact of job losses caused by the current revolution but the effects of previous phases of job losses, especially in key sectors such as textiles, steel, mining and the automotive industry, in developed countries are there for all to see.

It is these displaced blue-collar workers from the mining, steel and car industries in the US that propelled Donald Trump to his rather surprising electoral victory in 2016. It is this section of the population across the EU that has led to the sharp rise in support for populist parties, some of whom now govern in countries such as Italy, Austria or the Netherlands, and are serious players in almost all other European nations.

If the scenario is cause for despair in the developed world, it is nothing short of catastrophic in developing countries. Many Western countries have already reached a comfortable standard of living, with reasonably good social-security systems for populations that are broadly declining, hence reducing the number of citizens that might be left behind in the race to automation.

In developing countries, however, almost all of the parameters are just the opposite. Populations are rising in most, which means more people are joining the workforce. A large number of people are already unemployed and their numbers, as a percentage of total population, are broadly rising. India, for instance, recently recorded its highest rate of unemployment in the past five decades, according to data from a leaked employment report prepared for the government.

The concept of a social security “net” is practically unheard of in such countries, where governments struggle to balance budgets and the standard of living is already undignified for many. Access to health care, education, clean drinking water on tap, a decent house and clean air is still extremely limited, and even when such things are available they are often of dubious quality.

Certainly, there are sections of the populations in the developing world who are better off now than they were before. And of course the group at the top of the pyramid is growing, both in numbers and in wealth. But the gap between those at the top and the bottom has been widening, in the developed and developing world alike, and especially in large countries such as the US and India. A report published in January by Oxfam, a British charity, stated that while the cumulative wealth of the world’s billionaires grew by $2.5 billion every day in 2018, more than 50 percent of the global population have to live on less than $5.50 a day. The 26 richest people in the world have the same cumulative wealth as 3.8 billion of the poorest.

The same report stated that 1 percent of India’s population owns 73 percent of the country’s wealth, which represents a sharp rise from the previous year. This growing gap is what should set the alarm bells ringing in the government and Indian society at large. It clearly indicates that the economic boom and modernization has hurt rather than helped the vast majority of people. Oxfam notes that between 2006 and 2015 — when India recorded its highest-ever economic growth, averaging more than 9 percent a year — the wages of ordinary workers increased by only 2 percent a year, while the wealth of billionaires grew six times faster.

If this is the situation before the full impact of robotization is felt, then the scenario in 2030, as predicted by the McKinsey report, should send shivers down the spines of global political leaders. They can no longer watch from the sidelines but need to take a more proactive role in planning for the future of the workforce.

- Ranvir S. Nayar is managing editor of Media India Group, a global platform based in Europe and India, which encompasses publishing, communication and consultation services.