China’s Belt and Road Initiative embraces the Middle East

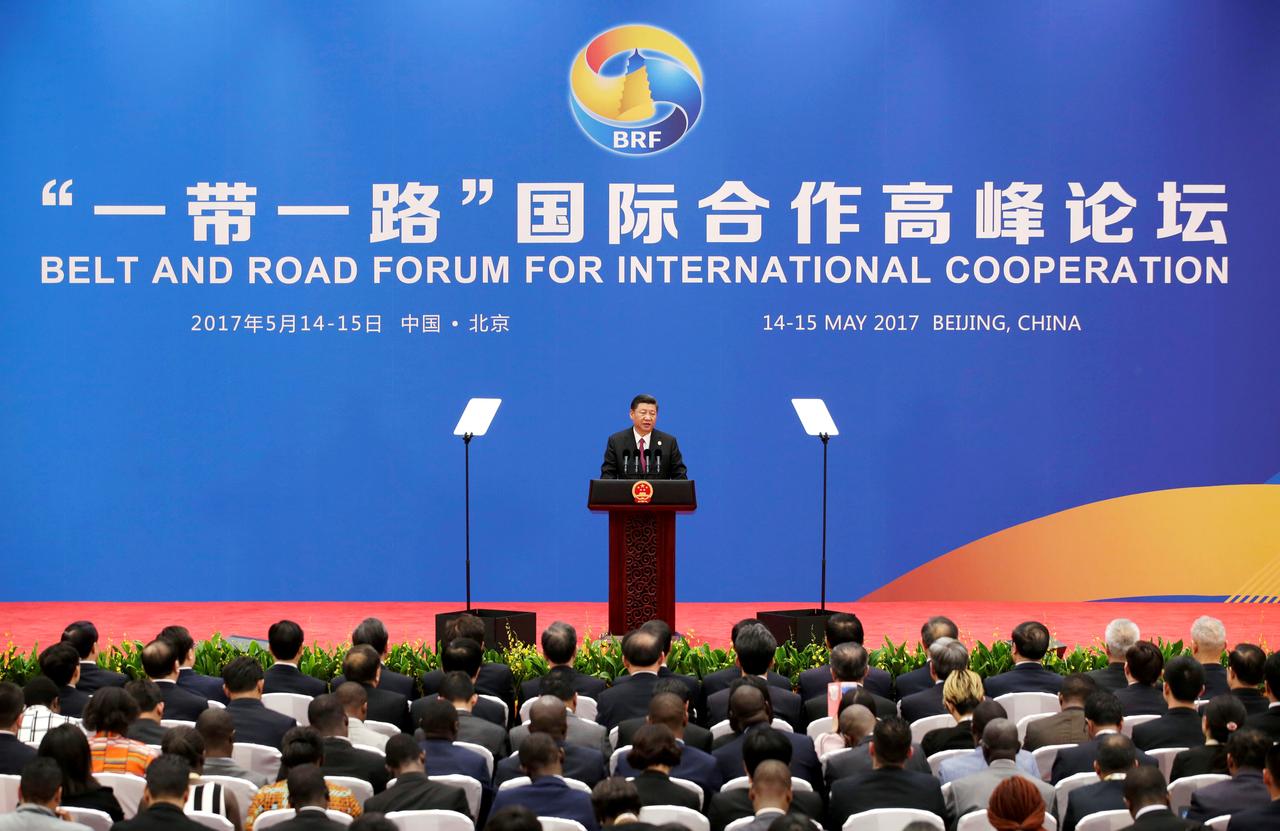

Chinese President Xi Jinping made two landmark speeches in 2013 — the first in Astana in September and the other in Jakarta a month later — in which he set out the contours of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a vision of transnational connectivity across Eurasia and the Indian Ocean. Its road, railway, energy, maritime and digital linkages will support industrial clusters and free-trade zones, lubricated by customs facilitation arrangements. It will cost between $4 trillion and $8 trillion and include more than 70 countries.

This will be a “space of deep economic integration” based on economic policy coordination and strong people-to-people ties. The BRI is accorded the highest priority in China: Banks and financial institutions have been set up to fund projects and, in October 2017, it was included in the constitution of the Chinese Communist Party.

The BRI has two parts. The belt is the land-based connectivity that envisages three links: One route goes from east China to Europe via Central Asia and Russia, another other goes from China to the Gulf and the Mediterranean, and the north-south route goes from southwest China across the Indochina peninsula to the Indian Ocean.

The road consists of three maritime linkages consisting of ports and sea lanes supporting industrial and energy projects in their hinterland. One link will go from China across the Indian Ocean to the African coast and then to the Mediterranean; another will go from China to the South Pacific Ocean; and, finally, the “Polar Silk Road” will in stages cross the Bering Strait, the Northern Sea Route, the transpolar corridor and later the Northwest Passage.

In the early period of the initiative, while the Eurasian land routes included Iran and Turkey, there were no details regarding the participation of Gulf and other Middle Eastern countries, possibly due to the prevailing confrontations and conflict. This has now changed, as China and the countries in the region recognize that the BRI will bring considerable value to both sides.

Energy is the most important long-term driver of ties between China and the Gulf. China, the world’s largest oil importer, gets 50 percent of its imports from this region, which has 30 percent of global reserves. As China’s demand for oil will continue to increase in the coming years, its dependence on the Gulf could reach 70 percent.

Energy is the most important long-term driver of ties between China and the Gulf.

Talmiz Ahmad

Beyond energy, China also has substantial trade ties with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states. Between 2000 and 2017, China-GCC bilateral trade went from $10 billion to $150 billion per year. Chinese investments in the Gulf stood at $60 billion in 2017, while its currency, the renminbi, is being increasingly accepted in commercial transactions. China is today seen as a valuable partner by all the GCC countries for the success of their “Vision” programs, to which the development of modern infrastructure and economic diversification are crucial factors.

In concrete terms, some GCC countries will be part of the recently announced “Industrial Park-Port Interconnection” projects. These will involve the development of industrial parks in Oman, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, which will be linked with newly developed ports — Duqm in Oman, Khalifa Port in Abu Dhabi, and Jazan on the Red Sea in Saudi Arabia.

GCC countries can also finance regional infrastructure projects, while their companies can execute road and port projects as contractors. In this way, the Middle East will emerge as an integrated energy, manufacturing, trade and investments center embracing West, South and Central Asia.

But this vision faces two challenges — one conceptual, the other regional. While China strongly protests that BRI is entirely a geoeconomic concept, many countries see in the initiative a Chinese geopolitical plan to create dependencies among participating countries and, over time, shape a new China-led global order to replace the West-led order.

This concern has led countries whose participation is crucial to realizing global connectivity — such as India, some Southeast Asian countries and some EU members — to oppose the initiative. They need to be assured that China, despite its emphasis on partnerships and “win-win” for mutual benefit, is not seeking to replace US hegemony with hegemonic intentions of its own.

This can be best achieved through China projecting the BRI not as a China-centric and China-led proposal, but as a truly international enterprise founded on consultation, transparency in all aspects, the upholding of norms of feasibility and accountability in all transactions, and independent redressal and dispute resolution mechanisms based on standard international norms.

Regional concerns relate to the security scenario in the Middle East. So long as the region remains deeply divided, with nations perceiving “existential” threats from their neighbors, there can be no possibility of it contributing usefully to the initiative.

Given the central importance of regional stability and the absence of an effective peace process, it is urgent that the countries most affected by this turmoil and uncertainty — such as India, Japan and China — join hands to shape a peace initiative to encourage engagement between estranged neighbors and, over time, promote region-wide peace and stability. Only then will the Middle East become a valued partner in the BRI and only then will the BRI vision provide the peace, growth and prosperity that Eurasia and the Indian Ocean so desperately need.

- Talmiz Ahmad is an author and former Indian ambassador to Saudi Arabia, Oman and the UAE. He holds the Ram Sathe Chair for International Studies, Symbiosis International University, Pune, India.